DUNCAN ROLLO, chairman of the Babbington Zoning Board, opened the door at the back of the auditorium, allowed himself only a moment to glance around and size up the situation, then marched right down the main aisle to the edge of Ariane’s living room, where there would have been a wall if she had had any walls.

“Ariane Lodkochnikov?” he said.

“Who’s there?” said Ariane, as if she couldn’t see him standing there but heard a small voice through a thickness of insulation, straining to hear, swiveling her head.

“Zoning,” said Mr. Rollo, raising his voice in response to her apparent deafness.

“Would you mind coming around to the back door?” she shouted.

“Huh?” he said, looking this way and that. “What back door?”

“Around by the kitchen,” she said.

Since it was the middle of the afternoon, there wasn’t much of a crowd, just a group of housewives who had taken to coming to watch Ariane now and then. They were members of a club, a coffee klatsch actually. Originally, they had met every Thursday at the home of one of their members (on a rotating basis) for coffee and conversation, but after Ariane went on display they began meeting at her house instead, in the café at the back. When they first began coming, the café wasn’t in operation, so each of them brought a thermos of coffee and (on a rotating basis) one of them brought baked goods. The coffee-klatschers laughed at Mr. Rollo’s confusion, and Mr. Rollo, a small, puffy man who wore his shirt collars too tight and prided himself on having no sense of humor, reddened.

Mr. Rollo walked around the edge of the stage until he came to the stairs that led up to the back door, which stood within a frame, but stood alone, with no walls beside it. The door had a window which was covered on the inside by a sheer curtain. Mr. Rollo rapped on the window. Nothing seemed to happen for a moment, though he heard a buzzing and tittering from the women who were drinking coffee at the back of the hall. They were reacting to Ariane’s pulling the kerchief out of her hair, shaking her hair out, checking herself in the hall mirror, and touching up her lipstick, just as they did when the doorbell rang at their own homes.

Ariane went to the kitchen door and pulled the curtain aside. She regarded Mr. Rollo quizzically. “Yes?” she said.

“Zoning!” said Mr. Rollo, louder than was necessary.

“What can I do for you, Mr. Zoning?” said Ariane.

“Mr. Rollo,” said Mr. Rollo. “I’m from Zoning. The Zoning Board.” Ordinarily, he enjoyed the moment when he announced himself to a citizen more than any other aspect of his job. He was accustomed to seeing a sudden flash of fear when the word zoning buzzed through the air. The Zoning Board was a powerful entity in Babbington, and it was growing more and more powerful as the available land ran out and questions about the character of the town, the face that it ought to display to its audience, the outside world, consumed more and more of the time and energy of Babbingtonians of all stripes and strata.

“How interesting!” said Ariane. “You’re one of those people who identifies himself by his occupation.” She opened the door and let him in.

“What?” asked Mr. Rollo, his rhythm wrecked.

“Well,” said Ariane, “when I first asked, ‘Who’s there?’ you said, ‘Zoning.’ You didn’t say, ‘Mr. Rollo.’ I mean, if you’d been the trash man and I’d asked you, ‘Who’s there?’ would you have said, ‘Trash’?”

There was quite a bit of laughter at this.

“Very funny,” said Mr. Rollo.

“More interesting than funny,” said Ariane. “I mean, take the case of Death. Now there’s somebody who is what he does—”

“I’m here on serious business,” Mr. Rollo declared, in a tone that hinted at the serious consequences that might befall a young woman like her if she persisted in not taking him seriously.

“Well,” she said, “you couldn’t get much more serious than Death—”

“This is a zoning matter,” said Mr. Rollo, with the suggestion that zoning might very well be more serious than death.

“I see,” said Ariane.

She turned toward the audience and rolled her eyes.

“Are you aware,” said Mr. Rollo, inflating himself like a puffer under attack, “that you are dwelling illegally in a building that is not zoned for habitation?”

“Dwelling?”

“Living.”

“You call this living?” she asked, indicating her modest circumstances with a sweep of her hand.

“Yes, I do. I see a kitchen. I see a bed. I presume that there is a toilet in that cubicle over there. And I know from reports I have received that you are in residence here twenty-four hours a day. I call that living.”

“Well, then, I’ve fooled you, haven’t I?”

“In what way have you fooled me?”

“Well, look out there. What do you see?”

“See? I see seats. A few people. Tables in the back—”

“You see a theater.”

“More or less.”

“And what does a person go to a theater for?”

“See a show—”

“And those people out there came to see what?”

“You, I guess.”

“There you are! This isn’t living. This is a show. It’s like living. It looks like living. But it isn’t. It’s a show. It’s not real.”

“You have a real kitchen and a real bed and a real toilet—”

“Props.”

“But they work.”

“That makes them more convincing. More realistic.”

Mr. Rollo rubbed his chin. “Do you cook meals in that kitchen?” he asked.

“Oh, sure,” she said, “when I’m playing the part of a woman cooking a meal in her kitchen.”

“What woman?”

“What do you mean?”

“You said you play the part of a woman. What woman?”

“Ariane Lodkochnikov.”

“But you are Ariane Lodkochnikov.”

