51

“WHAT A DAY that was!” she said. “What a night that was! Everything clicked. But then, how could everything not click? This play was a life, so anything that happened in it was a success, at least in the sense that anything that happened was exactly what we wanted to include in the performance, even if it wasn’t what we would have chosen to have happen in life. Isn’t that a neat trick? Not a bad way to live.”

“Every accident is part of the story.”

“Exactly. And we were blessed with some happy accidents. On that first night, when Denny dashed backstage and lowered the houselights—”

“—for the first and last time,” I pointed out.

“Right! Once the lights went down, they stayed down. From then on, the performance was always in progress. Everyone who showed up after that was a latecomer.”

“To be seated at the discretion of the management.”

“Which maintained a strict seat-yourself policy. So the lights went down, and somewhere up in the rafters a bat that had taken shelter there woke up, looked around, decided that it was twilight and time to get out and find something to eat, spread its wings and fluttered down over the crowd. Well—I say ‘crowd,’ but let’s just make that ‘audience.’ Everybody cringed. I cringed. I grabbed a doily and threw it over my head, because my mother always warned me that bats go for your hair and get themselves snarled in it. The bat got applause, I got applause, and Denny—who shooed it out the door by flapping a poster at it—got applause. When he came back, walking down the aisle toward the stage, I held my hand out toward him, indicating that people should give him a hand, the way I’d seen performers do it on television, and said, ‘How about a hand for our director, and bat boy, Denny—’

“And he said, as if he were correcting me, ‘Gregory.’

“I said, ‘Gregory?’

“And he said, not to me, to the audience, ‘My professional name.’

“ ‘Gregory what?’ I said.

“ ‘Anderson?’ he asked. That was his own name. Apparently his imagination had failed him.

“ ‘Nah,’ I said. ‘It doesn’t go.’

“ ‘I’m open to suggestions,’ he said.

“ ‘I’d give you Lodkochnikov,’ I said, ‘but I’m using it. How about Koochikov?’

“And a voice—a thin, piping voice, like a bird, but strong and clear—called out, ‘Tschudin!’

“So I said, ‘Gesundheit!’ Just like that. It just came out. And it brought down the house. Well—about six people laughed. But that was the house. So it brought down the house.

“ ‘Where did you get that?’ Denny asked.

“ ‘I used to know a man named Gregory Tschudin,’ said the voice. It was the vegetable man’s mother. ‘A very nice man,’ she said. ‘A tailor!’

“Denny said, ‘Well, if you don’t think he would mind, I think I’ll use it.’

“And the vegetable man’s mother said, ‘I don’t see how he could possibly mind, since he’s dead ten or twelve years by now.’

“ ‘So be it, then,’ said Denny. ‘Tschudin the Tailor lives on in me.’ And that was it. That’s how it happened. Right here on this stage. That’s how Denny Anderson, a dreamer, kind of dull, but kind of sweet, became Gregory Tschudin, an innovative dramatist, still a dreamer, and generally a prick.”

A pause for laughter, and then she said, in a serious, almost academic, tone, “That night also brought up the first of a number of questions about what behavior was really part of the contract that I had made to put myself on display—and what was to remain private.”

“You have a contract for this?” I said, with exaggerated surprise and apparent disbelief. “I’d love to see it.”

“Oh, Peter,” she said, with a shake of the head. “You’re quite the little straight man.” Then, with a giggle, she returned to the voice of her Tootsie Koochikov character. “Not a written contract, silly!” she said. She went on in that voice, incongruous as it was: “I’m talking about the tacit agreement that already existed between me and my audience, sweetie.” A pucker as if for a kiss. “I mean, it’s like in the very act of my walking out here and standing in front of them every day, I say to them—tee-ass-itly, you understand, not expressly, per se, as such—‘If you watch me, I will perform for you.’ And when that very first person first came into that drafty warehouse for the first time and took a seat—”

“—the vegetable man—”

“Yes, indeedy. He was saying to me—”

“—tee-ass-itly—”

She put a hand on her hip, knit her brows, and glared at me. “Listen, Peter,” she said. “Let’s not forget who’s the star here.”

“Sorry.”

She went on in the Tootsie voice: “They were saying to me, ‘If you perform for us, we will watch you.’ We had a deal. But the question was, how far did that deal go?” She returned to the serious voice: “And that question, it turned out, would concern us for years.”

“And consume a considerable amount of your critics’ ink.”

