Matthew has a twinkle in his eye. He sips his tequila. “I think he’s not just a nut,” he says. “I think he is a very singular nut.” He pauses and turns the twinkle toward Belinda, enjoying the idea that he and Belinda know something that Liz doesn’t. As soon as he says what he’s about to say, Liz will understand that he has a life without her now, has had experiences that she hasn’t, knows things that he didn’t know when they were together. She will see that there are mysteries about him now, and there’s the possibility that she might want to probe them. That possibility thrills him. “I think he might be the Neat Graffitist,” Matthew whispers. “The guy who writes those odd messages we see all over the place.” Though he delivers this explanation in Belinda’s direction, it isn’t for her; she doesn’t need it. It’s for Liz.

“What messages?” asks Liz. “Ooh, tell me.” Matthew doesn’t hear the note of jealousy he’d hoped to hear, just curiosity. He’s disappointed.

“Well, first of all, I have to tell you he’s not the one,” says Belinda. “I saw him. I meant to call you, Matthew. I’m sorry. I can’t believe I forgot. I know what a fan of his you are.”

“That’s all right, but tell me about it,” says Matthew.

“And tell me about it,” says Liz.

“Okay,” says Belinda. She leans inward, conspiratorially, and Matthew and Liz do likewise. “Basically,” Belinda says, “he’s a guy who writes graffiti.”

“Very neat graffiti,” says Matthew. “You see them in particular places. Smooth, flat places. Like the side of a mailbox. Or those silver boxes you see on corners — I think they’re some kind of telephone switching box.”

“Or on newspaper boxes.”

“Uh-huh,” says Liz with great seriousness, as if they’re telling her about a network of spies that they’ve stumbled upon.

“Very neatly lettered,” says Belinda.

“In Magic Marker,” says Matthew. “No spray cans or anything like that. He writes little philosophical statements.”

“But not all the time. Some of them are more like headlines,” says Belinda. Matthew raises his eyebrows and jerks his head in the direction of the man in the yellow shorts. All glance at him. He’s clipping another headline from the newspaper.

“Right, but this isn’t the one,” says Belinda. “I saw him on State Street, near the Devonshire. He’s shorter, and he has a round face, and he’s a happy guy, crazy but happy, nothing like this one.”

“You’re sure the guy you saw was the one?” asks Matthew.

“Yes. I’m sure. He had about three garbage bags full of possessions, and he had a cardboard sign propped up against each one. The signs were more of his statements. The same printing. It was the guy. No doubt about it. And he was talking, just going on and on. Not loud, just talking, but to people, to the crowd. And as I went by, he said, ‘I did what they told me to. I took the medicine and fell asleep.’”

“Well,” says Matthew. He shrugs to show that he’s not convinced, but to Belinda his shrug says more than he intends. It says that he isn’t willing to believe that the man she saw is the Neat Graffitist. She realizes that Matthew’s jealous. He wants to keep the Graffitist for himself. She’s surprised to find that this makes her feel weary, not annoyed.

“So, anyway,” says Belinda, explaining for Liz, “he’ll write something like ‘Arab terrorists supply drugs to typists in the State House.’ Or one of them, his biggest work so far — it covers most of a sheet of plywood — is about some group that he accuses of killing — pigeons, is it?”

“Ducks,” says Matthew.

“Killing ducks in New Jersey,” says Belinda. She wonders, without caring very much about the answer, how much longer she’ll bother seeing Matthew.

“Right,” says Matthew. “But the main thing is that he always makes some kind of comment. He doesn’t just make a statement. He always draws a conclusion about it. He almost has a sort of philosophy. Like the one about the terrorists supplying drugs to — actually it’s ‘word processors in the State House,’ not ‘typists.’”

“You’re right,” says Belinda. How much longer will she care to go on drifting with him through these nights of dinner, drinks, and drunken conversation?

“The full text is: ‘What makes Arab terrorists supply drugs to word processors in the State House? Nobody deliberately chooses to do an evil thing.’”

“Matthew collects these writings,” Belinda explains to Liz. She drains her glass. Her time with Matthew seems to have added up to nothing. How much more time will she be willing to spend on him?

