49

“MY FIRST MOMENT ON DISPLAY came the next day. I waited till around noon to go back to the warehouse. When I got there, Denny was hard at work. He worked in an odd, disorganized way, jumping from one thing to another, never finishing one job before he was distracted by the next. It drove me nuts, even that first day. I would follow him, trying to finish what he’d left undone or at least clean up the mess he’d left behind. And throughout it all we were carrying on a discussion—no, not a discussion, two monologues. He was talking about his theater, talking to himself, really. It was a hodgepodge of ideas, a stew, a salmagundi, a chowder. And I was trying to tell him my story. So you had these two things going on at once, these two people, each trying to be heard, and in the midst of it all a voice called out, ‘Hello!’

“We stopped and looked up, and standing in the doorway, silhouetted against the sunlight, there was a skinny man dressed in black. Scared the shit out of me for a minute, but then I realized who it was. Do you remember that guy who used to sell vegetables from house to house?”

“Oh, sure. Drove a black pickup truck, ancient, and his mother, also ancient, rode beside him.”

“And she never said a word.”

“Right. On my block we used to call him the Grim Reaper.”

“Well, there he was, standing in the doorway, and Denny said, ‘Yeah?’

“The guy, the vegetable man, said, ‘Got cabbages, potatoes, radishes, onions, cucumbers, butternut squash. Whyn’t you come out to the truck and look ’em over?’

“ ‘Oh, sure,’ I said, and I put down whatever it was I was doing, and headed out to his truck, all eager and gleeful, because I had always enjoyed it when he would come to the house on a summer morning and my mother and I would pick through the things he had. Denny followed along, but not with the same enthusiasm. He said, muttering into my ear, ‘I wonder how long he was standing there watching us.’

“ ‘Oh, not long, I’m sure,’ I said, but I wasn’t so sure at all.

“Denny said, ‘He seemed to be taking it all in, if you ask me,’ and I poked him with my elbow to tell him to shut up.

“I picked out some vegetables, and Denny paid for them, and the vegetable man gave Denny his change and then said, ‘Puttin’ on a play?’

“Denny said, ‘Well, not yet. Getting ready.’

“ ‘Rehearsin’,’ said the vegetable man.

“ ‘Yeah,’ said Denny. ‘Getting ready, anyway.’

“ ‘When you going to put it on, then?’

“Denny and I looked at each other and we had an instantaneous thought. Very nearly the same thing went through our minds; I know that it did because we talked about it later, as you’ll see in a minute. Here’s what went through my mind: first, I didn’t want to disappoint the old vegetable man, and I wished that I had something to offer him, a play to put on for him; and, second, I had the idea of a play that was like what Denny and I had been doing when the vegetable man walked into the warehouse and stood there watching us. If he thought it was a play, maybe it was. I had the idea of a play that was just life. Not a play that was like life, or a slice of life, but a play that was a life, and a life that was a play.

“So I said, to the vegetable man, but looking at Denny, ‘Tonight.’

“And Denny said, looking at me, ‘Yeah, tonight.’

“The vegetable man said, ‘Well, I’ll bring Mother and we’ll come by, then.’

“He got into the truck and started it up, and turned to us and smiled. I’m sure I had never seen him smile before. I would have remembered it: he had an enormous mouth and long yellow teeth. ‘Something to do,’ he said. He was—gleeful. He drove off and Denny and I stood there looking at each other, wondering what we’d done. In another moment, we were chattering away, and we spent the rest of the afternoon chattering away, because we were so struck by the possibilities of what we had done. A play that was a life. A life that was a play. It had everything we wanted. It had everything we needed. Denny would get to explain his goals for this theater while he was creating it, and his explanation would become a part of it. In a strange way, it would make itself. And I would get to tell my stories and—I suppose you could say—”

She stopped. She took a breath and raised her head, looking upward, toward the rafters or the heavens.

“What?” I asked.

