2

I WAS ENCHANTED by that first Larry Peters adventure, The Shapely Brunette, from the moment I opened the book. On the front endpaper was a map of the area where Larry lived, a seacoast town called Murky Bay. The town of Murky Bay was situated on the shore of the bay called Murky Bay, and in Murky Bay were hundreds of islands, among them one called Kittiwake Island, where the Peters family lived. On the back endpaper was a map of the island itself and the floor plans of the Peters house and the workshops where Mr. Peters and the employees of Peters’s Knickknacks worked in secrecy to develop the gewgaws, trinkets, baubles, bric-a-brac, curios, gimcrackery, and brummagems that were the Peterses’ bread and butter. I spent quite some time with the maps and floor plans before I began reading the book, and I returned to them often while I was reading it. There was something about those maps and floor plans that invited the mind to wander, to meander among the islets as one might in a rowboat, to prowl around the house looking for hidden nooks, to imagine the conversations one might have with a companion while meandering among the islets or hiding in a nook. The maps and floor plans were detailed enough to seem to depict real places, and yet they were vague enough not to impose on me the limitations of reality, since I knew that they didn’t depict real places. They permitted—even invited—the fabrication of imaginary details, and if one accepted the invitation, as I did, reality did not intrude with the stern demands it made from day to day: the invented details had only to fit the empty spaces provided for them and be in keeping with the details that were already there; they did not have to be verifiable. Often, later, while I was rereading one Larry Peters adventure or another, the stories themselves seemed too specific; at such times, I found myself returning to the endpapers, and I began making up new stories for myself. Surely, I thought, these schematics were deliberately designed to encourage this kind of dreaming, and surely the stories were intended only to give one an excuse for sitting still for long hours, imagining new goings-on on Kittiwake Island, imagining the voices across the Peterses’ dinner table, the debates that must have taken place in the knickknack workrooms, and so on.

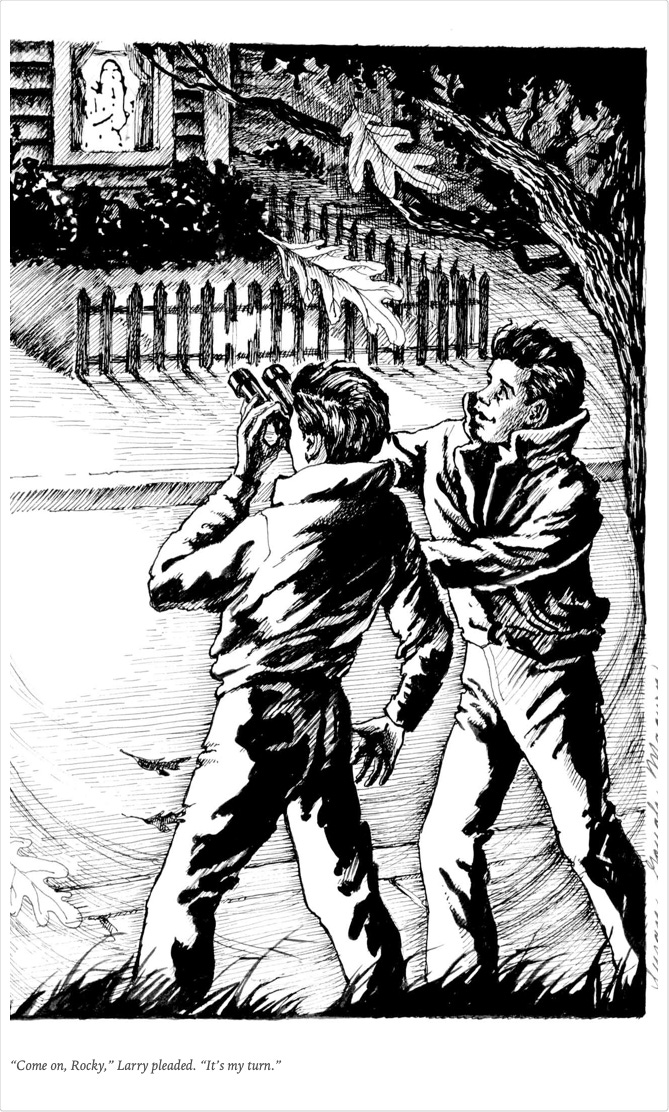

The frontispiece to that first book showed two boys, Larry Peters and his friend Rocky King, square-jawed American boys, standing side by side in a fierce wind, the collars of their windbreakers or flight jackets up, their hair blowing in a style that became popular in men’s clothing advertisements much later in my life. Rocky was holding a large pair of binoculars to his eyes and peering into the darkness. In that darkness, one could see a lighted window, and in that lighted window, one could make out, if one studied the illustration closely and carefully enough, a shapely woman, presumably the brunette of the title. Larry was reaching for the binoculars, and under the illustration was a line from the book: “Come on, Rocky,” Larry pleaded. “It’s my turn.”

I READ The Shapely Brunette twice that day, and a third time the next day. Then I read every other Larry Peters book that had been published. From then on, I waited impatiently for new books to come out. I was hooked on Larry Peters, and I wanted my friends to share my enthusiasm. I wanted them to read the books, to read them as thoroughly as I had read them, to absorb them as I had, so that we could use them in our friendship, use them as a constant, a given, in our conversation together, add them to the context of our conversations for the same reasons that one adds manure to garden soil: so that the plants will flourish, grow thick and intertwined, flower profusely and brilliantly. But most of my friends didn’t share my enthusiasm for Larry Peters, his adventures, Kittiwake Island, or the habit of mingling reading with dreaming. They didn’t notice everything that I noticed. Most didn’t even recognize, in the frontispiece to The Shapely Brunette, the image of the shapely brunette in the lighted window.

“Wishful thinking,” said Raskolnikov. “That’s just a way of drawing. The artist uses a few quick strokes of the pen to suggest that the shade is down without inking in the whole shade. We had that in art class already. It’s just an artist’s trick. It’s not really meant to represent anything. You only see a woman there because you want to.” He jabbed me in the ribs.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.

Share this post