In the back of Mark’s mind, he knew — or at least he had some kind of hunch — that Herb and Lorna were the people he wanted to — needed to — talk to, and so he visited them often. As Studebaker’s fortunes fell, Herb spent less and less time at the showroom and more and more time at home, tinkering, so the chances were good that he would be at home whenever Mark dropped by. To alleviate his worries, Herb had thrown himself into building equipment for the tour of the United States that he and Lorna had always wanted to make. Mark would often find him working on the trailer he was building from pieces of old Studebakers. He might be cutting up a garden hose to make a speaking tube to run between the trailer and the car that would pull it. He might be building, from parts of a sewing machine and a vacuum cleaner, one compact device that would do the work of both and make toast to boot.

Lorna also spent more and more time at home, in part because the demand for slide rules was falling, but also because she wanted to keep an eye on Herb, to be sure that his enthusiasm wasn’t a mask, that he wasn’t falling into despair over the Studebaker decline. Most often when Mark dropped by he would find her cooking, or planning the route for their tour, or working at recreational mathematics and logic problems, sitting on the porch or on the sofa, that scratchy rose-colored sofa, with a Whitman’s Sampler beside her.

One night at the very start of summer vacation, after Mark had finished his junior year in college, he was walking to the Glynns’ along the dark and twisting road that had once been the driveway to the mansion, burned long ago, for which the Glynns’ house had been the carriage house. A convertible passed him. In it, Margot was sitting beside a dark-haired young man who wore a blue blazer, a young man who seemed self-confident and rich. In a few minutes, a motorcycle passed. Martha was perched on the back of the seat, holding on to a sandy-haired guy with thick arms, a guy who looked self-confident and lusty. Mark had never actually seen Margot and Martha with other boys before. He realized that he had hoped their dates were straw men, intended only to show that they had tried to fall out of love with him but failed. He walked on to their house, and he stood outside for a few minutes, debating with himself whether he ought to go in and find out from their parents who these rivals were. He decided not to go in. He began walking. He was afraid that he might on this night lose not one but both, and that fear made him weak, empty, desperate. He walked into town and bought some beer, and then he walked back to the Glynns’ and sat outside, drinking the beer and waiting. Mr. and Mrs. Glynn went to bed. The dark and the silence made Mark terribly miserable, and the beer made him a little dizzy. He began walking again.

He found himself, beery and blue, at Herb and Lorna’s. It seemed as if one minute he was on their porch, and the next minute he was sitting on their sofa, saying, “It was right here on this sofa that I fell in love, and it was the most miserable thing that ever happened to me. The most wonderful thing and the most miserable thing. The most miserable thing. Let me explain why I say that. I say ‘the most miserable thing’ because it isn’t going to work out. It just isn’t going to work out, and it isn’t going to work out because there isn’t any way it can work out. I can’t have two wives, it’s as simple as that.”

Somehow, he next found himself sitting between Herb and Lorna at the kitchen table. Herb was pushing a hamburger at him from one side, and Lorna was pushing a huge plate of something that he didn’t recognize at him from the other.

“What is that?” he asked Lorna, trying to be very precise in his speech because he had begun to sense that he was a little drunk, and he didn’t want it to show.

“This is potato salad,” she said. “And Herb’s got a hamburger for you.” She dropped her voice. “You ought to eat something, Mark,” she said.

Mark looked closely at the potato salad. “It looks as if it isn’t finished,” he said. “In other words, that is, it seems to me that someone stopped making it in the middle. It looks like just potatoes.” He chuckled.

“Oh,” Lorna said, surprised, laughing. “It’s German potato salad. It doesn’t have any mayonnaise.”

“And you’ll never eat any that’s better than Lorna’s,” said Herb.

“You know,” Mark said, “I know why you’re doing this. You’re worried that I’m drunk and I won’t be able to walk home if I don’t eat something.” He put his arms around them, and as soon as he had he felt that he had put the three of them into an awkward position. “You don’t have to worry about me,” he said. He gave them a squeeze that he would never have presumed to give them if he had been sober, and then he let go of them. “I’ll be careful,” he said.

“You have to at least try some of Lorna’s potato salad,” said Herb.

Mark laughed. He adored them. There was in Herb’s voice such boundless pride in Lorna’s potato salad that Mark gave in and began eating at once. He stayed for a couple of hours, eating a bite now and then, taking a swallow of coffee now and then, and talking, talking, talking. He told them all about Margot and Martha, how he felt about the girls, how the girls felt about him, how the three of them felt about each other, how hopeless their prospects seemed to be. They were wonderful listeners. They didn’t offer a word of advice, but Mark left them feeling that things might work out. He still had no idea how exactly they might work out, but he had the general idea that everything might, somehow, be all right.