“—confess,” she said.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

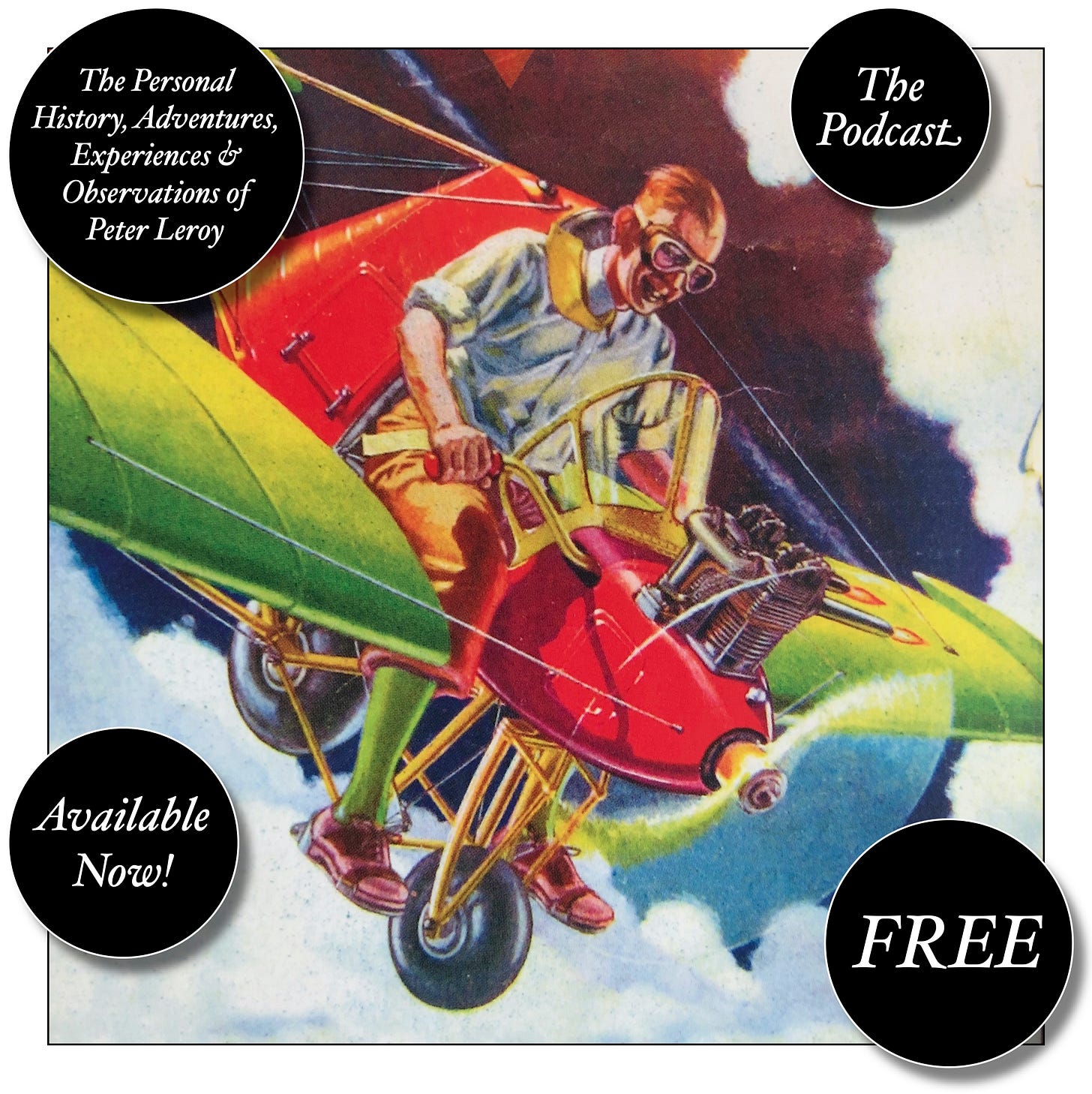

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post