WHEN DENNIS, the young man everyone called “Denny,” went to Corinne’s that night, he didn’t intend to stay. He came to take Ariane away.

“There’s a party,” he said. “The ‘kids’—”

“My old school chums,” said Ariane, with enough of a trace of a sneer so that he’d notice, but not so much that he’d be annoyed.

“They’re having a party—and I wondered if you would come along.” Now he was actually holding his hat in his hands. In another moment, he’d be stammering. “I wanted to see my old friends, and they’re sure to be there, and it’s been so long that I really would like to catch up on what they’ve been doing, you know, and it ought to be fun, and—well—would you?”

She accepted Denny’s invitation to the party, although she considered herself a little old for these parties. She was nearly twenty, after all, and had been out of high school for two years, and although many of the “kids” who gathered at these parties were three or four years older than Ariane, she considered them terribly immature. The parties were a tradition several years old, begun by the class a couple of years ahead of Ariane’s, a particularly close-knit group who had fallen into the habit of holding parties every weekend, starting the weekend of graduation, to keep the group from drifting apart. Without apparent planning, as if there were merely a gravitational accretion, like the agglomeration of dust that makes a star, kids (and they still called themselves kids) gathered at someone’s house, bringing beer, food, and records. After a couple of years, the idea had grown stale for the original kids, and the gatherings had gotten smaller, as kids drifted away to other towns, into marriage, to New York, to Korea, and as some of them ceased to think of themselves as kids, but new graduates, from more recent classes, began showing up, and the tradition renewed itself (and went on renewing itself, so that, in Babbington, it continues still, a tradition of intergenerational whoopee that I haven’t seen elsewhere). Although the group now seemed a little young to Ariane, some of the original kids still showed up at every gathering, out of habit, and the habit breathed with fresh vitality when one of their group returned from Korea or when news of a death circulated among them. On momentous occasions like that, even the old kids who rarely put in an appearance returned to the group to say hello or good-bye, to slip into beery nostalgia and wax sentimental over those palmy days a year or two ago. The return of Denny counted as a momentous occasion, so there was sure to be a good turnout among the older bunch, and Ariane could use the opportunity to begin transforming herself from town slut into someone else.

“I might have to change,” she said, meaning her clothes.

With her mind’s eye she looked into her closet and found that she had nothing to wear. That is, she had another clam-bar outfit, just like the one she was wearing, and she had two dozen Tootsie Koochikov getups. For a moment, she thought of wearing her favorite: a tight black skirt and a fuzzy pink sweater, but she knew that wouldn’t change a thing.

“Change?” said Denny. “What for? You look cute just the way you are.”

“Cute?” Cute was not a Tootsie Koochikov look.

“Yeah,” said Denny. “Cute as a button.”

So she went as she was, not as Tootsie Koochikov, but as the cute kid from Captain White’s, in the cute outfit with the little flippy skirt and the saddle shoes. The other kids regarded her with amusement, which, to their credit, they tried to hide, but on a couple of faces she caught looks that made her wiggle her head just a little to make sure that she hadn’t left her clam hat on.

Denny, just back from Korea, played the part of the local hero. He was standing at the center of a bunch of lionizing friends, and Ariane watched for a moment from a distance, to examine her feelings before she moved in among the rest of his audience. She found that she was attracted to him, and that she liked the way he held everyone’s attention. Most of the other boys were wearing black pegged pants, but Denny was wearing slacks and a sports jacket, a shirt with the collar open, the points of the collar spread over the lapels of his jacket. She found herself wondering how deliberately he had chosen this outfit, whether he had considered it as she considered her clothes and had chosen it specifically to set himself apart, to show that he was a man. She joined the group and listened to his stories. The war was long over, and Denny’s time away from home had been little more than long days of dull routine, but he told a story well and he had a sense of the drama of the possible and the tension he could get by balancing hope against fear. Also, like many another timid soul, he had a fondness for blood and guts. Since he had had no war to give him hell, he had had to invent it. In his stories buddies shot one another accidentally on the rifle range or in darkness on what he called “the line,” a half-track crushed a dozing lieutenant into a mess of blood and jagged bones that Denny recalled from the day his dog was run over, a brawl in an off-limits bar that he had never visited left a finger on the floor that went unclaimed, and after an argument over a pinup picture a section of his best buddy’s cheek was left dangling, dripping blood, “just like a slice of rare roast beef.” He was especially proud of this last detail, which he told with a carving motion, because he had invented it from scratch—in this case from a scratch an acquaintance of his had suffered when he fell off a bar stool. Ariane drifted away. This stuff didn’t interest her. She had heard enough of it from her bellicose brothers.