“I am Ariane Lodkochnikov, but not the Ariane Lodkochnikov I play here on the stage. You see—”

The conversation continued along those lines and extended well into the night. Ariane made some dinner (pork chops, brussels sprouts, and mashed potatoes), and Mr. Rollo allowed her to put a plate in front of him. He took fork in hand, and a hush fell over the audience. He looked around. He realized that he was slouching and sat up a little straighter. He ran his fingers through his thinning hair. The fork grew heavy and large, so unwieldy that he had to concentrate on manipulating it. He tried to hide the difficulty he was having, but not until he felt that he had the fork under control did he dare to grasp the knife in his other hand and cut a bite of pork. He performed the chop-cutting with what he hoped was both a display of his forceful technique with a table knife and his reckless disregard for the impression he made on anyone who might be watching him. He put the bite in his mouth and chewed it more than he ordinarily would have, now and then raising an eyebrow or murmuring contentedly to indicate that he found it good. He patted his mouth with the napkin and leaned across the table to whisper to Ariane: “Do you go through this every time you eat dinner?”

“Yes,” she said. “You get accustomed to it, but you never stop being aware of it. You are always saying to yourself, ‘Now they are watching me pick up the knife, and now they are watching me cut the meat, and now they are watching me chew it.’ ”

“It must be exhausting,” he said. He looked at the chop. It was good. He would have liked another bite.

Ariane opened a couple of bottles of beer. “Here,” she said. “Have a beer. It helps.”

Mr. Rollo drank the beer, and in the end he ate three pork chops and two helpings of mashed potatoes. He didn’t finish his brussels sprouts, and he was quite sure that everyone noticed that he didn’t finish his brussels sprouts, but he felt that not finishing the brussels sprouts showed that he was an adult man, independent not merely of his mother but even of the memory of her insistence that he eat his vegetables. In his heart of hearts, he knew that he would not have dared to leave brussels sprouts on his plate at home, where his wife was capable of bringing to the question “Something wrong with those?” the full weight and authority of his mother’s sainted memory, and so he decided that Ariane must be right, that he was not actually living during the time he spent in her company here but was playing the part of someone who was not quite himself. He shoved the plate aside. He liked the feeling.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

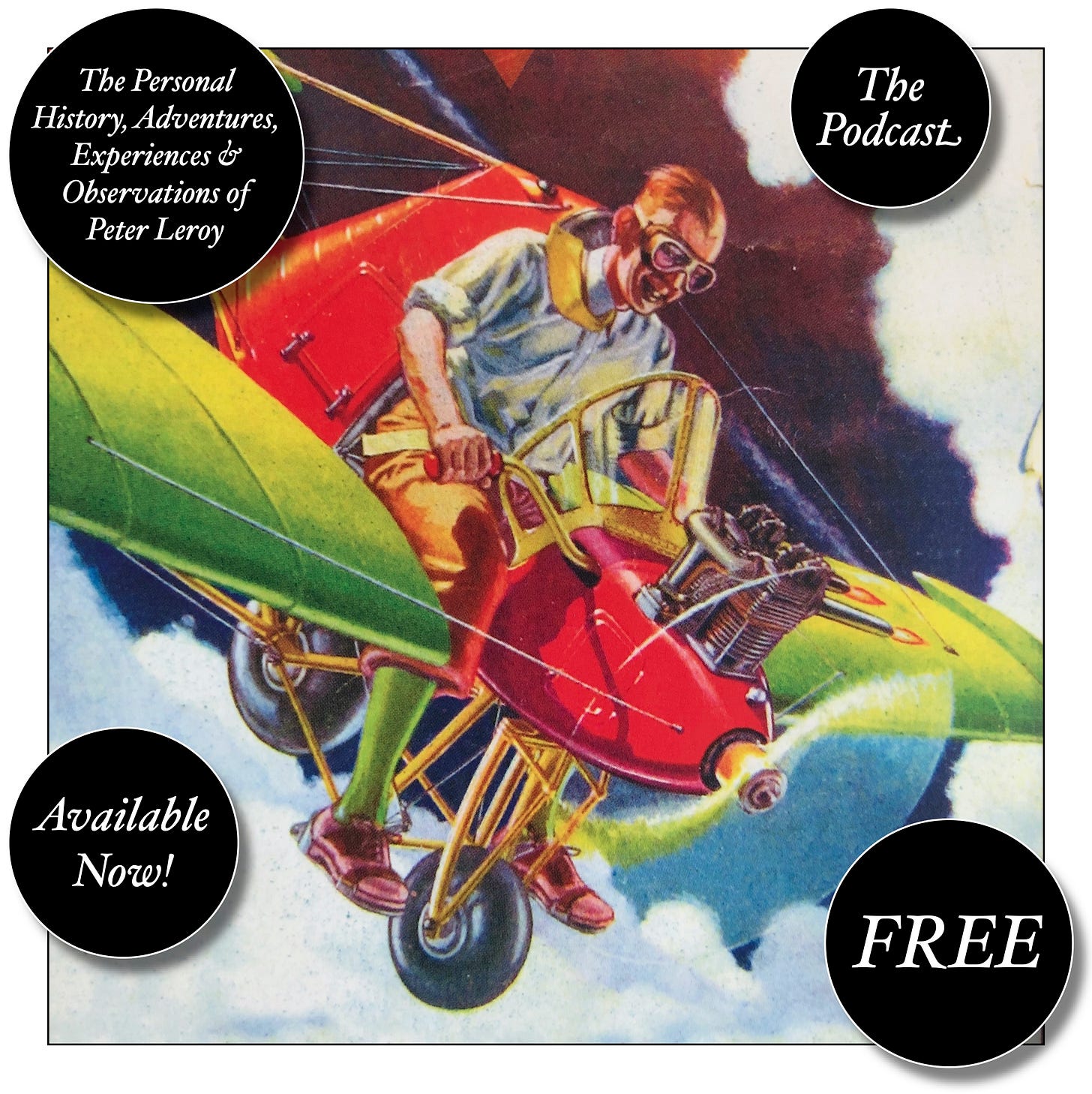

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.