Matthew shrugs, grins. “A little weird, I guess,” he says. How much weirder Liz and Belinda would think it was if they knew that he has copied his entire collection onto the wall of his apartment, above the open section, imitating the neat printing of the originals, or that he has added some of his own, counterfeits, indistinguishable from the others?

[to be continued]

In Topical Guide 489, Mark Dorset considers Evil from this episode.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

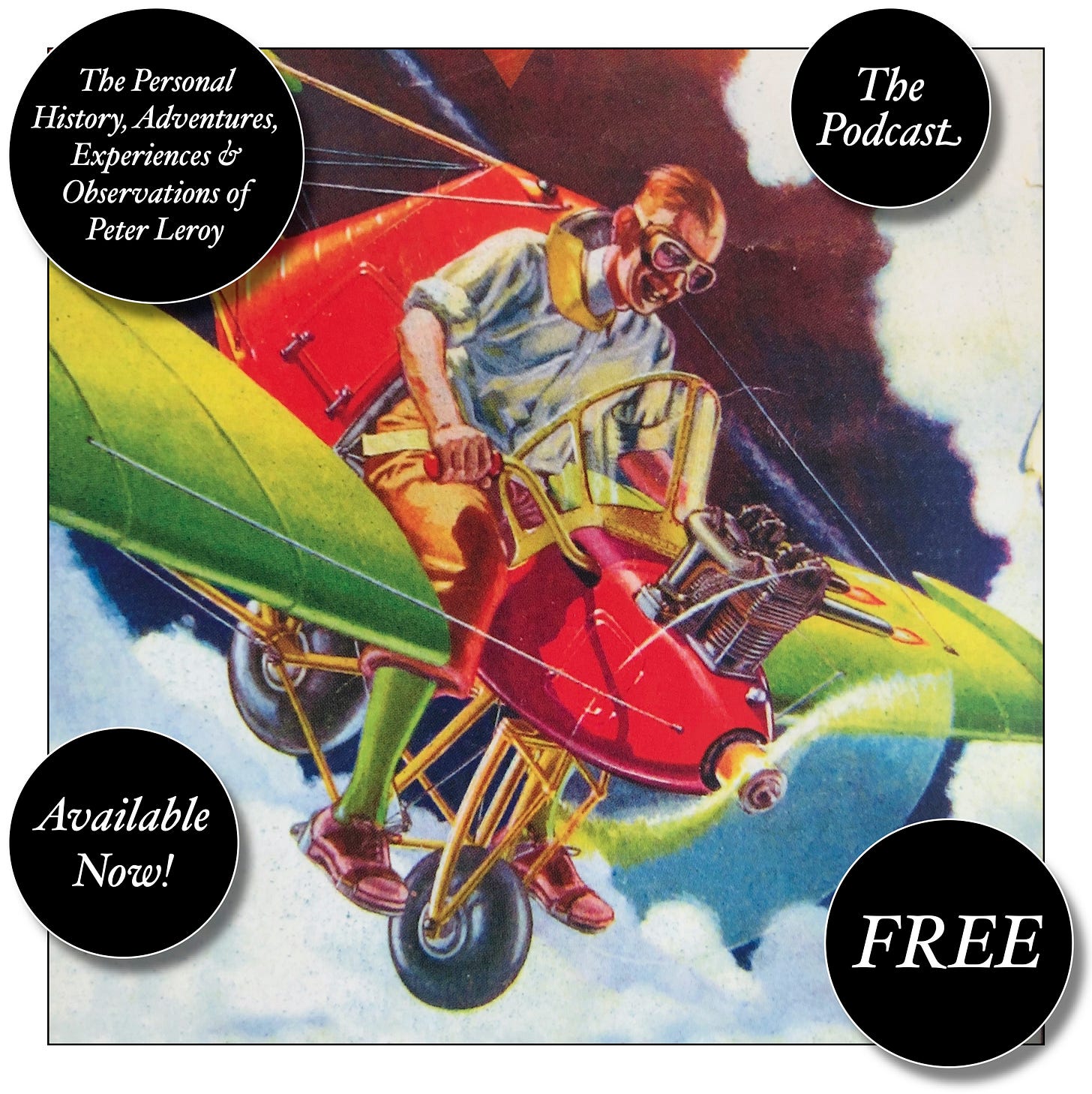

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies and Herb ’n’ Lorna.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.