Lorna, holding Herb’s hand to steady herself, stepped into the rowboat. The first notes drifted out over the lake, just as Herb pushed off from the dock, and — what luck! — “Lake Serenity Serenade” turned out to be lilting and beautiful, and the sax section of the Triple-A Orchestra outdid itself. It was a great stroke of luck, one of those happy accidents we discredit when we hear an account of their happening to someone else, although they figure so prominently in our dreams and daydreams and are sometimes our only reason for hope.

In Time and Free Will, his essay on the immediate data of consciousness, Henri Bergson remarked that joy and passion are “very like a turning of our states of consciousness toward the future. As if their weight were diminished by this attraction, our ideas and sensations succeed one another with greater rapidity; our movements no longer cost us the same effort.” That is precisely what Herb, in his joy and passion, experienced, though he didn’t give it a thought. He just found the rowing remarkably easy. The water seemed as insubstantial as the moonlight that played upon it. Herb took long, languid strokes. When he lifted the oars, silver droplets fell from the blades, leaving silver circles on the surface, circles that widened in the wake of the little boat. The boat glided on, as easily as if it were floating above the lake, through the clear air of the Whatsit Valley. Lorna reclined in the stern and looked at the stars. She let her fingers brush the surface of the water on either side of the boat. They left rippling wakes of their own. Herb couldn’t see where he was going. He had his back to the bow; he saw only Lorna. He was quite content. He saw her smiling, and he was delighted to see her smiling. This was a smile of contentment, of serene joy.

“Lorna,” he whispered, “close your eyes.”

Still smiling, she closed her eyes. Herb went on rowing.

“Imagine that you see your future,” said Herb. “Tell me what you see.”

Lorna drew a breath, and the air she inhaled thrilled her. For a moment, she could hardly believe that she was breathing ordinary air, the effect was so intoxicating. She had imagined her future so well that she seemed to have taken a breath from that time, and her smile widened because she’d tasted her future and found that she liked it. Herb was rowing toward the future; the past was in their wake.

“It must be good,” said Herb, watching her.

“It is,” said Lorna. “Close your eyes, and I’ll tell you what I see.”

“If I close my eyes, I won’t be able to see where I’m going.”

Airy laughter, almost giggles; silvery, moonlit laughter.

“Of course I can’t see where I’m going,” said Herb. He swallowed and dared to say, very softly, “But I can see my future.” Then he closed his eyes. “I closed my eyes,” he said.

“I see you,” said Lorna.

Herb drew a long breath and found it so intoxicating that he gripped the oars tighter to steady himself. “Does that mean what I hope it means?” he asked.

“I hope so,” she said.

“Do you want to know about my plans?” Herb asked.

“Of course I do,” said Lorna. “But it won’t make any difference what they are; it’s you I love, Herb, not your plans. Do you want to know mine?”

“Wouldn’t make any difference to me either,” said Herb.

Lorna sat up suddenly. “Are we engaged?” she asked.

“I hope so,” said Herb.

The crowd inside the ballroom called for an encore of “Lake Serenity Serenade” and got it, and during the encore Herb and Lorna made love. It was, compared to what either had tasted so far, a feast. All the senses were invited, and there was no reason this time to leave the mind, the heart, or the imagination out of the fun; there was something for all of them — some rocking rowboat, rocking, rocking, beneath their tentative caresses, balsam scenting the air, moaning saxophones, Lorna leaning over Herb, running her hands over his chest, imagining modeling him in clay, tugging, pushing, kneading at his skin as if it were clay, pushing him backward and pulling his pants down, laughing, the rowboat rocking, rocking, rocking, whooops, rocking, grabbing for the gunwales, ouch, ooh, a splinter, thin sliver in the palm of Lorna’s hand, Herb’s slow, cautious extraction, drawing the sliver out so slowly that the sweet pain made Lorna run her hand between her legs, salty taste of Lorna’s blood, fluttering tickle of Herb’s tongue in Lorna’s palm, Lorna stretching out, her slow undressing, moonlight turning her to ivory, Herb imagining her in ivory, articulated here, here, here, here, wavelets lapping the sides of the boat, distant voices, laughter, a call, a shriek, stars twinkling in the night sky and bouncing in the water, Lorna’s foot dangling in the water, Lorna twisting around and settling onto Herb, wiggling to feel Herb in her, the long curved edges of the gunwales pressed into Herb’s calves, his feet dangling in the water, the wavelets tickling the soles of his feet, and at the moment of his coming the tickling becoming too much to bear, his laughing, laughing, laughing, their collapsing into the boat like fish landed after a struggle, flopping over the seats, bruising themselves on the edges and corners and oarlocks, and laughing, laughing, and subsiding, and lying with their arms around each other, just looking out over the water, the flickering water, silver with moonlight, but now, oddly, gold here and there, and even red, and —

Lorna lifted herself on one elbow and looked back toward the ballroom. It was in flames. They hurried into their clothes and began rowing back, sitting side by side, pulling at the oars, keeping their course by keeping their fire-formed shadows in the boat, and Lorna, who was so giddy with the promise of the future they had tasted that she couldn’t resist her happiness, even though she worried about the fire, turned toward Herb and asked, “You don’t think we did it, do you?”

