THEN THE LODKOCHNIKOVS got a television set, and the center of my attention shifted at a stroke—not to the television set, but to Ariane’s hip.

The Lodkochnikovs lived in a house on stilts at the very edge of the estuarial stretch of the Bolotomy River. They had gone without television longer than any other family I knew. My own parents had been holdouts, too. They had resisted long enough for me to begin to feel a little ashamed of showing up at neighbors’ houses whenever a favorite program happened to be coming on, trying to seem ignorant of the schedule but always showing up just before the hour or the half hour. Since food, as the token of hospitality, must be offered even to the least of guests, I was served a lot of meals and snacks in those neighbors’ houses, and politeness required that I eat them. I began to feel indebted and burdened by my debt. My friendships had begun to suffer from the feeling, so I was greatly relieved when my parents finally bought a set and I could stay at home, watch the programs I chose, and eat the snacks I favored. The Lodkochnikovs went without television for much, much longer. Year after year, despite the pleas of his wife and children, Mr. Lodkochnikov held out. He was just against it, he said. Then one day something snapped in him, and he came home with an antiquated set, a tiny screen in an enormous box. The family was dumbstruck. What, they wondered, could have brought about this change of heart? He never offered any explanation, and the others were wise enough not to press him for one. Some unknown, unexpected something had changed his mind—who cared what? Well, I did. It puzzled me.

He installed the set in a small, dark room at one end of the house, formerly used as a storeroom. Ariane and her mother cleaned it enthusiastically in anticipation of the arrival of the set, but the room still held the musty odor of a closed room, of neglect. That end of the house hung well out over the river, so at low tide the musty odor was augmented by the odor that permeated the entire Lodkochnikov house at low tide, the smell of Bolotomy River muck. They furnished the room with scavenged furniture: a couple of kitchen chairs, their seats and backs padded and covered with red plastic patterned to look like marble; two chairs with maple arms wide enough to invite you to rest your glass on them and curved enough to make it likely that the glass would slip, spill, and earn you a smack from Mr. Lodkochnikov; and, most important to my story, an enormous old sofa, each cushion sagging to a different level, originally upholstered in mud brown, but now covered with a couple of chenille bedspreads that Mrs. Lodkochnikov had sewn together and tucked and tacked and pinned to the frame. This slipcover I associated from the very first—guiltily, thrillingly—with bed and with Ariane and with Ariane in bed, because there was a chenille bedspread on my bed at home, and because if I dropped in at the Lodkochnikovs’ before noon on a Saturday I sometimes caught a glimpse of Ariane wearing a white chenille robe. I made a practice of dropping in on Saturday mornings in the hope of catching such a glimpse. When I did, it pleased me to believe that under the white chenille robe she was wearing nothing.

I remember well that first night of television at the Lodkochnikovs’. Mr. Lodkochnikov sat proprietarily in the more upright of the maple chairs, smoking a cigar and drinking beer while he watched, commenting continually on what he saw, sometimes just murmuring an objection, sometimes anticipating the punch lines of the jokes, sometimes grumbling, sometimes just snorting. At some point in the evening I became aware that his attitude toward his television set had changed from pride to disappointment. I wish I’d been aware of the change earlier, when it began, so that I might have noticed and reported the process. It must have been gradual. If my senses, sensors, or sensibilities had been more refined, I could probably have detected it early on. There must have been signs—a certain twist of the mouth, the slightest lethargy in the way he knocked the ash from his cigar, measurably longer pulls at his beer bottle—but I didn’t notice them. I saw the difference only when it became gross enough to be an obvious contrast to his earlier state, so it seemed to be something sudden and discontinuous, like one of Quanto’s or Miss Rheingold’s startling leaps.

Finally, he got up with a grunt and left the room. To tell the truth, the rest of us were glad to see him go. He’d become pretty vocal as his disappointment had grown, and by the time he left, his grumbling and snorting were even drowning out the commercials. We were happy to be alone and silent, sitting in the silver glow.

New television sets had been coming onto the market quickly for years, each new model offering advantages over the earlier ones—a larger screen, better sound, and so on, and people were quick to replace one set with a newer one. Mr. Lodkochnikov, through a network of contacts mysterious to me then but which I now think must have been based entirely on barroom encounters, had easy access to outmoded sets at the discounted prices of superseded technology. That very first evening, when he left the room in disappointment, he launched a hobby: he began a quest for the perfect television set. For a while there was a different set in the little room every time I visited. Now and then Mr. Lodkochnikov himself would come into the room and sit in the upright maple chair and watch his latest set for a while. His older sons, the two Ernies, would try to anticipate his comments about the shows and make them before he could, in voices low enough so that he wouldn’t realize they were making fun of him. They didn’t have to be particularly careful, though, because Mr. Lodkochnikov’s fascination and annoyance with television ran so deep that he was oblivious to everything else while he watched. However, each time he gave television another chance, at some point, inevitably, the moment would come when he’d had enough; he would grunt, get up, and go off, disappointed again, and soon he would replace the set with a different one. Apparently what other people said about watching television had led him to expect more. He gave each set a fair trial, and when he didn’t find what he expected, he went out and got another. He was trying to buy a set that didn’t exist: one that got better programs.

