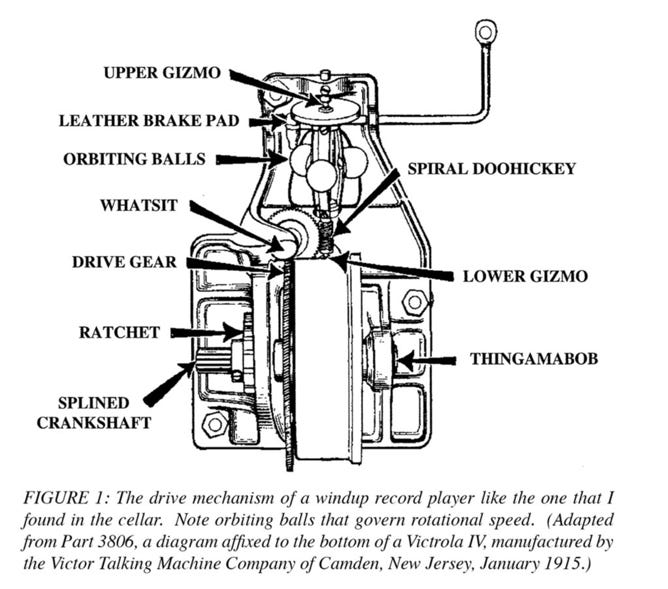

THE THING AS I FOUND IT was, essentially, this: a motor driven by a spring that the operator wound with a large crank (see Figure 1).

The motor was mounted vertically inside an oak box, with the shaft emerging from the top of the box. Mounted on the end of the shaft, outside the box, was a platter, covered with green felt. The record was supposed to spin on this platter, of course. A small lever beside the platter moved a brake into position to keep the platter from spinning while the spring was being wound, or to release it to allow it to turn. Mounted farther down the shaft, inside the box, was an intriguing trio of metal balls. Attached to each ball were two strips of thin, springy metal. The opposite end of each of these springs fitted into a slot in the rim of a metal collar that fitted over the shaft, one collar above and one below the arrangement of balls. These collars kept the balls in orbit around the shaft, suspended by their leaf springs. The lower collar was fixed in position, and the upper one slid on the shaft; however, its movement was restricted by a screw that projected downward from the top of the cabinet, its end against the upper collar. By turning a knob, I could move this screw in its threaded fitting and vary the location of the movable top collar. When the screw was at its lowest setting, the top collar was pushed closer to the fixed bottom collar, and the springy bands were extended outward, pushing the balls into an orbit more distant from the shaft, where their greater angle of momentum slowed its spin and, therefore, the rotation of the platter. When the screw was at its highest setting, the springiness of the metal bands brought the balls inward to a closer orbit and allowed the shaft to spin more quickly, rotating the platter more quickly, just as spinning skaters spin faster with their arms at their sides than with their arms extended. The adjustable orbiting balls acted as a governor, a limiting device. Their original purpose had been to allow the operator to keep the platter spinning at the 78 rpm of old shellac records, so the range of adjustment was kept short, just a narrow band at the center of the machine’s possible range of speeds. The original purpose didn’t interest me, though. I wanted to see the machine spin at its extremes, so I began dismantling the governor.

By removing the adjusting screw entirely, I could make the platter spin much faster than it was ever intended to spin, and by doing away with the trio of balls I could make it spin faster still, quickly enough to catapult small objects from its rim. I tried this for a while, shooting things across the cellar and marking record distances on the floor, but I quickly reached the catapult’s practical limits, and the record player vibrated so violently that it seemed likely to shake itself to death, so I gave that up.

More intriguing was the opposite extreme. With longer screws I could slow the machine down. When I’d inserted the longest screw that would fit, driving the top collar down against the bottom one, I thought for a moment that I’d slowed it as much as could be done, but a little thinking showed me the next step: longer arms, bigger balls. The balls didn’t have to be mounted on the shaft, I learned; they could be mounted on the platter and they’d accomplish the same thing! It was the work of a happy hour to attach three dowels to the platter, each with a rubber ball at its far end. The system wasn’t very well balanced, but it turned with majestic slowness, the balls bobbing gently as they orbited the center. The whole arrangement reminded me of the electrified model of the solar system kept in a glass case in the hallway of the oldest of the elementary schools in town. The school board had spent quite a lot of money to buy this model solar system and, fearing that use would wear it out, limited its public appearances to an annual demonstration before an assembly of students in the school auditorium, when we actually got to see the creaking mechanism turn. At the center, symbolizing the sun, was a naked light bulb. That, I saw, was what my gadget needed—a light.

I thought of trying a small table lamp, but my mother spotted me sneaking it out of the living room, so I had to settle for a flashlight. I taped the flashlight to the platter, wound the motor, and released the brake. Watching the spot of light moving around the walls of the darkened cellar, I realized that I had here the essentials of a lighthouse. I had wanted a lighthouse of my own for years. Now I was halfway there. I had the mechanism. All I needed was the shell, the housing, the lighthouse equivalent of the record player’s cabinet. That couldn’t be hard to come up with. Next to what I had already accomplished, it ought to be a snap. I didn’t see any reason why, with some help, I couldn’t build a lighthouse in the back yard in a couple of days. Of course, I would need my father’s permission.

[to be continued]

In Topical Guide 571, Mark Dorset considers Gadgets: Mechanical: Orrery from this episode.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, and Reservations Recommended.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post