25

“WHEN I TOLD HIM, he was—just—incredulous. That amazed me. Did he really think he had hidden the stuff so well? He just couldn’t believe that I’d found it. Then he was offended. That didn’t really surprise me. The guilty ones are always offended—or pretend to be offended.”

“ ‘You’re accusing me? I can’t believe this. After all I’ve done for you, how could you suspect me of something like this?’ ”

“You’ve got it. But try, ‘after all we’ve meant to each other.’ ”

“Oh. Sure.”

“But most of all, he was crestfallen. I didn’t realize this at the time, to my eventual dismay, but I had made him feel ashamed—but not for what he’d done. For being discovered. I had diminished him, made him feel small—”

“—like a child on the edge of adolescence who dreams adult dreams and ventures into adult company and is greeted by the pet name his mother gave him in the crib—”

“—I had taken the wind out of his sails—”

“—taken the lead out of his pencil.”

GUY BEGAN GLANCING around the room, trying not to move his head, trying not to give away any hiding places that Ariane might not have discovered, but trying to determine what had been disturbed, where she had looked.

“You found it?” he cried.

“Yes,” she said. “I told you.”

“What do you mean by that?” he asked, brightening. “You ‘found it.’ Just what did you find?”

Ariane could tell what was going through his mind. He was beginning to think that perhaps she had only discovered the poorest of his hiding places. The thought struck her that for the time being, for this moment, right now, nothing else in the whole affair mattered so much to him as the fact that his hiding places hadn’t worked.

“I mean that I found everything,” she said simply, without trying to put a face on it, without any effort to hide her disappointment in him, or what was beginning to feel like disgust. She lifted the lamp from his bedside table, reached under it, and pulled out a wad of tissue that held a pair of onyx cuff links. She dangled the tissue pouch in front of him. She tried not to sneer.

“The cuff links, you mean,” he said. “You found the cuff links.”

“Yes, I found the cuff links.”

“Well—”

She pulled the drawer out of the bedside table, completely out, and turned it toward him so that he could see the back end of it and know that she had found what was taped there, an envelope with small bills in it.

“And you found some money,” he said. He seemed to be trying to look smug, and Ariane resented it. He was playing with her, as he would with a child, as if they were whiling away a rainy afternoon, playing “hot and cold” or “hide and seek.”

“I mean,” she said, in a measured voice that she intended to end the notion of playing around, “that I found all of it. Everything.”

“Prove it.”

“Oh, come on, Guy.”

“No, I mean it. You say you found ‘everything.’ I’d like to see you prove it.”

She was stunned. She was also beginning to understand that he had been wounded. She could see the pain in his expression, and she saw an odd dispassion, a hollowness in his eyes—but still she didn’t see any danger.

She should have: the shadows of the venetian blinds fell at a slant across the bed, making a set of sharp diagonals that disturbed the rumpled softness of the covers, and Guy had risen from the bed and was standing beside it, so that she was now looking up at him from below, at the dark hollows of his eyes, the stern set of his chin, the nasty, challenging twist of his mouth. This was not tranquility by design.

“Don’t be silly,” she said. “This isn’t a game. I think we ought to talk about what—”

“I don’t believe you,” said Guy. “I don’t believe you found anything more than some cuff links and a few bills.”

A profound disbelief passed through her, leaving her feeling empty, hollow as the look in his eyes, as if it were impossible or useless to think, as if mechanical action were all she could manage, all that was required.

