THE GLYNNS LIVED in what had been the carriage house for what had been the grandest house in Babbington. It was really the only house in Babbington that might reasonably be called grand at all. In a sense that I’ll attempt to explain shortly, it still was the grandest house in Babbington, although it had burned down years ago. The big house itself was always referred to, during my childhood, as “the Nevsky mansion,” though it was just an abandoned shell, hollow and mysterious, a dangerous place to go according to Babbington’s mothers, but a powerfully alluring place for Babbington’s children, the sort of place that in legal parlance is “an attractive nuisance,” which appellation must surely have arisen from a knowing recollection of childhood.

The night the Nevsky mansion burned (a night about sixteen years before the events I’m relating here) was a Babbington milestone, a memorable moment, a momentous event, especially for people in my parents’ generation: for them it became a standard that they used to gauge the significance of others.

I heard about the fire often. Everyone who had seen it (and, I suspect, some who hadn’t) had a story to tell about it. The conventional beginning to these stories was the storyteller’s lament for a lost time, a time that had ended the night the Nevsky mansion burned. Following the lament came the recollection of where the storyteller had been and what the storyteller had been doing at the moment when the fire sirens sounded or the mansion’s red glare lit the night sky.

Young Babbingtonians were frequent targets for these stories. If you had been a young Babbingtonian when I was, you would have found it nearly impossible to go more than a couple of days without hearing a version of “The Night the Nevsky Mansion Burned.”

You might be stopped at a gas station, pumping air into a bicycle tire, for example, and feel an avuncular hand on your shoulder.

“That’s right,” a voice would say. “That’s the way to do it. Have your fun while you can.”

“Huh?” you might say.

In reply you’d hear a wistful sigh, and you’d know then, for certain, that you were in for it.

“You won’t be young forever, you know,” the voice would say. “Soon enough the time will come to put away childish things. Soon enough it will all go up in smoke. For me, it all went up in smoke one night when I was just a little older than you are. Seems such a long time ago, now. It was—well, it’s a long story.”

Here you would have to make a decision. If you wanted to get out of hearing the story, you could plead a pressing errand for your mother, but if you were willing to hear the tale out, you could bargain for a fee.

“Gee, that sounds pretty interesting,” you might say. “I’d like to hear more about it, but I’m kind of hungry, and very, very thirsty, so I guess I ought to be getting home, where I can get a Coke and a snack.”

“Well, now! You can get a Coke right here! They got a machine right over there. Let me get you a Coke and one of those little bags of peanuts and I’ll tell you the whole story.”

“I’m crazy about licorice.”

“Well, licorice then.”

“And peanuts.”

“Oh, sure. Sure. You see, it was an ordinary night—that is, it seemed like just an ordinary night, at first. I guess I’ll never forget what I was doing when I heard the sirens start to wail—”

I really was crazy about licorice, and I was a good listener, so I have enough secondhand experience with the night the Nevsky mansion burned to imagine my parents and their coevals standing around the fire, having been drawn to it from all over Babbington by the fire sirens or the red glare in the sky, already beginning to tell one another the stories that they would go on telling for years to come.

Standing, facing the fire, they would have felt the heat of the flames, and yet they would also have felt, since it was late in the year, a chill on their backs, and so, oddly, the flames might have seemed comforting, the night air unsettling, just the opposite of what one might ordinarily have expected. I can’t say for sure, of course, since I wasn’t there, but I’ve thought about it, and I have stood in front of the Nevsky mansion in approximately the spot where my parents might have stood, on a night late in the year, and so I can say with some confidence that it might very well have been so, because when the wind picked up and I felt the chill, I would have found a fire a comfort.