Only when Mark was about halfway home, when rain had begun to fall and his memory had begun to clear, did he realize that not only had he confessed to them, in a rambling, uncertain way, grinning, blushing, groping for a suitable vocabulary, that he wanted to go to bed with Margot and Martha, to make love to both of them, but he had also admitted that he had no specific idea how, gracefully, admirably, romantically, such a thing might be done. He remembered the looks they wore: looks of interest and curiosity but not a trace of embarrassment, and he even remembered telling them about the way his mother had blushed at the end of the evening when he had brought Margot and Martha home to dinner for the first time. A little tipsy, she had giggled and said to him before he went to bed, “Remember that you can’t be in two places at once.”

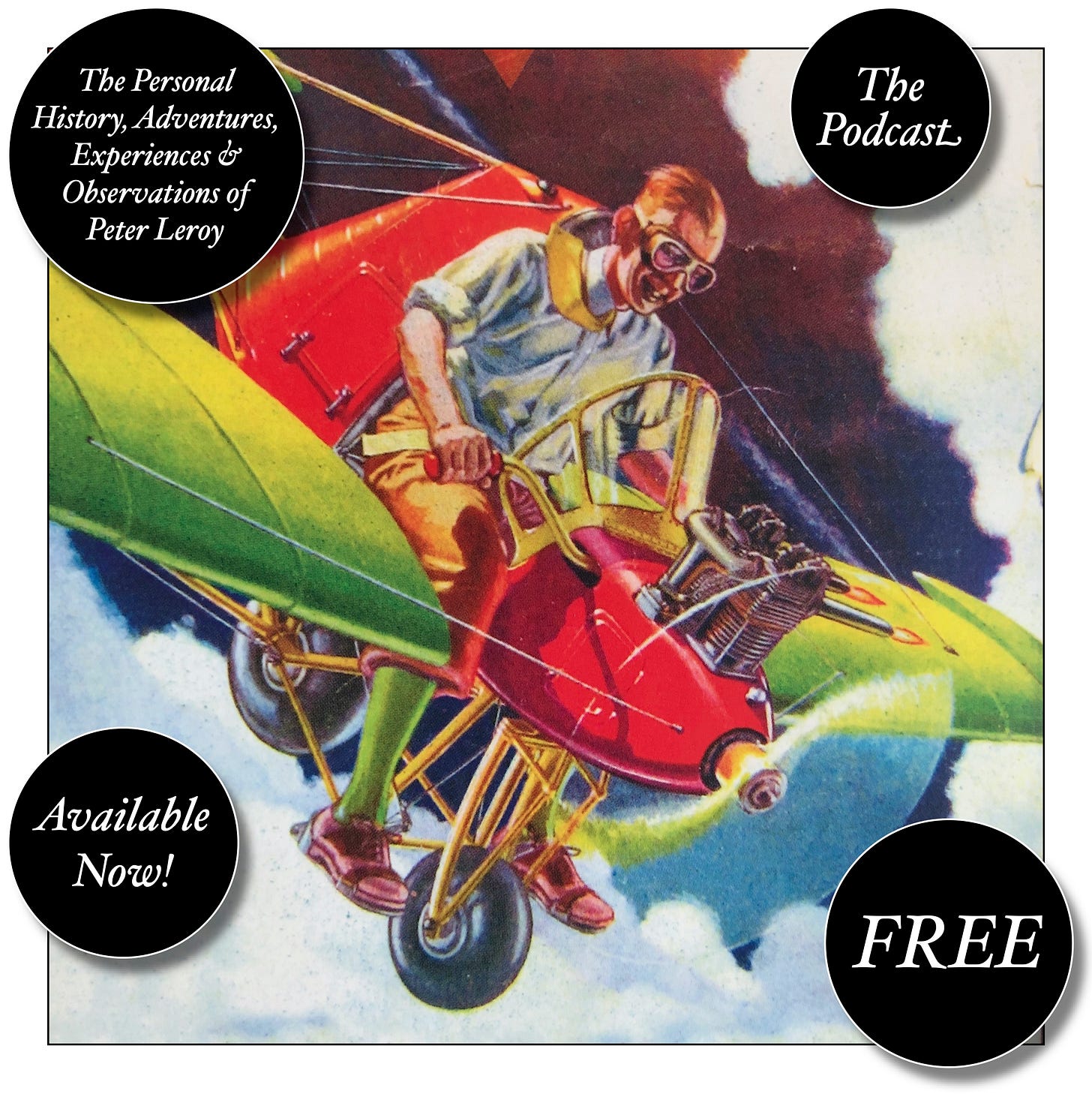

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archiveor consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.