“Well, when I got called, I figured that if I sold some goods to the other boys while I was in France, I could keep sending money to my mother. I had to get some goods to sell, so Uncle Ben and I came to Chacallit, that time when you and I met.”

“But, do you mean that when you came to our house selling books, you were going to try to sell some goods to my father?”

“No. Oh, no. Heck no, not right in the manufacturer’s back yard. I just came to sell books — to earn some money for the trip back to Boston. Then, in the war, I sold a lot, and then, when it was all over and we were just waiting around to be shipped home, that’s when Pershing gave me my medal.”

“Medal?”

“You know the story about Pershing shaking my hand because I fixed those cup handles — well, it’s not true. He never shook my hand. He gave me something, a coarse medal, you could say.”

Herb hopped out of bed. For a moment he was a shadowy figure, barely visible, receding; then suddenly he was silhouetted in the bedroom doorway when he snapped the hall light on; then he was an illuminated figure, receding. Lorna noticed (she had a practiced eye) his thin legs, the prominent tendons behind his knees, his knotted calf muscles, his droopy buttocks, a bruise on his shoulder blade, and was astonished at how much she loved him. In a while he was back, and for just a moment in the light of the hall before he turned the light out she saw the grin on his face, the unruly strands of white hair falling over his forehead, his little old penis, and she was so pleased with him that she got the giggles for the first time in she didn’t know how long. He had brought with him the same metal box from under his workbench, from which he had earlier produced his drawings. From it he now pulled a little leather pouch. He spread the top open and held it out toward her. Lorna cupped her hands under it. Into them dropped the button Pershing had given him.

“Herb!” she said at once. “This is from Chacallit! I know it is! They made lots of these little buttons. Luther had the most ridiculous argument about how they would raise morale. But I didn’t work on them. Luther and I quarreled, and — oh, but I made some little statues. I used to slip them into the Comfort Kits that I put together for the Red Cross. But — oh, that’s beside the point. Do you think General Pershing bought this button? No, of course not. Someone must have given it to him. Maybe those buttons did raise morale. I suppose the men traded them, or sold them, used them to barter for whatever they needed, for soap or — Soap! I have to tell you about Baltimore. Oh, I’m sorry, I interrupted you. Go ahead.”

“Lorna. Lorna. Do you know what they called those?”

“Called those?”

“Those carvings that came in the Comfort Kits. You were my competition, do you realize that? Do you know what they called those carvings?”

“My carvings?”

“Yes. You were famous. They were famous anyway.”

“Famous?”

“They called them Comfort Cuties.”

“Comfort Cuties. I like it. It’s cute.”

“Cute. Well. Oh, God, cute reminds me of something ugly. And I mean ugly. You know, it was really my Uncle Ben who invented moving goods?”

“Animated. We called them animated pieces. With moving parts. Oh, Herb — moving parts. May loved that, moving parts.”

“You told May?”

“I had to tell somebody. But moving parts. Do you remember those charms? Those charms in Life? I wanted to make charms — I still want to make charms — with moving parts. You know, parts. Can we, Herb? Can you design them, and I’ll carve them, and you sell them?”

“Sure. Of course. Why not?” He paused. “Lorna — ”

“Mm?”

“I always thought you’d be ashamed.”

“I was ashamed. I told you. I was terribly ashamed. But I loved it too. I was just a girl. I didn’t understand that there was nothing to be ashamed about.”

“I didn’t mean that. I mean ashamed of me.”

“Ashamed of you? My God, I’ve admired your work for years. I think you’re — a genius.”

“A mechanical genius.”

“A mechanical genius. That’s right.”

“And you. Those little people. They were beautiful. You’re — an artist.”

How the bedsprings sang that night!

“Careful, Herb,” said Lorna, “we’ll set the whole neighborhood on fire.”

Perhaps they were no longer up to the vigorous, eager, reckless pleasures of youth, but those are rather conventional pleasures anyway, and Herb and Lorna were uniquely capable of something else, something richer, something skilled and clever, the considered, measured pleasures of a couple of master couplers, ready at last to reap the harvest of decades of imagination, plant the seeds for the mature masterpieces of a pair of love artists.

