6

WHEN SCHOOL OPENED, I entered the building through the front door with all the other students and immediately felt a great loss. The building was now available to just about anyone. Its hallways rang with the clatter and din of a vulgar horde—a vulgar horde composed largely of my friends, it’s true, but they seemed like invaders nonetheless. The invaders wore looks of bewilderment, just like the look (I imagined with a mental sneer) that the foot soldiers of Alaric the Visigoth must have worn when they entered Rome. Merging with the rushing confusion, I caught sight of myself reflected in the glass of a door. I was surprised to find that I wore the same look. None of us knew it yet, but we were all going to be wearing that look for some time. There were four reasons—at least four reasons—why.

First, at some time during the summer we must have passed a boundary between childhood and adolescence, without even noticing it. I had had some vague realization of this as soon as I entered this new and larger school building. I felt that I was suddenly expected to be, in some way that I did not understand, newer and larger myself, more grown-up, more responsible. That was unsettling enough in itself, I’m sure, but time’s longer view shows me now that it was compounded by the fact that when I looked for models of the grown-up and responsible behavior that the seventh grade was apparently going to require of me, I looked, more closely than ever before, at my parents, and I began to come to see—again, only vaguely—that they were imperfect models, quite possibly unequal to the puzzling demands of the seventh grade.

Second, I discovered to my surprise that the kids of Babbington came in a far broader range of shades of beige and brown than I had previously realized. I had known birches—and ashes and oaks—but now, in that instant when I came through the front door of the new building, the range was extended to include boys and girls of teak and mahogany and walnut. Here was a bunch of my contemporaries whom I’d never seen before. Where had these browner boys and girls been all this time? I think I realized—I think we all realized, at some level below words—what this surprising broadening meant: there was more to Babbington than we knew. Immediately, the unsettling question arose: how much more? How do we measure the size of our ignorance, after all? We don’t know how much we don’t know until what we don’t know becomes what we didn’t know; that is, after we know it; and then we know only how much we didn’t know compared to what we know now—we still don’t know how much we don’t know. This was the first lesson of the seventh grade, taught the moment I came through the door. It might as well have been chiseled into the terrazzo that had been so thoroughly cleaned and polished for opening day.

Before that moment, I suppose I thought, if I thought about it at all, that I had Babbington pretty well figured out. Now here was new evidence of my ignorance. Sometimes my youth seems to have been devoted entirely to the accumulation of such evidence. Here was the revelation of a new world. I felt disoriented, much as I imagine a fifteenth-century peasant would have felt if he’d been handed a map at the center of which was something other than his little village, the center of his world. I remember well another feeling that came with this new knowledge. I was annoyed. I didn’t like the idea that I had been kept in the dark or the notion that I was now expected to make sense of this larger world on my own. It seemed a lot to ask of a kid my age. I had begun kindergarten before I turned five and had skipped the third grade, so I was only ten-going-on-eleven. Perhaps, I asked myself, it would be possible to take another shot at the sixth grade and confront these puzzles next year, when I had matured? Not likely.

[to be continued]

In Topical Guide 577, Mark Dorset considers Segregation, Racial from this episode.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

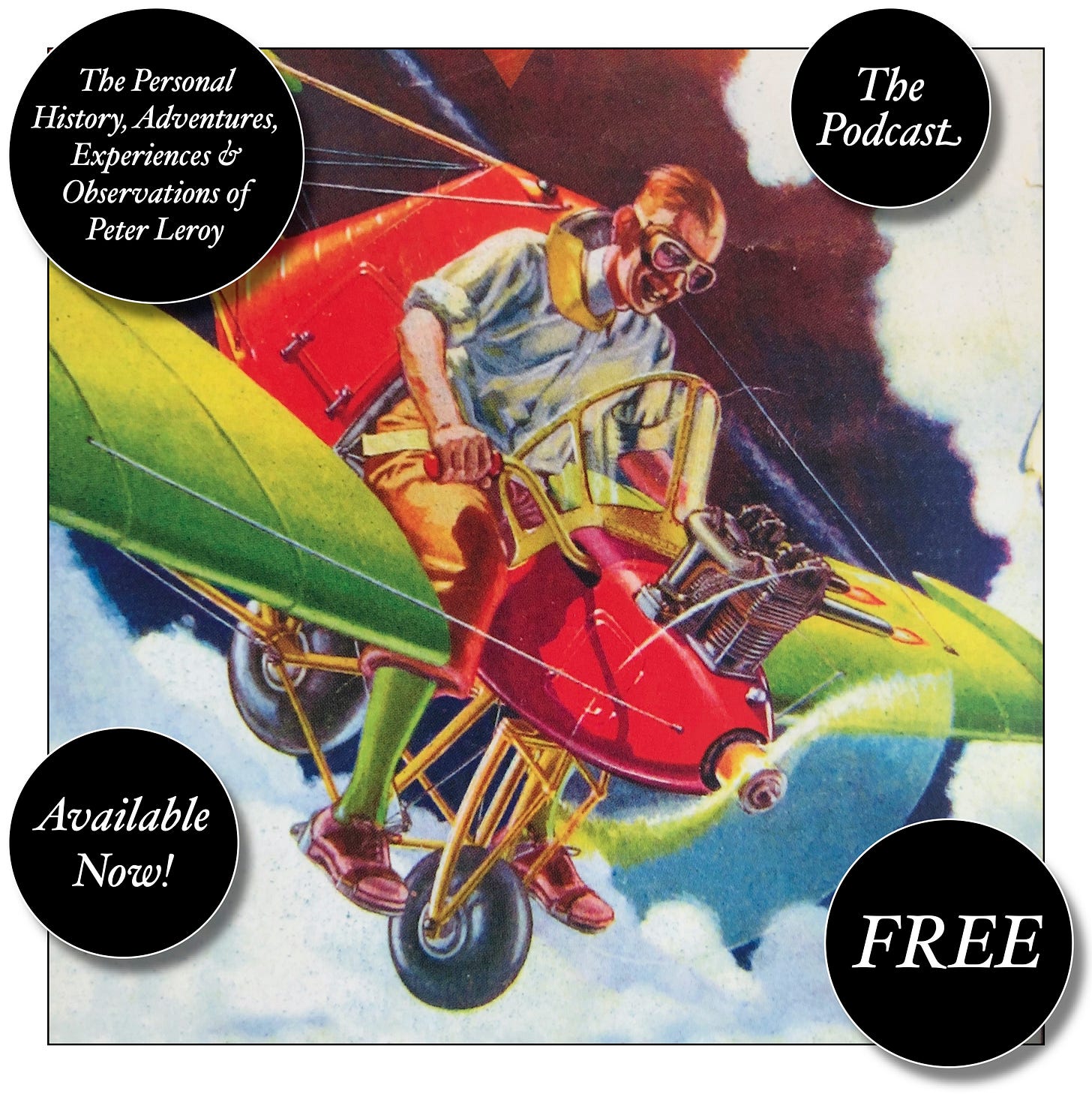

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, and Reservations Recommended.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.