45

FROM The Films of Gregory Tschudin, by Andrew Cargill:

To Rarotonga

At first this tense little exercise seems like nothing more than a twisted kind of homage to the windswept terror of Wuthering Heights and its cinematic offspring, improved by a spectacular seaside setting and by a couple of coy scenes in which Stan Hunt and the zaftig Darlene Snell romp naked in the surf, scenes notable for the fact that Hunt and Snell manage to fling themselves about with apparent abandon without, however, revealing a single interesting anatomical detail. (What a very long time ago it seems when the bodies of screen sirens were sculpted mainly by our own wishful thinking. O tempora! O mores!) The film is saved, and indeed is elevated to the stature of a minor classic, by a stunning performance from Miss Snell, a clever plot twist (which made contemporary audiences gasp and spawned a dozen variations), and what may be Tschudin’s finest work as a director.

In its first half, the story seems to develop as a sentimental tale about a mercy killing. Hunt plays Daniel Corbett, a fortyish industrialist who has largely retired from business to care for his ailing wife, Theresa (Angela Corliss, who looks as frail and pale as porcelain). Miss Snell plays Diane Farrell, a private nurse who answers an ad placed by Theresa’s father, Edson Turner (Edward Bennet Jones). Turner is a tall, gaunt, grandfatherly type who lives in a looming granite pile, with (I swear) turrets and battlements with crenels and merlons. A broad lawn sweeps down to a bluff. Here the ailing Theresa has been brought, one feels, not to recover, but to die. Diane’s interview takes place at the very edge of the bluff, where Turner likes to take his afternoon tea. His daughter is dying, he explains. (We never do know exactly what ails her, but judging from the symptoms, it seems to be terminal languor.) Throughout the interview, the surf beats continually against the rocks below, so loudly sometimes that Diane has to lean across the table to make out what the soft-spoken old coot is saying. Corbett arrives suddenly, his approach muffled by the sound of the surf, surprising and startling Diane. She leaps up, and for a moment, we can imagine her losing her balance and tumbling over the edge of the bluff to the rocks below, but Daniel grabs her with a strong and confident hand and returns her to her seat, murmuring an apology. Their eyes meet. We see compassion and passion in hers, pain and weariness in his.

A kind of weary disappointment comes over the viewer, too, because it all seems so transparent, but this is part of the setup. We predict that the forced intimacy of Diane and Daniel will lead to something more, that Theresa will waste away beautifully, that Turner will dispense pearls of ageless wisdom about the progress of life, that the sea will go on ceaselessly pounding, and that somebody will go over that cliff. We are, as it turns out, right . . . and wrong.

We’re exactly right about the first half of the film, and we could even have predicted the individual scenes: long nights at Theresa’s bedside; hopeful signs of her recovery, disappointing setbacks; Diane’s comforting hand on Daniel’s shoulder, the understanding looks that they exchange; the thoughtful surveillance of the old man, his apparent resignation in the face of death; a reminiscent evening when he recalls his wife, and her death; Diane’s comforting hand on his shoulder; and, scattered here and there, brief flare-ups between Corbett and Turner that seem prompted by something other than the obvious and visible tensions of their circumstances, perhaps by some hidden animosity out of the past, but we can only guess. Soon, as we had expected, there are some steamy scenes on the beach between Diane and Daniel, including those moonlit romps in the surf.

During one of their trysts, Daniel sings to her the old Mills Brothers hit, “Rarotonga,” stretching it out and crooning it, so that it is no longer a silly little novelty number, but something more like a torch song. He confides to Diane his dreams of running off to the South Seas, to kick his shoes off and roam the beaches of—where else?—Rarotonga. Would she like that kind of life? If only . . . ah, but it’s only a dream. We see desire in her eyes, and we see heartlessness in his, but as they leave the beach and make their way up the path to the top of the bluff, we see the old man in the shadows, where he has been watching and listening. In his eyes, as we move in closer, we see fury.

The next morning, Diane is standing in the dining room, pouring herself a glass of juice when Turner rushes in with the news that Daniel has apparently fallen from the bluff “sometime in the night.” Diane melodramatically drops her glass, and in a quick shot of Turner’s eyes we see his glee and know with absolute certainty that he has killed Daniel. At just that moment, Diane looks at him, and she sees it, too. She bends, suddenly, to pick up the broken glass, and cuts herself. At this moment, the film begins to take a turn. Throughout the predictable police business that follows, we can see Diane beginning to scheme and plot.

When she has the run of the house again, she wastes no time. She drugs the old man and ties him to his favorite chair. She lashes poor languishing Theresa to her bed, and for the next few days tortures the pair of them. That’s the only word. She abuses them physically and psychologically, and recites again and again the seductive things Daniel said to her in the moonlight, until they become a mad chant. At one point, Turner offers her money and gives her the combination to the safe. She opens it and removes the money as if she were sleepwalking, and when she has placed four neat piles of bills on the mantel, she walks to the kitchen and returns with a carving knife. In A Little Mischief, Tschudin handled a murder with icy, terrifying detachment, but this film marks the beginning of his affection for the rich red tones of blood. Diane spills buckets. We never see the victims, but their blood spatters and flows everywhere, and their pleading and their cries echo in the mind long after the picture is over. The music that accompanies this carnage is a trio of zither, kazoo, and tin drum, playing that happy little tune, “Rarotonga,” in a clangorous and terrifying style that makes it impossible to hear the tune afterward without feeling your flesh creep.

