Well, when Mitgang’s book appeared, it gave the clam culture reason to think of itself as far sexier than the chicken culture. One might expect that the animosity would, as a result, have disappeared, but any good psychohistorian would be quick to point out that things are rarely as simple as that. The anti-chicken attitude in Babbington mighteventually have disappeared if Seafood and Sex hadn’t brought so many outsiders into the town. These newcomers, remember, had been attracted to Babbington by Mitgang’s descriptions of the clamming culture, so they arrived eager to embrace this culture, to penetrate its mysteries, to become part of it. (I’m told that it wasn’t unusual during this time to see half a dozen new Babbingtonians dogging the steps of a native, trying to learn to walk like a clamdigger ashore.) Sadly, among the aspects of clam culture embraced by the newcomers was the anti-chicken-farming prejudice.

Now here comes the strange irony of all this, the truth-is-stranger-than-fiction part. Most of the land available in Babbington for building the houses that the newcomers would live in was in the northern half of town, away from the bay, the part of town to which the chicken farmers had been driven so long ago. This part of town had come to be known as Babbington Heights. As newcomers moved into Babbington, the chicken farms gave way to tracts of new houses, one very much like another, and most of the chicken farmers collected their money from the developers and went off to the Midwest. The people who moved into the tract houses, lured by the promise of seafood and sex, tried to emulate the Old Babbingtonians but found that the real Old Babbingtonians treated them as if they’d been born and bred in the Heights, as if they’d sprung from generations of chicken farmers.

When my parents finally saved enough money to buy a small house, they moved from my grandparents’ house on No Bridge Road, not far from the heart of Old Babbington, to one of the small houses built on a former chicken farm in the Heights.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the people in the Heights, stung by the rejection of the Old Babbingtonians, should band together and reject the people who rejected them. That is what they did. They turned against the old clam-based culture and developed a nostalgic affection for chicken farming, for a past and a way of life that they had never known. Like most converts, they quickly became zealots. Within a year or two, there was hardly a household in the Heights that didn’t have its small flock in a little homemade coop out in the back yard. Most people kept laying hens, but some specialized in roasters or fryers, one or two kept fighting cocks, and several had flocks of homing chickens, which they would allow to walk around the block a few times in the gathering dusk of a summer evening, summoning them home with elaborate whistle signals when night fell. I admired the ability of the whistlers, and my father became one of the best of them, but I never cared for those chickens. I was friendly with the boys and girls in my neighborhood, but my roots were in the other culture—the bay owned my heart and my imagination.

FIFTH-GRADERS are not noted for their tolerance. When the population growth forced the town to build a new central upper elementary school, and boys and girls from all over Babbington were thrown together in that new central upper elementary school, they quickly took sides, as if they were choosing up for a mammoth game of dodgeball. I had grown up with a foot in each of the cultures; I tried to remain aloof from this tribalism, but it didn’t take long for me to see that—at least for the time being—I couldn’t. I could see the way it was going to be. If I was going to have any friends in school, I was going to have to choose one camp or the other. Veronica certainly saw that this was the case, and she began to grow impatient with my reluctance to choose. Finally, on the day when the winner of the name-that-school contest was announced, just a few minutes before the announcement itself, Veronica put her ultimatum to me, in terms nearly identical to those that Albertine was to use thirty years later. She touched her hand to my cheek and said, “Peter, you’ve got to choose: chicken or clams.” I chose clams, and Veronica chose chicken, and away she went.

YOU SEE HOW DIFFICULT it would have been for me to change that outcome without changing Babbington, my past, my feelings for my family, and so on. However, all of the foregoing seemed to me far too complex to include in the story of a childhood romance.

What to do? The solution that you’ll find in the pages that follow was not the only possible one, but working it out gave me great satisfaction. I compressed everything. Since Mitgang and Seafood and Sex were to blame for my losing Veronica, I cast Stretch Mitgang in Frankie Paretti’s role, and I used sex instead of societal forces as the reason for my losing Veronica. Then, since I really hated to see myself lose, whatever the reason, I had myself drop out of the contest instead. And finally, since my loss to Frankie Paretti still stung a bit after all these years, I cast him as an especially unattractive infant. That the satisfaction I gained from doing this to Frankie was ignoble bothered me only a little, and only for a little while.

