37

“THERE WAS A LOT OF WORK to be done,” she said, “and I threw myself right into it. If you think about it in terms of being on a boat—and I did think of it in those terms—I wasn’t really the first mate. I was the cook, and a deck hand, and the navigator—sort of—you’ll see—and also the boy—”

“—the young landlubber who runs away to sea and will do whatever dirty job gets thrown his way, just for the thrill of being on board and underway.”

We were in her living room, but in her eyes I saw the faraway look of someone standing on a deck at night. “I suppose John thought of me as a volunteer maid—or something like that.” A smile crept over her face. “But in my mind I had signed on,” she said. “I thought of myself as the first mate.”

IT WAS ARIANE’S FIRST evening on board. My grandfather came out onto the porch and closed the door behind him. Ariane was waiting down at the west end, at the farthest point from my grandparents’ bedroom. She was sitting on the wicker love seat there, with her legs folded under her. She was bent over the round wicker table, where she had spread the charts that Grandfather had given her. She had brought with her an atlas and a composition book (a relic of her school days, from which she had torn the used pages—an essay on the Federalist Papers, a composition entitled “Will We Ever Have a Woman President?” and a list of things to do before graduation). She had found an ashtray in the kitchen. She was smoking a cigarette. When my grandfather was close enough to hear her whisper, she whispered, “So, where are we?”

My grandfather looked puzzled. He might have been uncertain about whether he had heard her correctly; his hearing was going.

“I mean how far have we gone on this voyage?” Ariane said.

“Oh,” said Grandfather. “Well, we’re past Cuba, on our way to the Panama Canal.” He looked at the floor and frowned. He couldn’t help feeling foolish. “Look, Ariane,” he said, “maybe—”

“John,” said Ariane. She may have touched him, may have put her hand on his arm, or she may only have looked at him; a certain kind of look is touch enough. “You don’t have to feel foolish about this.”

“How did you know I did?”

“I know because I used to have an imaginary girlfriend—you know, an imaginary playmate—”

“Lots of kids do,” said Grandfather.

The fact suddenly struck him that the young woman on his porch, sitting on his loveseat, looking up at him with such eager eyes, was awfully pretty. (It must have struck him at some point, and this point is as likely as any other.)

“Sure,” said Ariane. “I’ll bet most people have had an imaginary playmate, but even so, grown-ups act as if they never did. You know?”

She rearranged herself on the love seat, unfolded her legs. My grandfather must have noticed those legs. I had studied them myself.

“Yes, I know,” he said. He chuckled. Perhaps he was recalling his own imaginary playmate. He was loosening up. Ariane smiled, and he sat down. It was the first evening in a long time when he had thought about anything but my grandmother.

“Well,” said Ariane, “I hung on to my imaginary playmate a little too long, you know? People began to worry about me. I was old enough to understand that I was supposed to be too old for her. And I saw the way people looked down on me for hanging on to her, for having her as a friend. I remember the way they looked at me, that smile.”

She gave him an example of the indulgent, tolerant, accusatory, and dismissive smile worn so often by people who think that the life of the mind is not the same as real life, and that the thoughts of children are childish. (I’ve had that smile turned on me sometimes, since the people who use it are often the same ones who think that a serious thought ought to wear a serious face, and I—since I am, like my grandfather, the maker of a fantasy—often find it difficult, as he did, to keep myself from feeling foolish. How dare I, after all, issue a denial of the way things really were? There is that suspicion that people will consider me nothing but an escapist, or a liar, or a child, and turn on me that condescending smile.)

Ariane stuck her tongue through the nasty smile, destroying it, and gave Grandfather a real one and a wink. (And she must certainly have touched him then. Maybe he even touched her. I don’t know.)

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

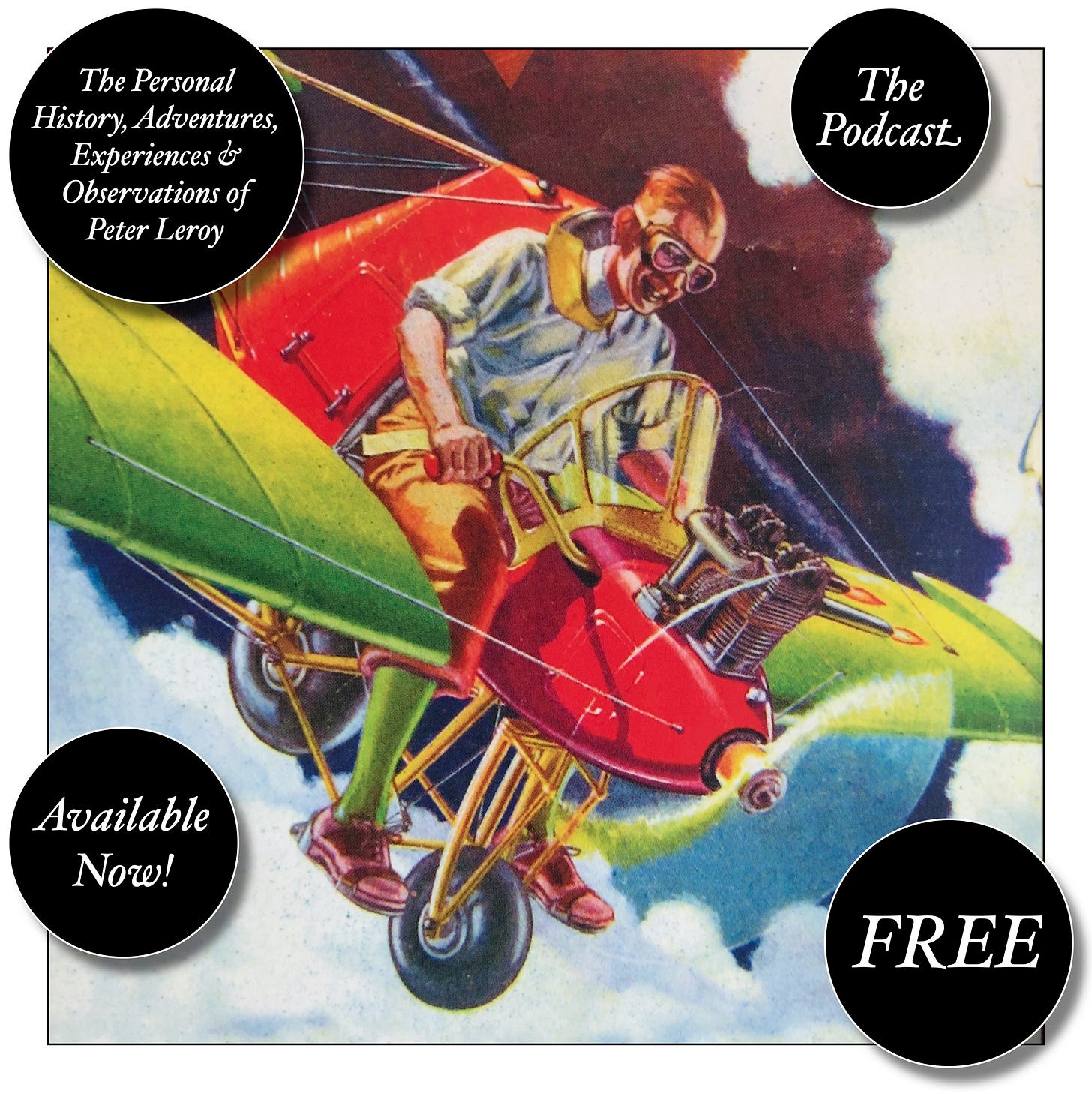

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.