63

FROM The Films of Gregory Tschudin, by Andrew Cargill:

On Display

Daniel Turner (Hal Sorento), a builder who has been invited to bid on the construction of a house, is in the office of Terry Carp, a young architect (Jerry Burke), puzzling over a set of house plans. With an endearing affection for his own work, Carp explains the details of his drawings, and Turner knits his brows and grumbles and scratches his head as if he hasn’t got a clue about what the heck these strange lines might represent. The house (an intriguing place that owes a lot to Frank Lloyd Wright), is to be the retreat of a beautiful and famously reclusive actress. It will be built atop a bluff beside the pounding sea (Tschudin’s favorite location).

The young architect refuses to reveal the identity of the client, but his breathless hints whip Turner into a frenzy of eager anticipation (and we can tell that he’s in a frenzy of eager anticipation because he knits his brows, scratches his head, and grumbles all at once). When Turner is finally chosen as the contractor, the architect announces, with boyish excitement, that the house will be built for . . . Theresa Foran. Turner’s look in response to this news is so stony and blank that he seems lost in another picture. Apparently, Theresa Foran isn’t anyone he’s heard of. “The actress,” whispers the architect, but Turner just shrugs.

However, we follow Turner home that night, and his den or television room looks like a shrine to Theresa Foran. He has posters of her films on the wall, glossies, and a library of videocassettes. When Miss Foran (Danielle Court) comes to the site Turner seems blind to the fact that she’s beautiful, sexy, and rich, but every night, after his day on the site is done and he’s at home by himself, he watches videos of her movies. While he watches, entranced, we watch, too, over his shoulder. This theme of the watcher watched is Tschudin’s finest conceit; it not only drives the action of the film but connects us with it, since we are the next level of watchers watching, watching Turner watching Foran. We are forced into tacit acknowledgment of the voyeurism that makes us moviegoers, to confront our complicity in whatever may ensue. Whatever may befall these characters, we are accessories to it; nous avons les mains sales. Tschudin never fills the theater screen with a scene from one of Foran’s movies. Instead, we always see a television screen partly obscured by Turner: we are always watching him watching her, never simply watching her.

Soon it is clear that Turner’s interest has become an obsession—as clear as the much-discussed masturbation scene can make it. Looking at this now, when time has passed and the dust of the debate has settled, it seems fair to say that Tschudin handled it about as well as it could have been handled, which is to say that we never actually see Turner handling anything; we simply watch him watching one steamy scene after another from Ms. Foran’s oeuvre, but we are, as usual, looking over his shoulder while he watches, and his shoulders move with what might be described as an unmistakable rhythm.

Turner begins a campaign to turn Foran against Carp. At first, he seems to have no reason for this beyond his obsession with Foran; we assume that he wants her to himself. Eventually he persuades her to dismiss Carp and put him in sole charge of completing the building. (From this point on, the film could be read as a cautionary tale about the dangers of building without the services of an architect.) With no one who isn’t on his payroll to question what he’s doing, Turner alters the plans to suit his needs as an obsessed voyeur, producing something like the panoptic arrangement that Jeremy Bentham (the eighteenth-century utilitarian philosopher and social engineer) proposed for prisons. He constructs a hollow core at the center of Foran’s house, running most of its length, accessible from a matching central core in the basement, which can be reached through a tunnel, supposedly built as a drainage tunnel, that runs to the cliff at the edge of the sea.

When the house is finished, Turner beg ins spending all his free time in the observation core. He has provided himself with chinks and gaps in the intricate wood paneling, so that he can follow Foran’s movements from room to room and observe her virtually everywhere—from bed to bath. What he sees, in addition to a very full sex life, is Foran being swindled outrageously by her manager, Geoff Hansen (Nelson Birch). Because we see Turner seeing it all, we begin to expect him to expose Hansen and thereby win Foran’s heart and all the other delectable parts that go along with it.

That, however, is not what Turner is interested in. He only wants to watch, not to participate. As far as he is concerned, her life is played out in another realm, no more accessible to him than the intangible world of light and shadow where her characters live for the length of a videocassette. He is a part of her audience, not a part of her life.

