15

AS TIME PASSED, the snapshot stayed in my mind. I could recover the picture of myself sitting on the dock whenever I wished, just by closing my eyes and willing it to appear. I assumed that it was a memory, but unlike most memories, the picture became clearer with time, more detailed, more precise. I could feel my sensations better, more clearly, as time passed. At the same time, however, much about this memory made little sense to me, and explanations eluded me. Where was I? How did I get there?

I had my suspicions. My maternal grandmother, Gumma, was a believer in recurring dreams that passed from generation to generation, dreams that arose from acts of such power that they inspired emotions too strong to die in a single lifetime. She claimed to have one herself, a dream about rushing along a curving corridor, opening a series of doors, and falling after she opened the last one. She was convinced that this derived from something terrible her grandmother had done. My mother had one, one that I had learned about when I told her, years before, about a dream that I had had while I tossed restlessly during a bout with one of the childhood diseases, something that made me feverish.

It was a dream in which nothing happened. There was a featureless landscape; it might have been a desert or tundra. In the foreground was a post, and from the post a line of some kind dangled. The post, and, even more than the post, the line dangling from it, made me feel miserable, nauseated, frightened, horribly empty, as if something terrible had happened and things would never be right again. When I told my mother about this, I did so reluctantly, because during this restless and feverish time I had, by assembling in a careful, step-by-step, logical fashion the few facts I knew, the rumors, assertions, wild claims, and flights of fancy I had heard, and the mystifying hints in a pamphlet my mother had left in my room, arrived at a clear theoretical understanding—which in form resembled the instruction sheets that came with the model airplanes I had become fond of building, an insert-part-A-into-part-B understanding—of what men and women did when they “went to bed together,” and had discovered, by way of looking for an experimental method to test my theory, masturbation. I had a hunch that my unsettling dream might have something to do with that.

“Oh, Peter,” said my mother. “I have that dream, too.”

“You do?” I asked.

“Oh, yes. But I know why.”

“I think I know why, too,” I said, looking at my hands.

“It’s because of the rowboat.”

“The rowboat?”

She explained a painful memory. One Sunday when she was a little girl, Gumma and Guppa had organized a picnic on one of the islands in the bay. Friends had traveled to the island in boats, and after a while the children had wandered away from the adults to amuse themselves. The amusement for the youngest children consisted of throwing sand and pebbles into a dinghy that Garth and May Castle had used to row from their sloop to the island. The rowboat was tied to a piece of driftwood that the Castles had thrust into the sand. In time, the children succeeded in sinking the dinghy, and they cheered when it settled to the bottom. When it was discovered, none of the adults had been particularly angry, in fact most had thought the incident funny, but my mother had felt ashamed of her part in the business, and she insisted that a sudden wind had arisen and blown the sand and pebbles into the dinghy while the children watched, helpless and aghast. As time passed, she became more ashamed of the lie than of the act it was meant to hide. She thought that the recurring dream showed the piece of driftwood and the line leading into the water. I thought for a while that my sitting-on-the-dock memory might have been a more precise version of my post-and-line dream, but I have never been a believer in such things, so I continued to look for another explanation.

I thought that the dock might be on Small’s Island, but things were not quite right. For one thing, I was not quite myself in this scene. For another, the island was not quite Small’s Island. I was reminded of the eerie feeling Raskol had described so many years before, when he told the Glynns and me about his crawling through a culvert into what he took to be another world. Finally, with all the force of the truth, the explanation hit me. I was, in this snapshot, the young Larry Peters, but not quite the young Larry Peters with whom I was familiar. I was the young Larry Peters as he would have been if I had been the young Larry Peters. Sitting on the dock, I was Larry Peters before the adventures began, before the family had prospered, when Larry’s father was still struggling to make his gewgaw business go, Larry Peters at a time of his life about which Roger Drake had told me nothing, at a time when I was free to construct any Larry I wished. Something else struck me at nearly the same time. The picture of myself as the young Larry Peters that I had in my mind was becoming clearer with time, rather than fading, because it was not a memory: I was making it up.