In Topical Guide 293, Mark Dorset considers Moonlight; Fire: As a Metaphor for Passion; and Passion: Fire as a Metaphor for from this episode.

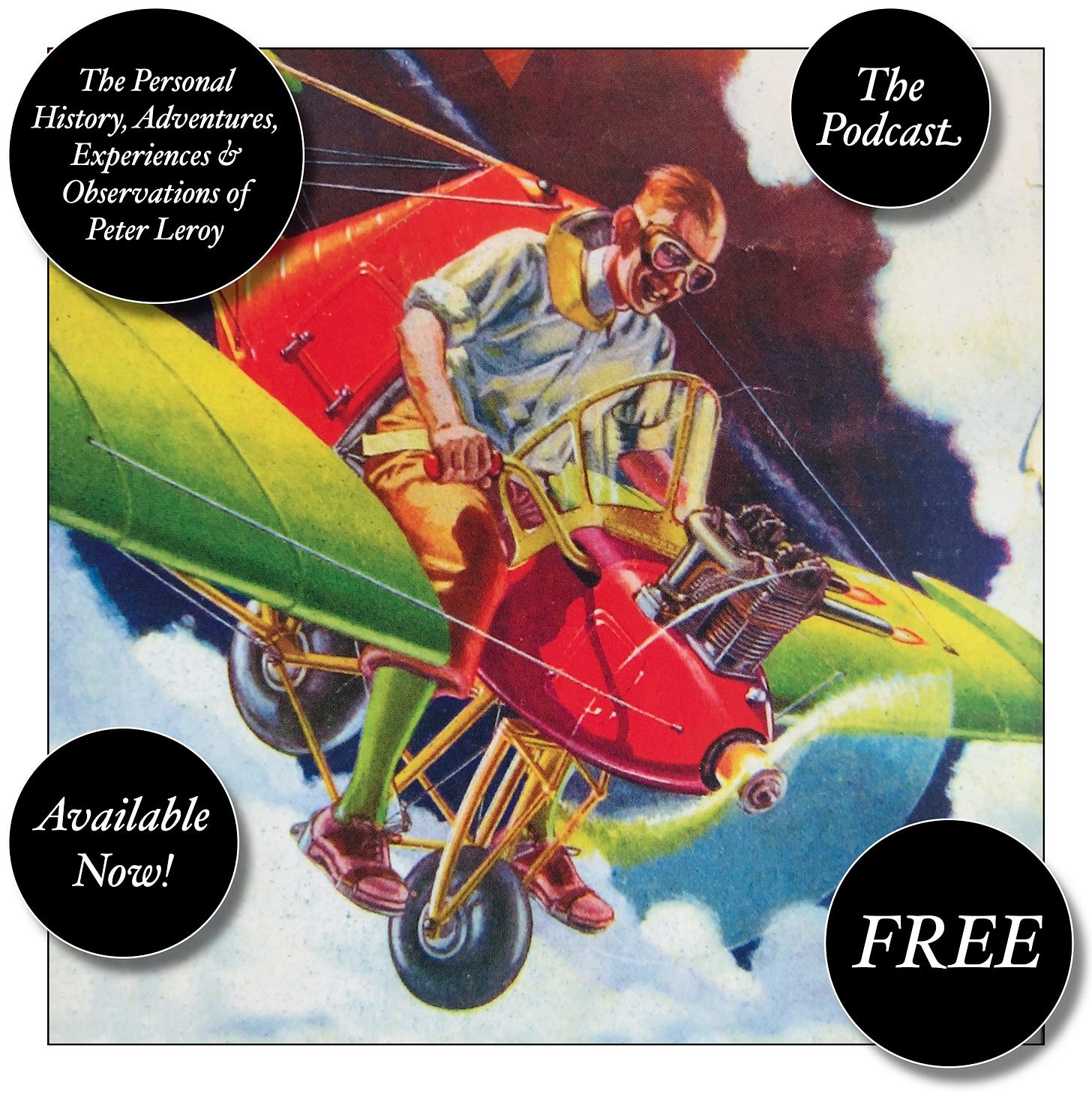

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post