“Could I please have some water,” calls the man in the nylon shorts without looking up from his work on the papers.

Liz and Belinda respond by giggling like children at a family gathering, convulsed by the bizarre behavior of their intoxicated elders. Matthew sits upright and says, “Shhhh.” A gust of fear has disturbed his fun. He wants to go on, but he doesn’t want the man in the nylon shorts to realize that they’re talking about him. He is certainly a crazy man, and he’s sure to be enraged if he finds that they’re talking about him. Matthew doesn’t want the women to know that there is fear behind his wanting them to be quiet, so he pours more tequila into the glasses and tries to assume the sardonic tone of B. W. Beath. He leans inward and whispers, “Maybe there’s more than one. Or maybe he has assistants. This guy might be part of a vast conspiracy.” He makes the gesture of lettering on an imaginary wall between them, in small, neat block letters, and says as he writes, “‘Ectomorphic joggers observe diners in Indian restaurants, take notes. Watch what you say.’”

Belinda begins to giggle. She tries to stifle it, but it breaks out, and it infects Liz and Matthew, and they begin giggling and stifling their giggles, and tears run down their cheeks. Matthew hasn’t laughed like this for a long time. He glances around the room. The noise level is so high that no one has particularly noticed their laughter. The hockey players are shouting stories at one another. The academics are not quite shouting, but they are making emphatic points in loud voices.

“Another one,” says Belinda, “is, ‘Mail handlers at South Street Annex have nurses in their union.’”

“So what?” asks Liz.

“Just what I wondered when I saw it,” says Matthew. “And the next day someone had written under it, very neatly, almost in the same style as the original, but in a different color, ‘So what?’” Only after he has said this, and Liz is laughing at it, does he realize that he took Belinda’s line from her. “Sorry,” he says.

She grins a mirthless grin and makes an it’s-nothing gesture with her hand. “Anyway,” she says, “a couple of days later he added — how did it go?”

“‘Happy people don’t cause trouble,’” says Matthew.

“Yeah,” says Belinda. “He must have seen the note and realized that he forgot to add his comment. So he made a comment on the comment.”

Liz makes no response.

“I guess you had to be there,” says Belinda. “But,” she says to Matthew, “I have a hot piece of information for you.” There is drama in her voice — some sarcasm, too. “He calls himself the Culture Guerrilla,” she whispers.

“The Culture Guerrilla?” asks Matthew. “How do you know?”

“Well, when I saw him, I — ” She is about to say, “I was with three guys from MIT,” but she decides against it and says instead, “I stood in a doorway for a little bit and — observed him. And there were three young guys there who were watching him, too. Two of them were real experts. They knew more about this guy than you do, Matthew.” Now why did I say that? she asks herself. That wasn’t fair. “Well, probably not. You are his biggest fan, but they could quote dozens of his sayings, and not only could they quote them, but they knew where each one was. They had a chart. They were from MIT.” There! She said it, and what a delightful thrill it gave her to say it. It’s a wonder that she can keep herself from saying that she has become the darling of a small set of graduate students at MIT, a wonder that she doesn’t tell about the hours she spends talking, talking, talking with them, about the way they took at once to Picture Frame, sitting at the computer for hours, without caring whether there was a dead body in it or not, about the way they seem to her to swagger, their confidence and the way it electrifies her, or the amazing sexual energy of Massimo, the leader of the pack, whom she calls, as all his American pals do, Max. “Anyway, according to these kids, one of his messages says, ‘Culture guerrillas eat at Ike’s,’ and they figured that he was giving himself away. Deliberately. That this was like a signature. Like a painter signing a painting.”

“No, I don’t think so,” says Matthew. “In fact, that doesn’t even sound like one of his. Did they say there was a second part? Is there a comment?”

“Yeah. There is. ‘They stuff themselves, but their souls are hungry.’”

“No, that’s not him. It’s too pat. It doesn’t have that twisted quality. These MIT guys probably wrote it themselves. You know, I wouldn’t be surprised if they did! I wouldn’t be surprised at all. I’ll bet he’s spawned imitators, and now he’s even inspired parodies.”