Enter the young and relatively innocent Terry McDermott (Doug Walensky), the son of an old school chum of Foran’s, who arrives with wide eyes and a lame excuse about needing a summer job. Foran welcomes him into her household as amanuensis and hanger-on. Young McDermott soon recognizes the bloodsuckers for what they are. Late one night, when Foran, Hansen, and McDermott are gathered in Foran’s living room for that one too many (while Turner watches from inside the walls, of course) McDermott challenges Hansen with what he’s discovered. From this point, things happen very quickly. Hansen flies into a screaming rage and begins beating McDermott mercilessly. He drives McDermott up against the wall of the observation core, and there he continues punching the poor kid senseless. Foran grabs a gun from the drawer of an end table, and aims it at him, screaming at him to stop. Turner, inside the wall, hears her screams but his view is blocked by Hansen and McDermott, so he can’t see that she has a gun. McDermott sags to the floor, and Hansen spins around to face Foran. He is wearing such a maniacal, hell-bent look that she fires again and again and again, hitting Hansen and Turner, who is right behind him, inside his observation core. They collapse in lifeless heaps, though Foran sees only Hansen fall, of course. She stands there, the gun hanging heavy in her hand, dumbfounded by what she’s done—but not knowing the half of it.

End of picture. At the time of its release, Tschudin said that of all his films only On Display ended exactly as he had intended.

[to be continued]

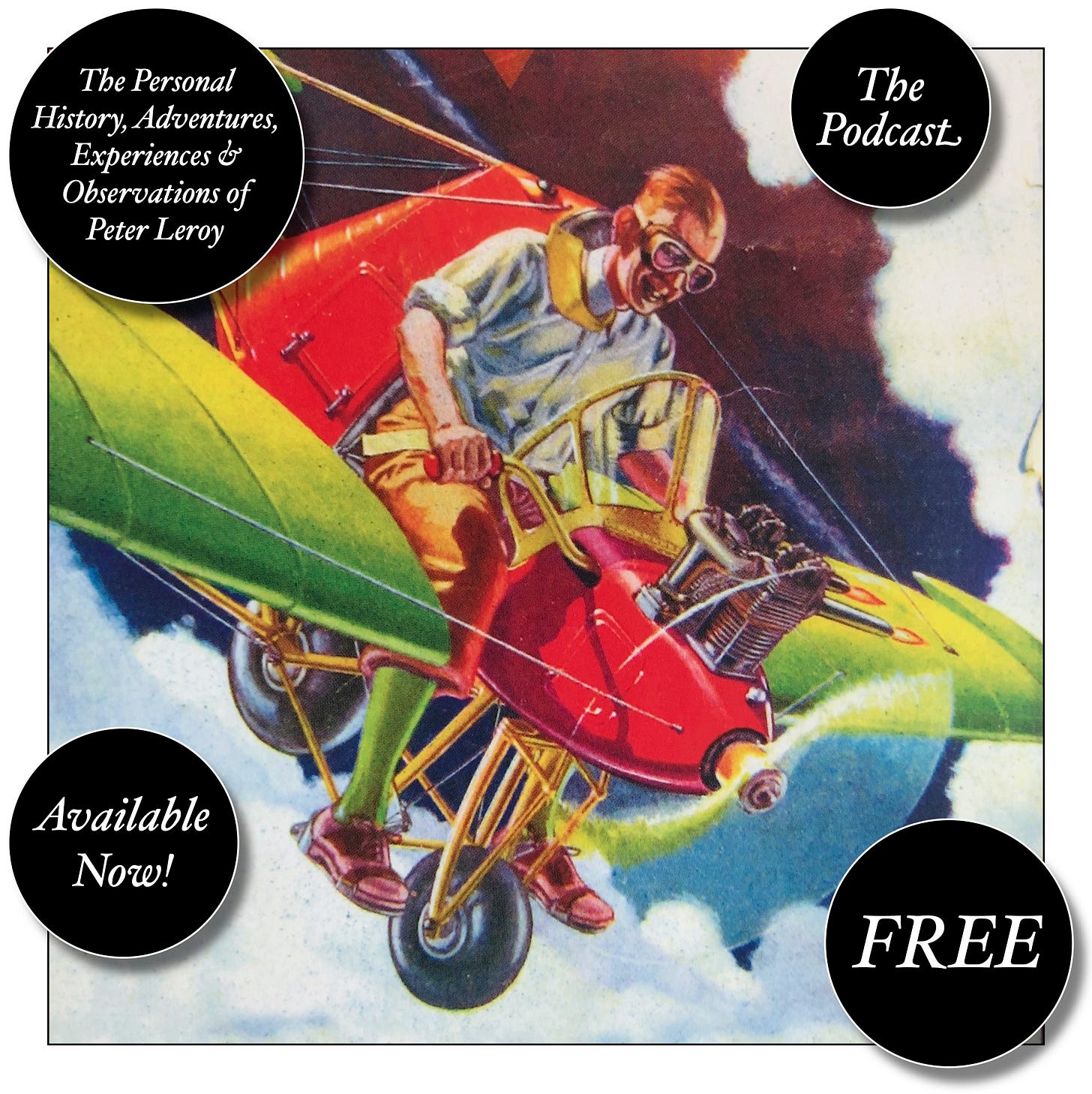

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post