31

ONE NIGHT, my grandfather was sitting at his usual place, the small round table in the back. It was not a pleasant night. He had come through the rain for his usual couple of drinks. Two or three of the “boys” at the bar had made their ritual trips back to his table to see how he was doing and ask how Eleanor was getting along. They all knew Jack Leroy, and they all knew that Eleanor was ill. “Sick,” they said, and in a mumble they would add “fatal,” but they wouldn’t say “cancer,” because they were unconscious believers in the power of words, their magic, and their dangers.

In certain more or less overlapping circles of Babbington, everyone knew that my grandmother was dying. The details might be different—or differently understood—from circle to circle and house to house, but a large part of the population of the town, especially the older part of town, south of the highway, knew the ultimate truth, and that knowledge made them humble, inarticulate, in some cases even mute, when they were around my grandfather. They usually asked after my grandmother, but in barely audible voices, with their eyes down, sometimes with their heads bent, worshipers in the house of death. What they asked required only a ritual response, so it wasn’t important or even necessary for my grandfather to know just what they were asking, only that they were asking.

This deference paid to Grandfather was universal among the men who worked the bay. For many it was, I suppose, deference paid to death rather than to Grandfather. These men respected death, and perhaps in a sense even revered it, in a way that they did not respect or revere life. They would mock life, risk it, and take it—from fish, eels, clams, ducks, the runts of their dogs’ litters—but death made them humble, and death made them mumble. They understood that they had some power over life, but no power at all in the face of death. They didn’t know what to say when confronted by it. Who does?

“How’s it going, John?” asked a short gray man with a broad belly.

It was the clamdigger known as Bitzer, a grizzled old-timer, making his trip to Grandfather’s table, paying his respects, doing his duty.

My grandfather looked up, puzzled for a moment by the sound of “John” from Bitzer. Grandfather had been “Jack” to everyone when he worked the bay as a boy; he was Jack to all the adults in the family; he was Jack to my grandmother, and he had always been Jack to his buddies among the baymen when he stopped in to “see Red” at Corinne’s of an evening, but in his troubles he had become John. He nodded to Bitzer, as he nodded to all of them, putting a manly face on it, and made a grimace—his grim grin. It was all the acknowledgment he would make of the hard truth, the depth of his care and woe.

(I remember well that look on his face, that grim grin. It was I who called it his grim grin. I was just a boy, too young to understand it. “Grampa Jack,” I said, one day, before I had been inducted into the ranks of those who knew that my grandmother was dying, “that’s some look you’re wearing. That’s a grim grin.” I was at an age when I thought I might be clever. My grandfather was a forgiving man, with an astonishing depth of understanding. He turned the grim grin into something very close to a normal grin and gave it to me the way a person sitting in the front row of a theater during a bad performance might give the cast a laugh just to help them get through the rest of the night.)

“She feeling all right?” asked Bitzer.

Only the boldest of them would ask anything like that. When they did, they expected the kind of answer that would reward them for having asked after her, without subjecting them to having to know how she actually felt, and Grandfather knew that, so the kind of answer they expected was the kind of answer he gave. It wouldn’t have done, wouldn’t have done at all, in the etiquette that obtained among these rough men, for Grandfather to say that she was worse, that she was fading fast, that she was thin and getting thinner, that at times she seemed confused, distant, hopeless. To answer with the truth would almost have seemed like a reproach for their having asked, for their having done the neighborly thing, the fellow-feeling thing.

So Grandfather said, “Hanging on.”

Bitzer gave a nod, just a single nod of the head, and looked down at the floor.

“Hanging on,” Grandfather repeated. He made his grim grin.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

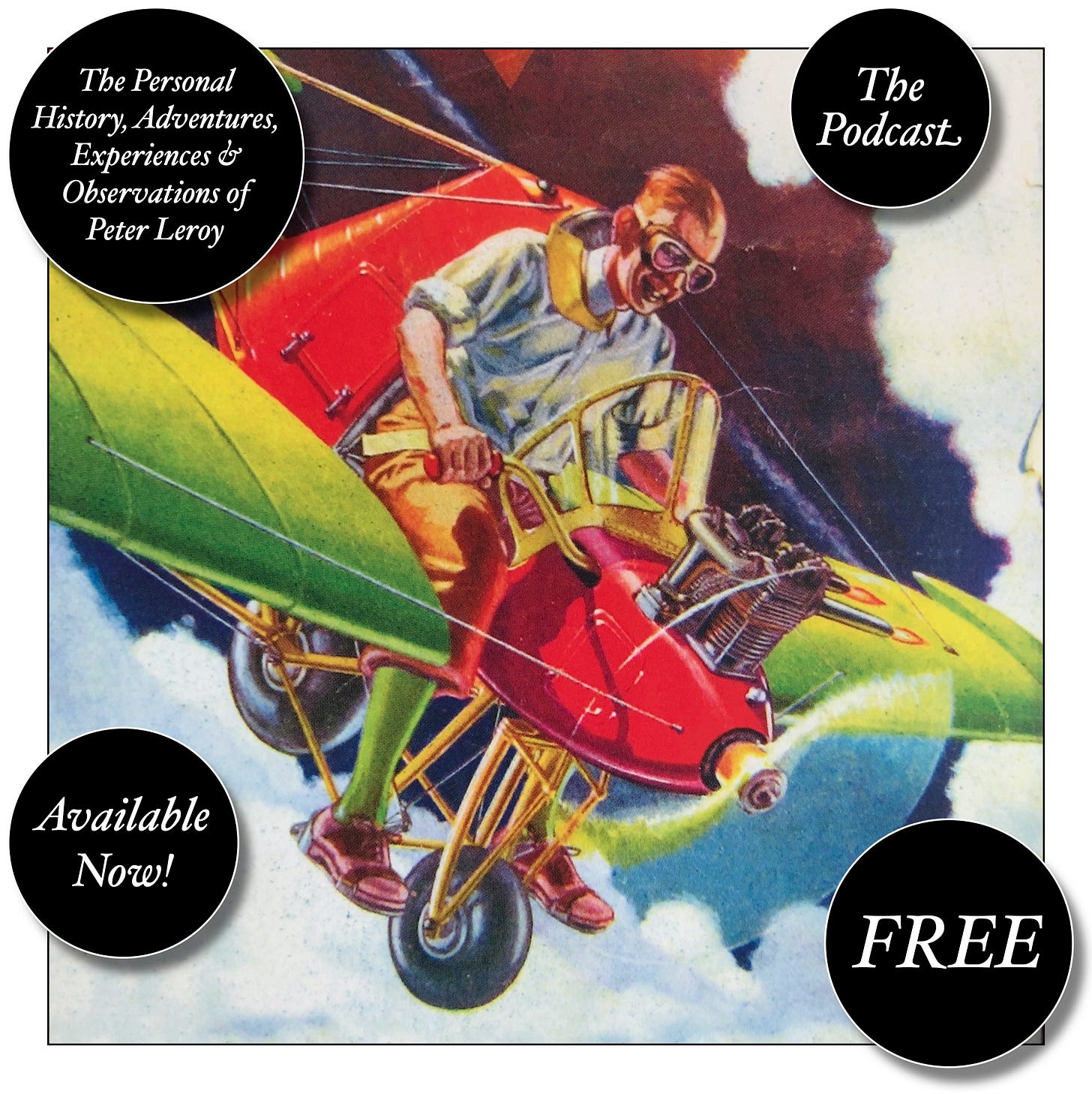

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post