Peter Leroy

Small’s Island

June 15, 1984

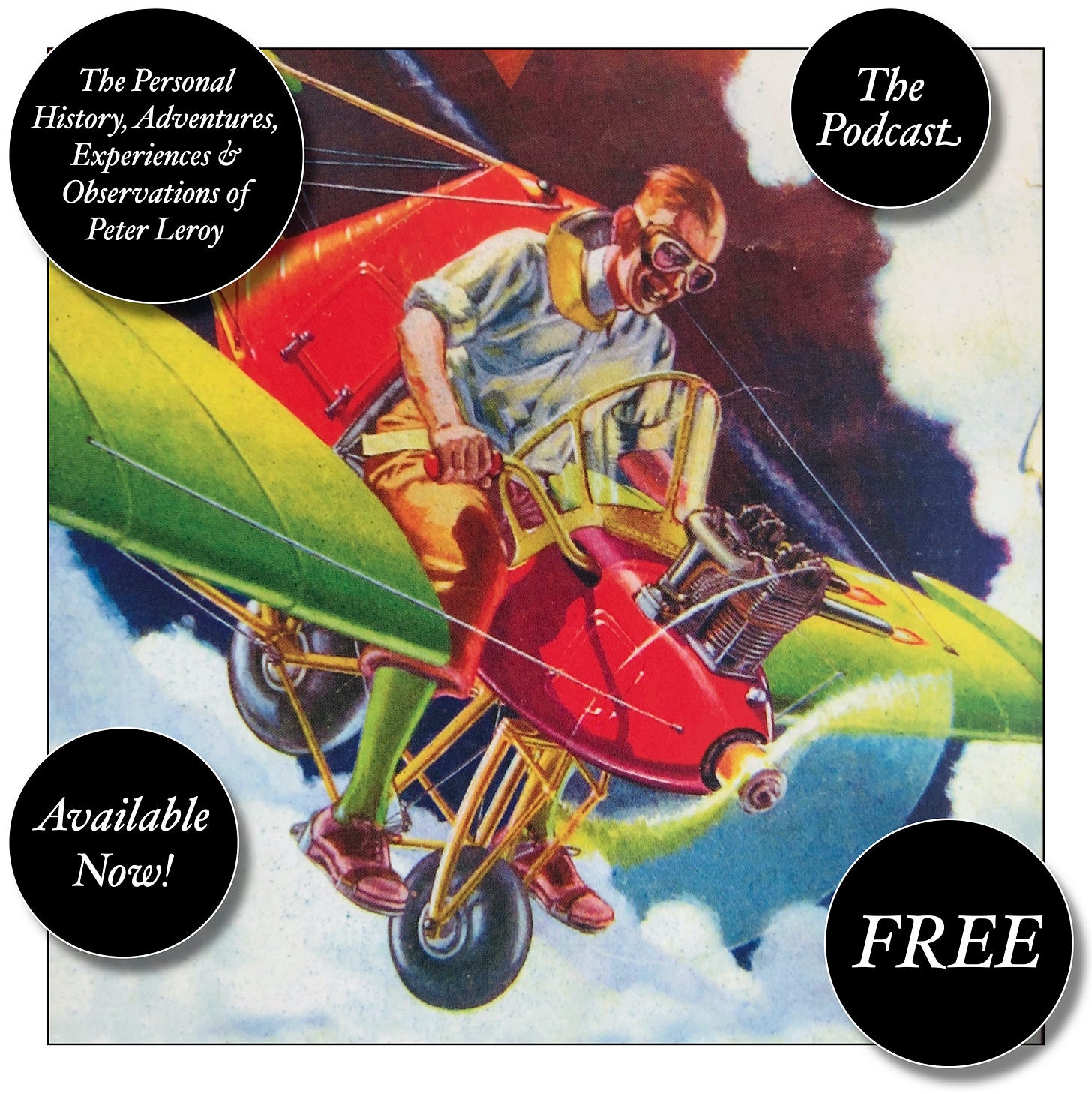

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” and “Call Me Larry,” the first eight novellas in Little Follies.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.

Share this post