In Topical Guide 388, Mark Dorset considers Allusions, Literary: Ars Amatoria from this episode.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archiveor consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

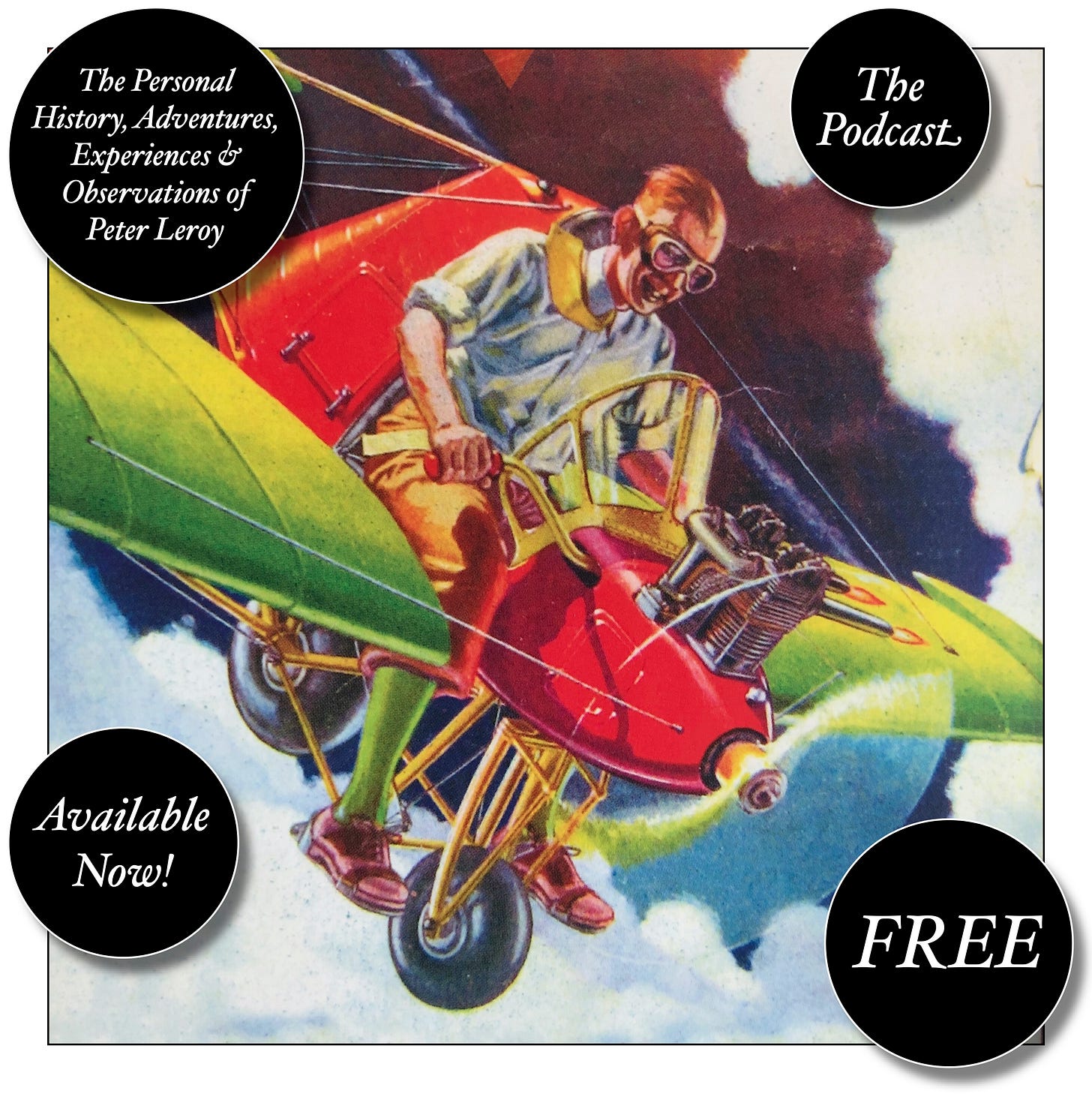

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.