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

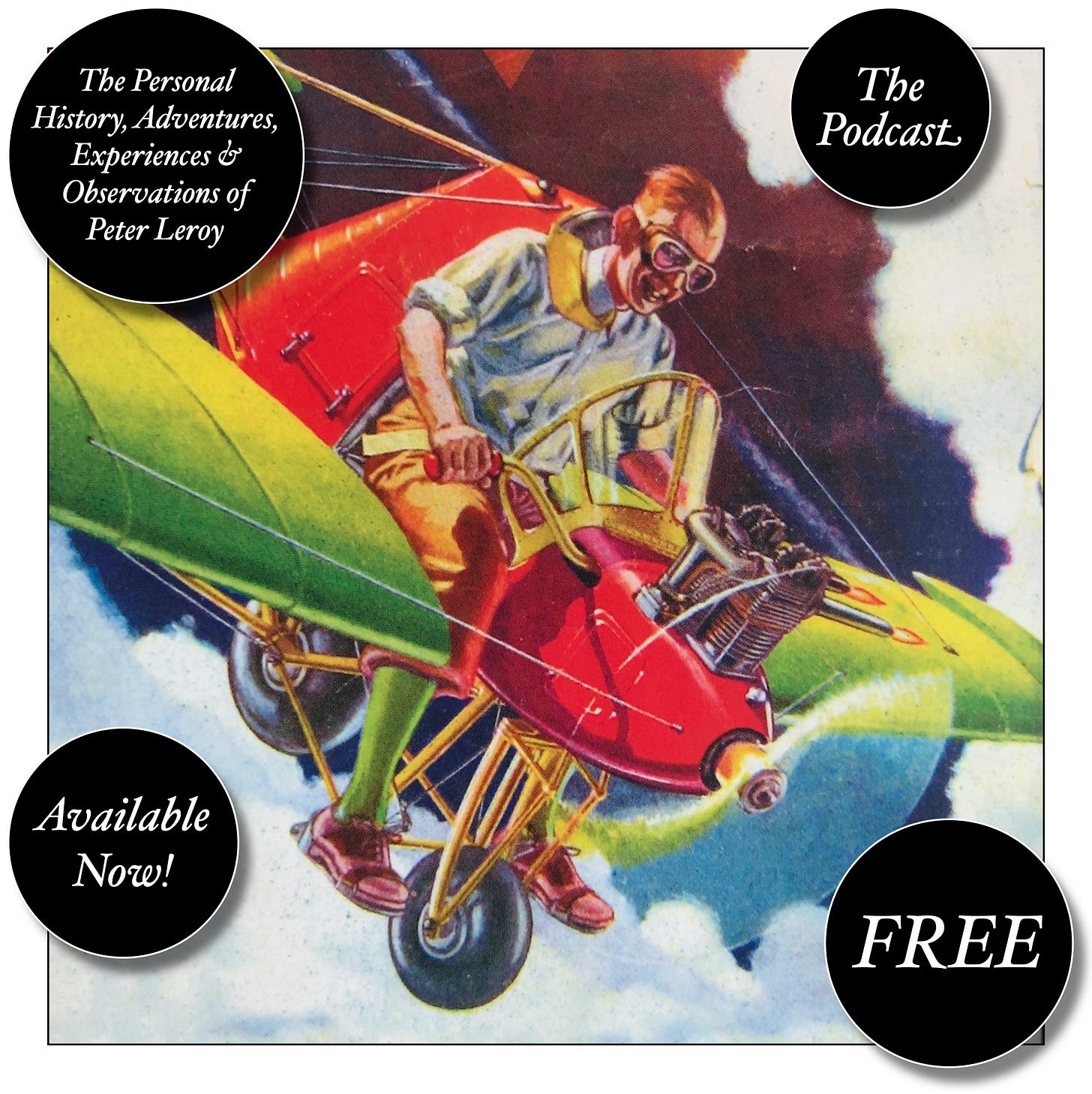

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies and Herb ’n’ Lorna.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.