The whole experience must have drawn them closer, all of it—the fear, the warmth, the chill, the fact that they were gathered in the same place at the same time, drawn together by a single summons. I can imagine, for example, my mother, just sixteen at the time, standing with her two boyfriends: my father and his brother, Buster.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

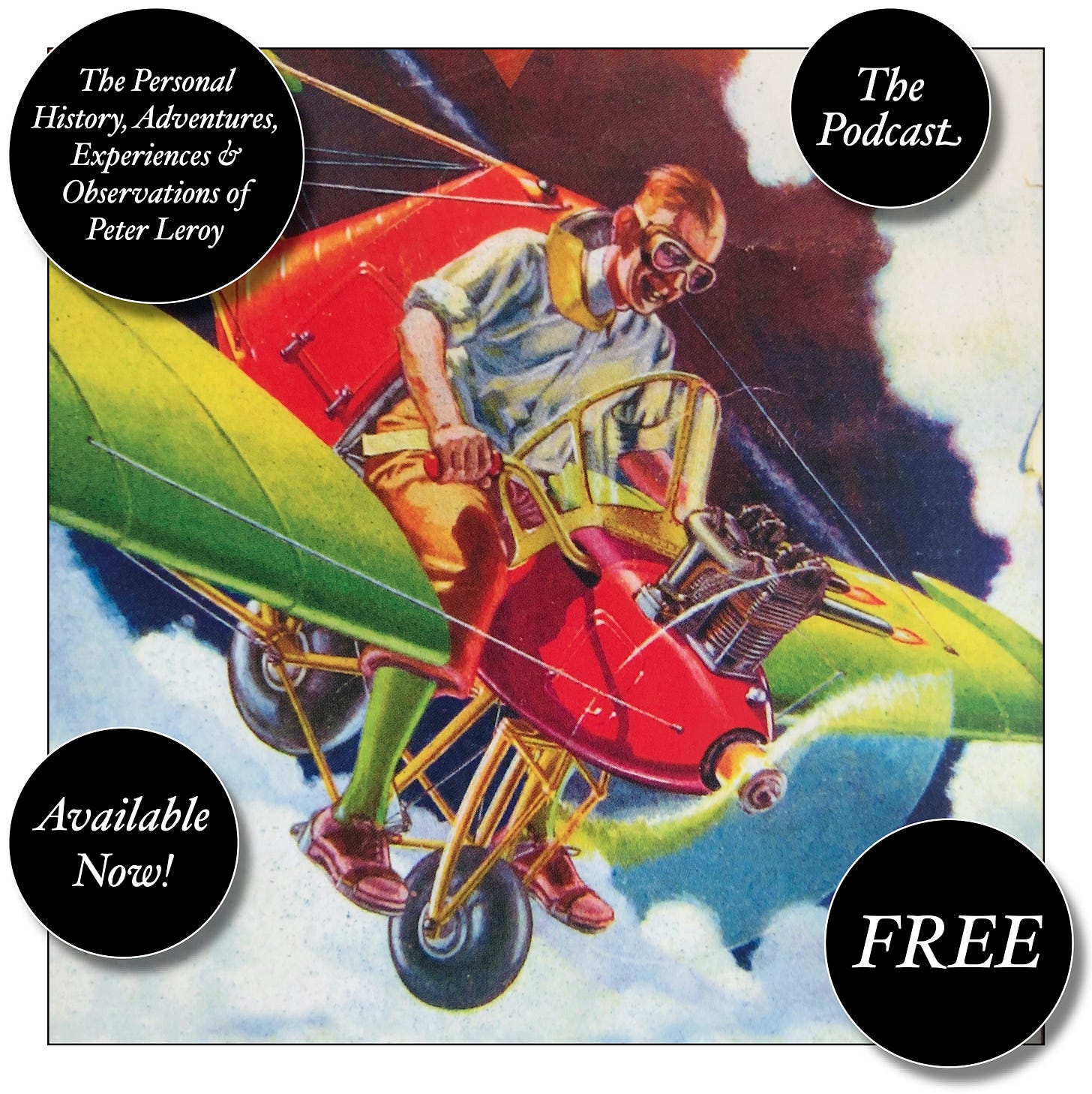

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post