When Diane has finished her work, she strips and showers. The blood washes from her down the shower drain. It’s a nod to Psycho—or an appropriation from it, but the link between violence and sex in this scene goes far beyond anything in Hitchcock’s film, and at the time of the film’s release sparked a debate about obscenity that seems quaint today. She emerges clean and smiling, dresses in a handsome suit, takes the four neat stacks of bills from the mantel, steps out into the sunlight humming a tune, gets into the car and drives off. Tschudin cuts to a tropical sunset, with palm tree and lagoon. Slowly, the camera pulls back. We see Diane, and in another moment, we realize that she is sitting in front of a travel poster. She seems catatonic. There is a faraway look in her eyes. In another moment, we realize that she is in a cell. According to Tschudin, this was not at all the ending he had wanted. The original version actually ended with Diane soaking up the sun on an island beach, but it tested badly. (That’s putting it mildly. The audience was outraged. Again, this reaction seems ludicrous in light of today’s bloodbaths and outlaw heroes, but ’twas so.)

[to be continued]

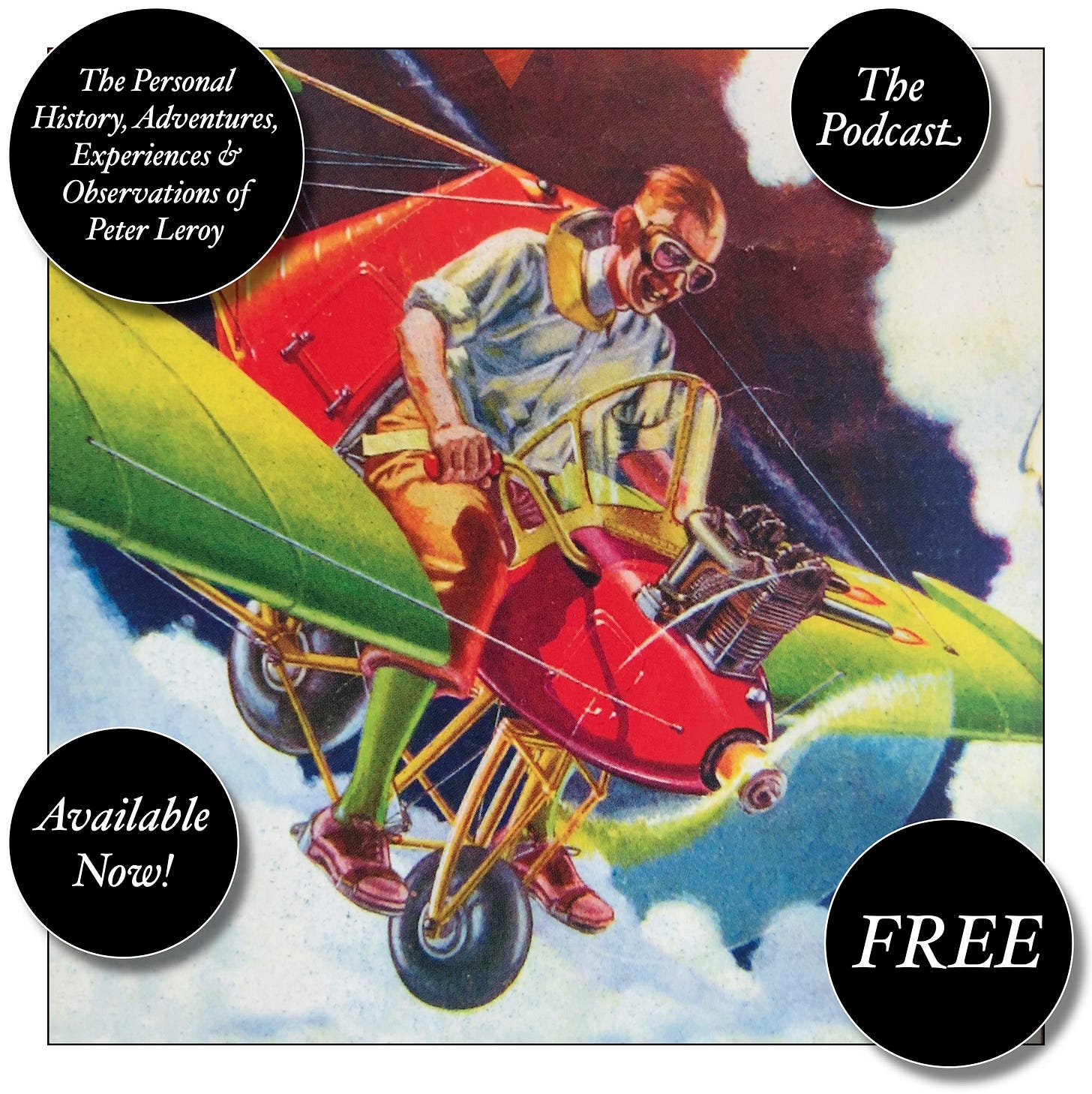

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post