“Oh, yes. Yes, indeed. We raised big questions about where the performance ended and life began. For me, now, they are distinct but coextensive, but in the beginning the limits hadn’t been defined. And the question of defining those limits came up the very first night. At the time it looked like one simple question: Were we going to put sex on display, too? Or was that going to be—”

She turned to me for the word.

“—obscene,” I said. You can always count on me to point out the obvious.

“Exactly,” she said. “I think that from the beginning, from that first night, and ever since that night, a certain number of people in any audience have come in the hope that they’ll get to see me doing it with somebody or other.”

She paused and did a long, slow turn in my direction. She wore a lecherous smirk.

A low, snickering laughter spread through the audience. I’m sure I blushed.

She turned back to the audience and said, smirking at them this time, “And you know who you are.”

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

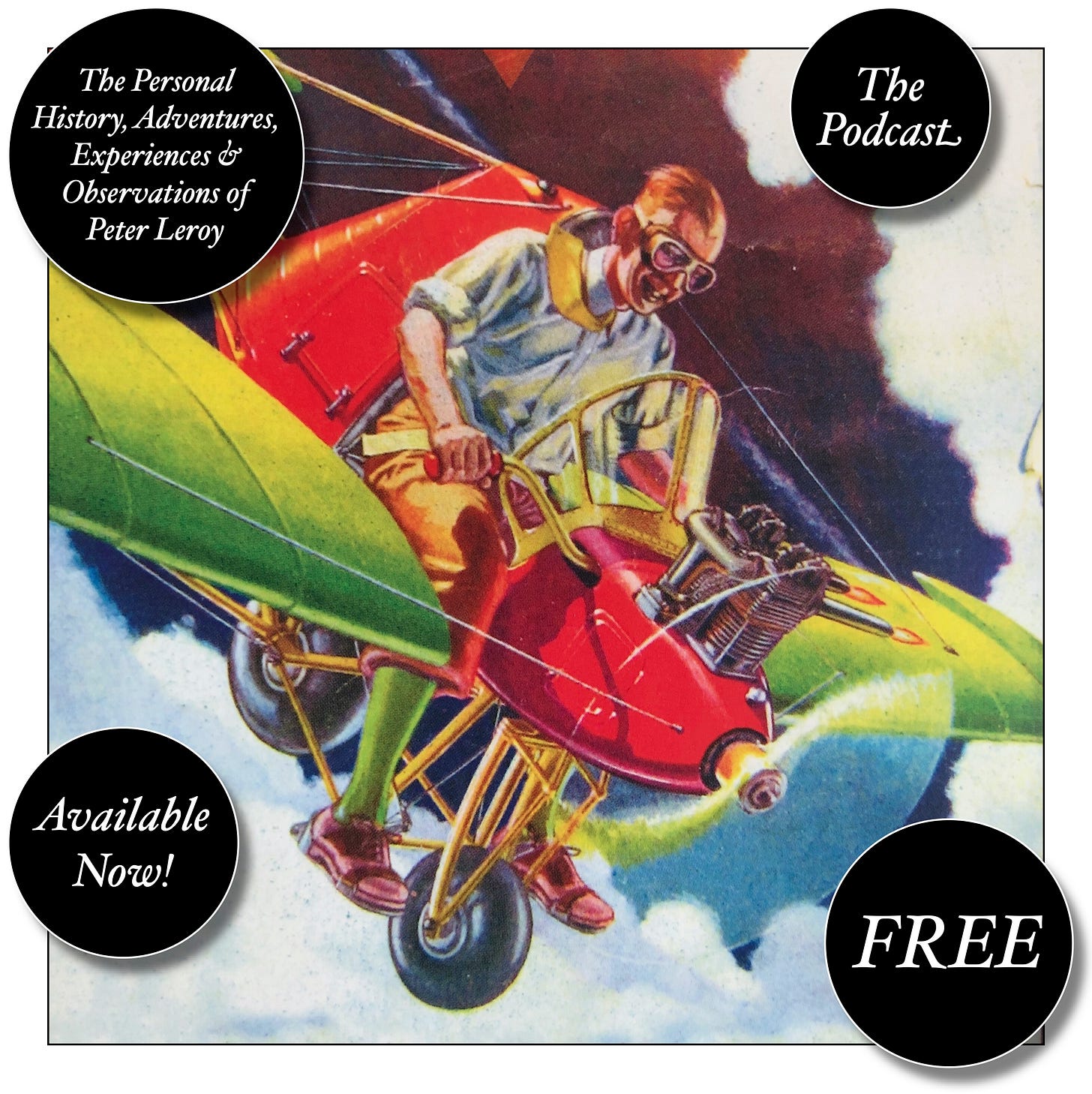

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.