“All right,” she said, and she began to go about the room, pulling out the bundles of cash she had found and the pieces of jewelry: the pearl bracelet, a ring, a pin, a wristwatch, and as she collected them he watched in silence. They amounted to no more than two dozen pieces in all. One pair of earrings was mismatched. She tossed each item onto the bed as she retrieved it. “There,” she said, when she was done. She couldn’t have disguised the contempt in her voice if she had tried.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

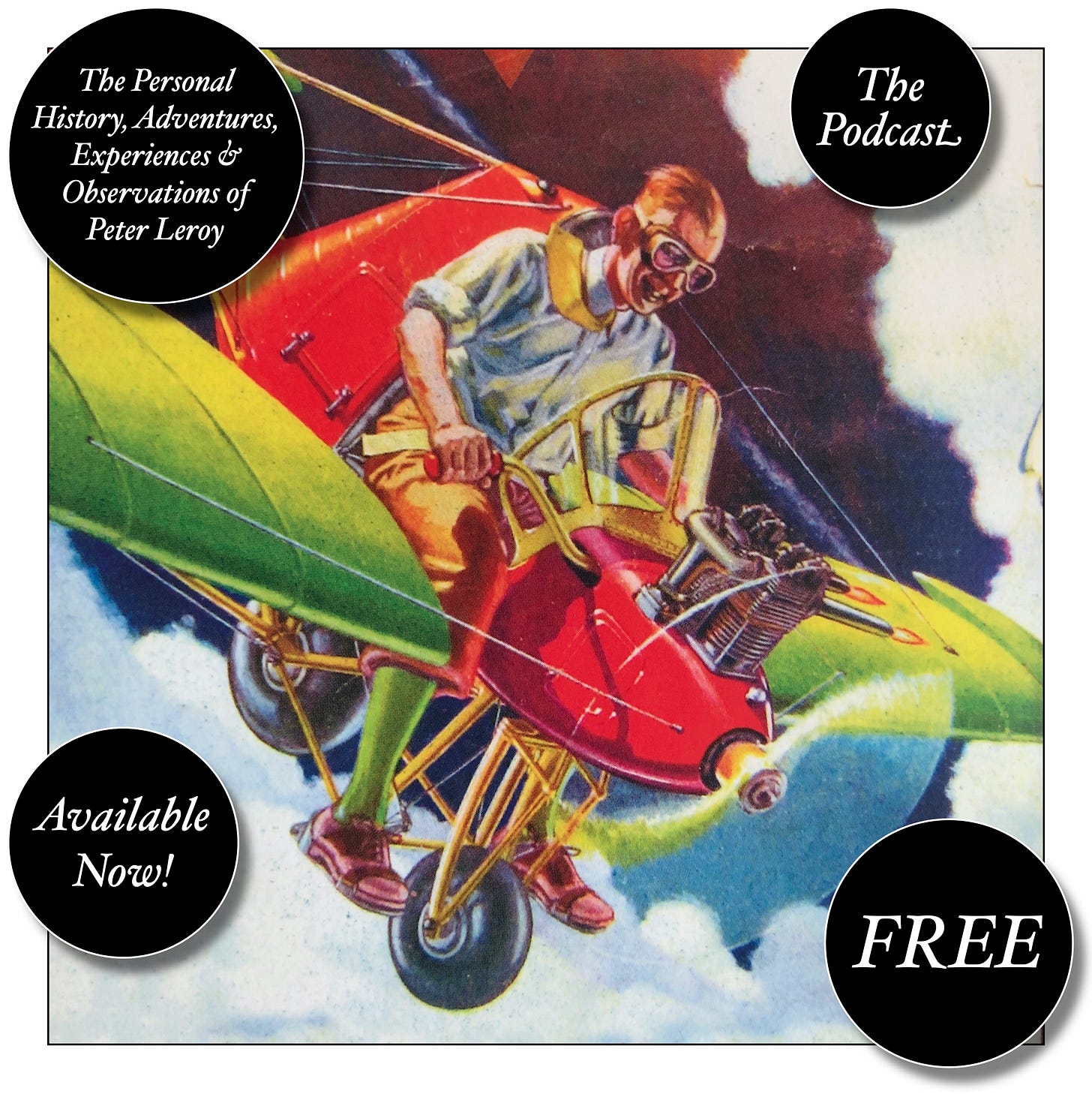

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post