In Topical Guide 201, Mark Dorset considers Dreams; Sex Education Circa 1953 or 1954; and Guilt from this episode.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

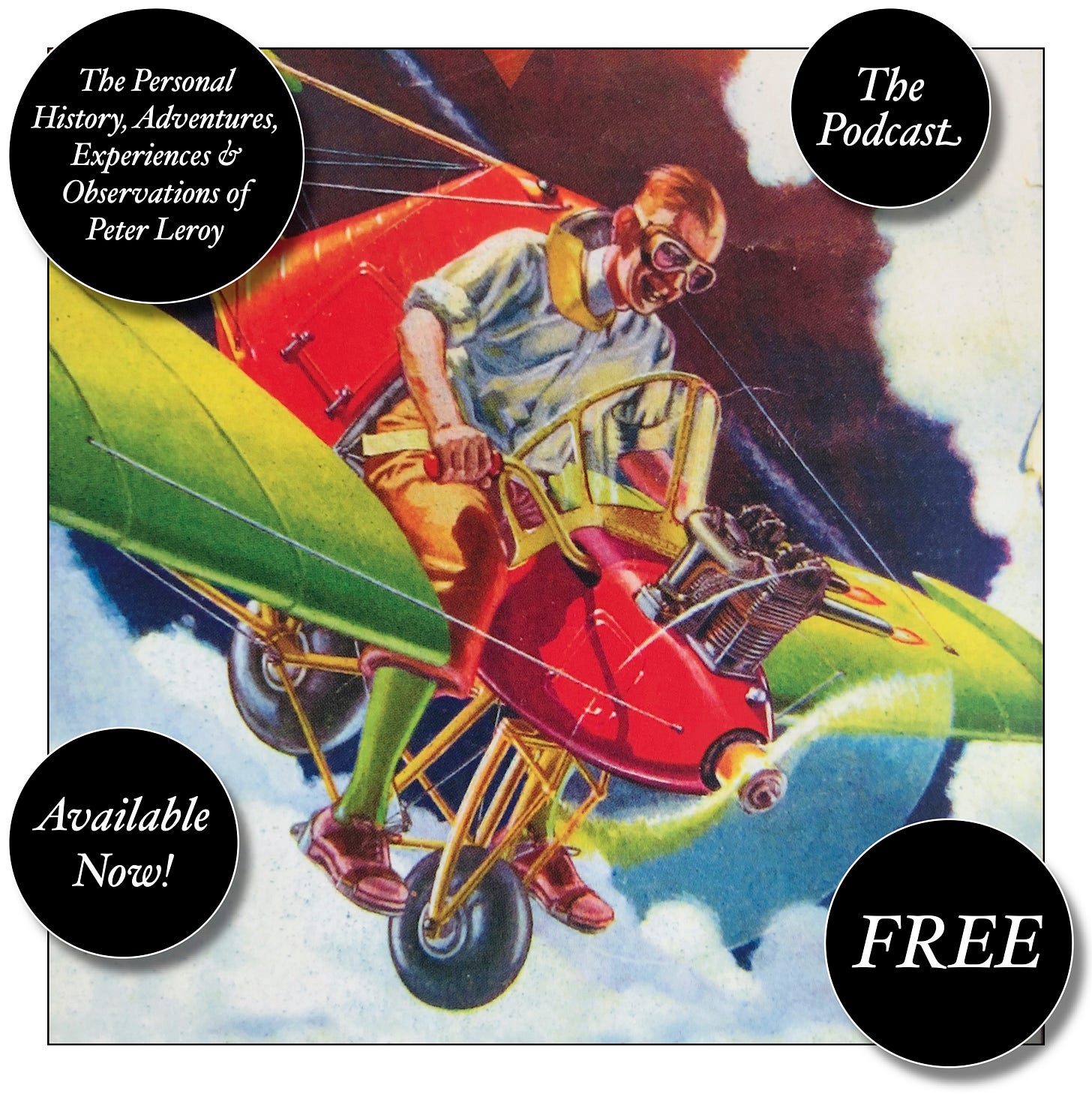

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.