An hour later, she was bored. Nothing special was happening. She was standing just outside the kitchen, leaning against the dining room wall, holding a can of beer in her hand. Denny was standing beside her. He was shy with her, too reticent to reach out and take her hand, though he wanted to. He just stood there, twisting his beer can in his hand, all his stories spent, trying to think of something to say. Ariane stood there beside him, wishing that she were somewhere else and gradually coming to realize that she had been wishing that she were somewhere else for about four years, almost steadily. She was looking straight ahead, at nothing. She didn’t drink her beer, just held the can.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

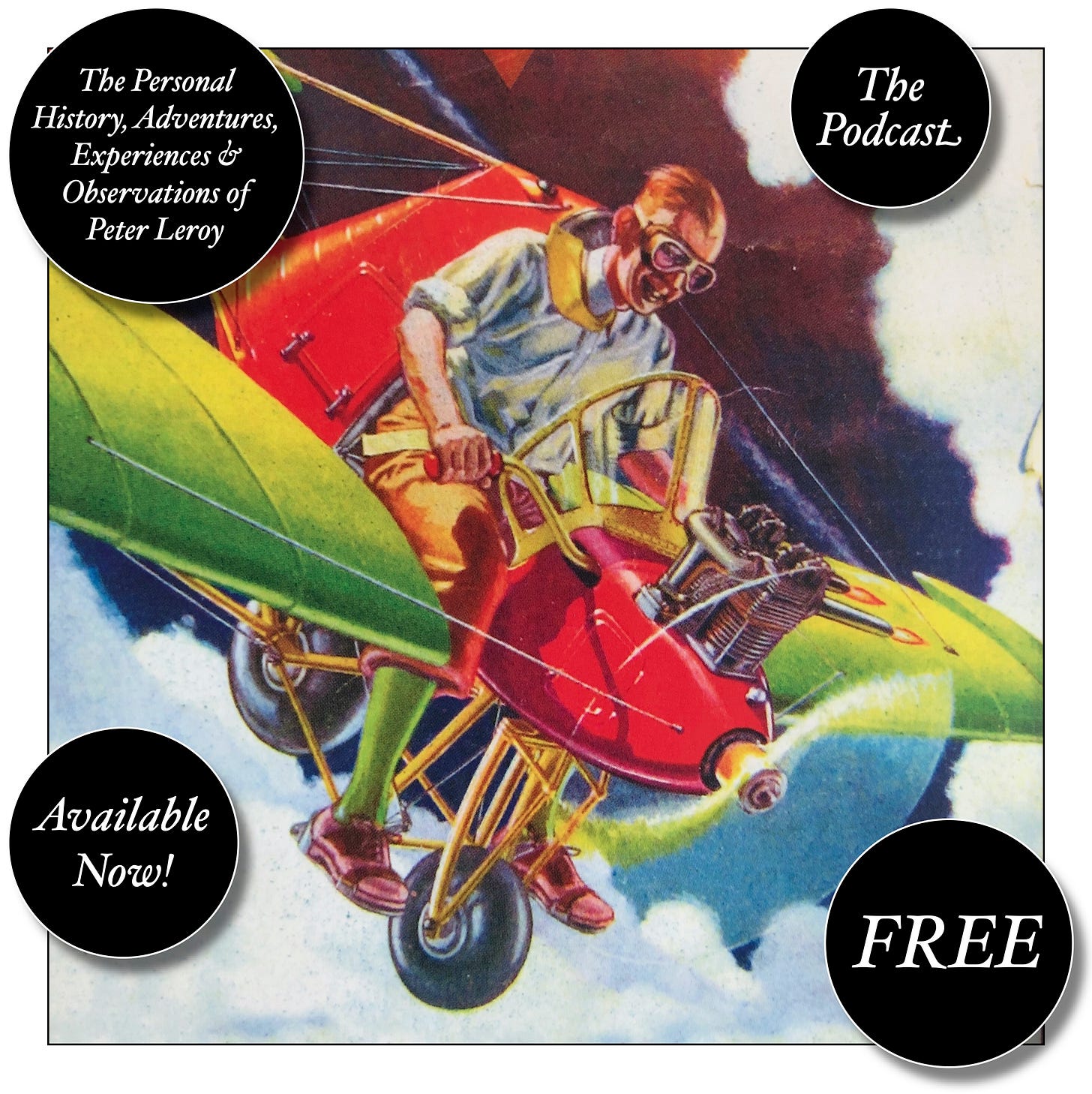

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post