For Raskol and me and the two Ernies and Mrs. Lodkochnikov and Ariane, this was not a problem. For us, there was lots worth watching, or, to be more accurate and honest, anything was worth watching. This was a time when the medium still fascinated people for itself. Just the idea of sitting in a room in your home and watching a little gray moving picture was a pleasure of its own, no matter what the show was, and certainly without regard to what its quality was. Whether the show was good or bad only partly determined whether the experience of watching it was good or bad. We weren’t watching a show on television, we were watching television itself.

[to be continued on Monday, November 27, 2023]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

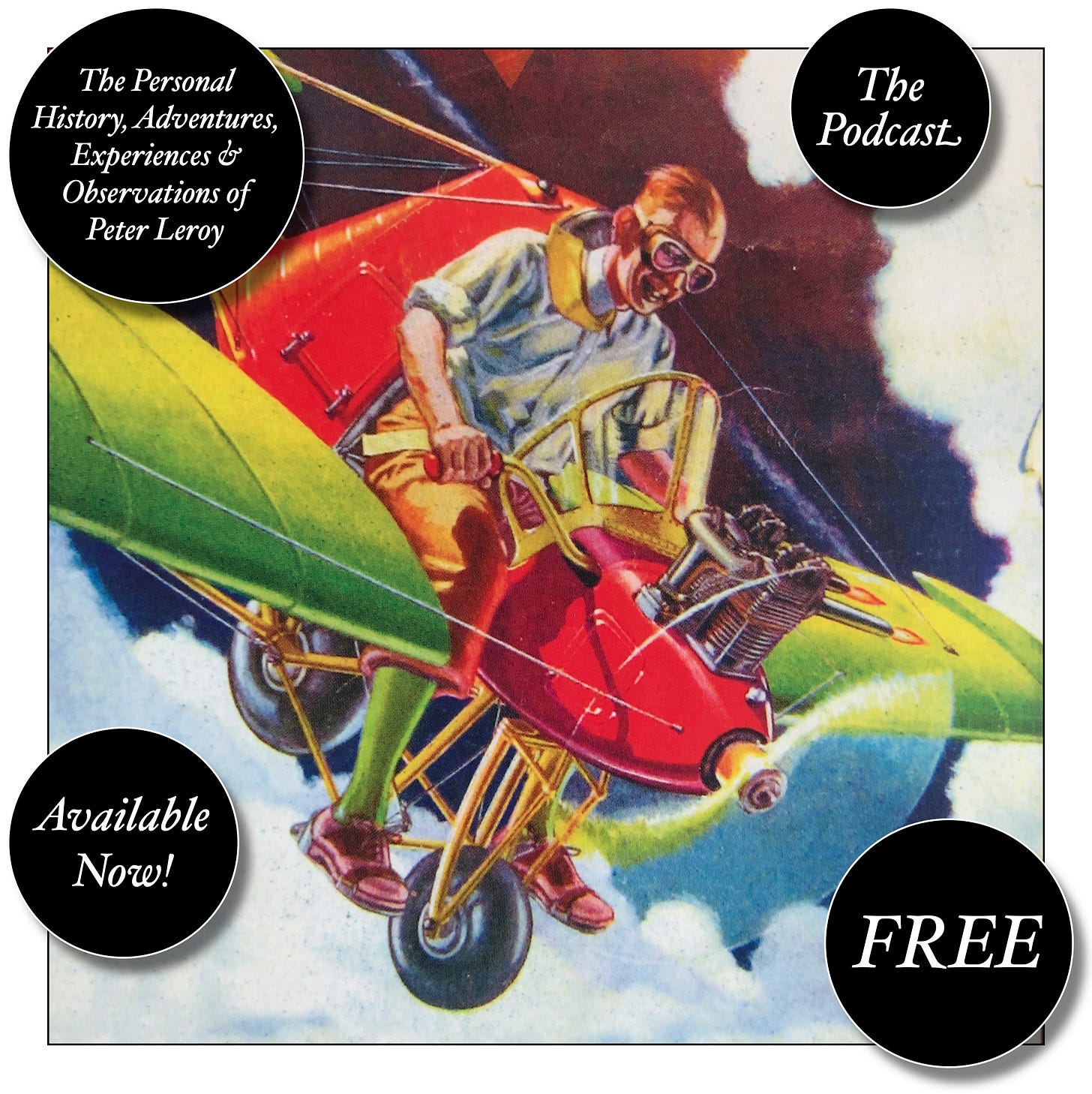

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, and Reservations Recommended.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.