Preface

I WASN’T IN THE CROWD that gathered to watch the Nevsky Mansion burn, because I hadn’t been born yet, but if, on a September night, when the weather cools suddenly and the haze of summer drops as dew onto autumn’s lawns, leaving the night air clearer than it has been for months, so that the moon illuminates my insomniac hours like a searchlight, with a brilliance quite unlike the phosphorescent softness of summer moonlight, I happen to see sweet autumn clematis growing on a wall, I am reminded of all the stories I’ve heard about the night the mansion burned, and I’m also reminded of other nights, certain wonderful autumn nights when I was a boy, nights when I scaled the walls of the Glynns’ stone house and slipped into bed with Margot and Martha, those scented nights I spent abed with twins.

Thanks to the god of happy accidents, it seems that every September there is a moonlit night when I do happen to see sweet autumn clematis growing on a wall, and so every year the memories return to me—the stone house, the welcoming Glynns, the clematis, the wall, the rope ladder, the narrow window, the plump comforter, the tutorial twins.

I recall those nights now with a certain sadness. In part, it’s the sadness that I find implicit in any memory, a yearning for my younger self and the fresh flavors of his new sensations, and in part it’s a kind of mourning for the distinctions that die with the passage of time, for in my memory now those silvery nights have begun to run together, to touch at the edges and adhere to one another like pancakes too close on the griddle. A novelty has a brief life, and only one, with no possibility of resurrection, so I would have been wise to take notes to preserve each night as a distinct memory, and I would have taken notes if I had realized that I would never, after those nights had ended, quite manage to bring each of them back as the singular experience it was. I suppose I never will, but in At Home with the Glynns I’ve done the best I can.

So, there’s a certain sadness in my reminiscences of the Glynns, but sadness doesn’t dominate them. Pleasure does. It’s sexual pleasure, of course, but sexual pleasure amplified and augmented by the thrill of adventure, because for me the pleasure of recalling the Glynns begins with the recollection of my daring route into Margot and Martha’s bedroom.

I remember the way I would dart to a dark corner of the Glynns’ garden, where the overhanging trees blocked the moonlight, like a freedom fighter or a cat burglar in a shadowy movie. I would scale the garden wall and crouch atop it, where I could look down into the garden courtyard and into the kitchen at the back of the house, then clamber along the wall until it ended just below Margot and Martha’s window. There, in the dangerous moonlight, I would—

Wait a minute. The moon can’t always have been shining. It waxes and wanes, after all, and in Babbington in the fall many nights are foggy, nights of mystery and mishap, when things don’t seem to be what we suppose them to be, and nothing seems to happen as we expect it will. There must have been some nights like that, nights of wrong turns, chance encounters, and hidden dangers, when I bumped into the Glynns’ suspicious dog on my way to climb the wall, alarmed the household by blundering into their trash cans, or tossed pebbles against the wrong window, but I don’t recall them. (My art is made of recollection, and revision, and wishful thinking.)

So: in the dangerous moonlight, I would have to wait—warily, pressed against the wall—until the girls dropped the ladder they had made. I would remind myself that I couldn’t toss pebbles at their window or call to them, or whistle, because the window beside theirs was their parents’. I had to wait.

Patience was one of the things they taught me.

When at last the window swung open and they let the ladder down, I climbed up and out of the chilly night and tumbled into a fairy land, a shadowy landscape of rumpled sheets and pubescent skin.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

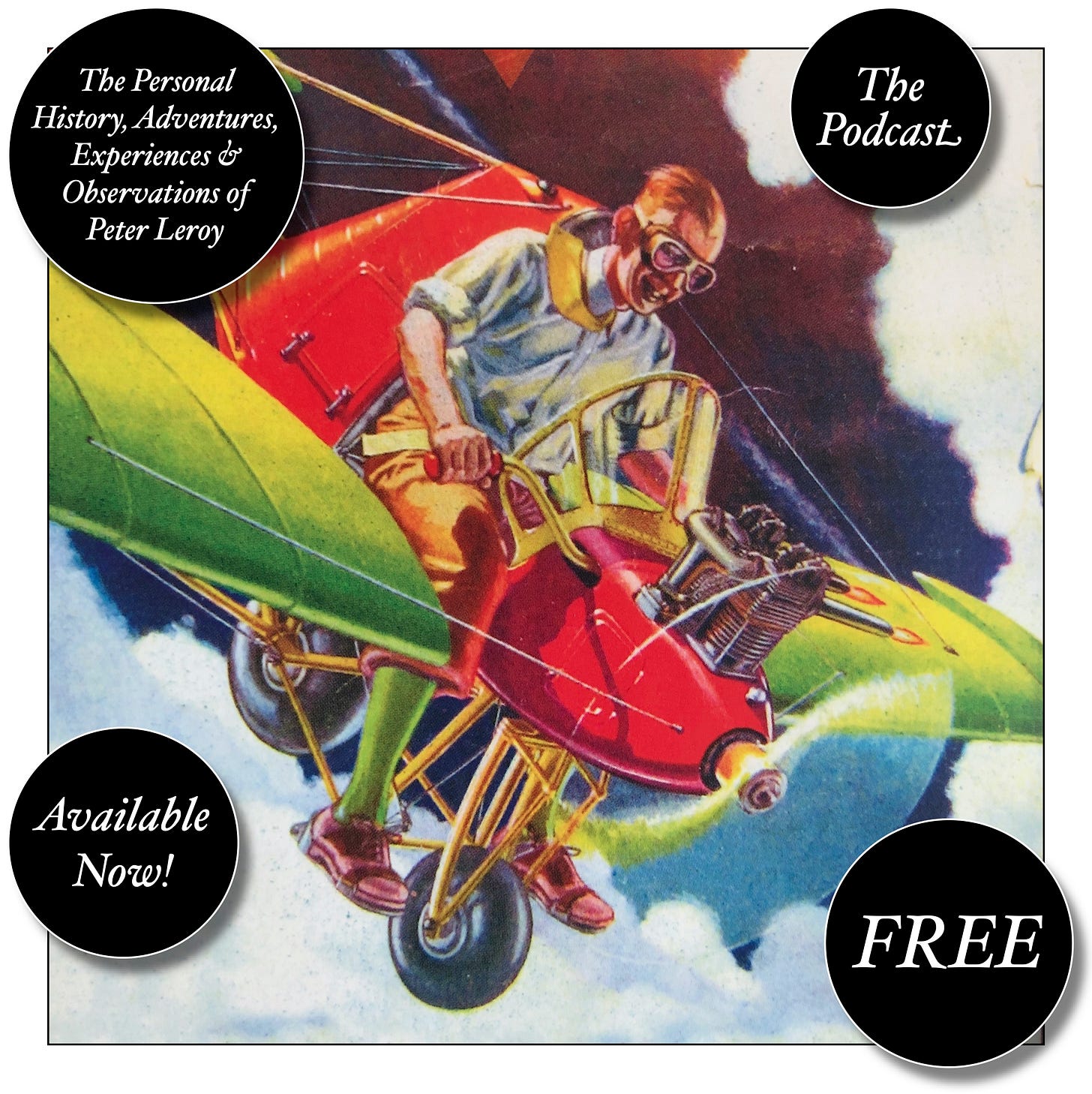

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.