Margot pointed to a ladder, a jerry-built and flimsy thing, standing away from the comforting solidity of the stone walls, leaning against nothing more than one of the narrow catwalks above. I knew what I had to do: mount the ladder, climb up, make my way across the rickety boards to Mr. Glynn’s side, and make conversation with him. I had to try to win him over. I had to do this for Margot and Martha, my friends. I started up the ladder. Climbing it, with the ladder flexing and swaying every time I moved up a rung, I was able at last to put my finger on the uneasiness I had felt from the moment I had entered the Glynns’: I felt like Jack, in “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Now I was climbing the beanstalk. In a moment I was going to have to confront the giant and try to put something over on him, trick him, pull the wool over his eyes. Why am I thinking that? I wondered. I don’t have anything to hide. There’s nothing up my sleeve. Why do I feel so dishonest?

I reached the catwalk, stood there a moment congratulating myself, and looked down at the girls. Martha put her hands together and shook them beside her head to congratulate me, but Margot was making a waving motion and pointing to her wrist, as if there were a watch there, urging me on. I made my way, with a tightrope walker’s mincing steps, to Mr. Glynn’s side.

He had put the rag aside and was working at the canvas with a roller. I knew no other artists, so I didn’t know how to talk to him, what style to use, what approach to take, but the sight of the roller encouraged me some, since I had a little experience painting with a roller. I had helped my parents paint my room. Most of my work had been confined to cleaning up, it’s true, but still I thought I saw a useful opening, or, more accurately, a small overlap in our lives and our selves (the kind of overlap that my friend Mark Dorset, the psycho-sociologist, has illustrated so tellingly in the modifications of Venn diagrams that he calls Dorset diagrams), and so I felt that I could talk to Mr. Glynn.

“I see you use a roller,” I said—ingratiatingly, I hoped.

“Among other implements,” he said, and he cleared his throat, or, perhaps, growled.

“Uh-huh,” I said, and then added, with a modest shrug: “I’ve used a roller myself. Now and then.” As soon as I said it, the thought occurred to me that Mr. Glynn might have begun his career by helping his parents paint his bedroom.

“Umph,” he said. He made a face as if he’d smelled something odd and unpleasant. The giant, I recalled, was exceptionally good at smelling a rat.

“You can cover a large area pretty fast with a roller,” I said, quoting the clerk at the paint store who had talked my father out of painting with brushes. I was by now quite taken with the notion that maybe I had taken the first step on my way to becoming an artist myself that bedroom-painting afternoon, while I was grumbling my way through the cleaning of the rollers. It was an exciting thought, all the more exciting for having come to me entirely unexpectedly.

“Umph,” he said again. I wasn’t making much progress. I tried to bring to mind some more of my roller experiences, but they didn’t go much further than cleaning the damned things. “They’re hard to clean,” I said after an awkward interval.

He turned and looked at me. I was grinning with the pleasure of the notion that I was well on my way to becoming a painter myself, a picture painter, not a bedroom painter.

“I don’t bother anymore,” he said with a wink.

“You mean you just throw them out?” I asked.

“Yeah.”

“Wow,” I said.

This was my first introduction to the devil-may-care attitude of artists. I was powerfully attracted to it immediately.

“Here,” he said, holding the roller out toward me. “Draw your favorite animal.”

I knew what this was. It was a test. I knew from fairy tales that small boys like me in situations like this were always being required to pass tests in order to win the companionship of maidens or escape the wrath of enormous men in leathern garb like aprons or buskins. I felt confident for a moment, simply because I understood in the broadest terms what situation I was in, but then, holding the roller, looking at the canvas, I realized that none of the details were familiar. The notion of using a roller to make a picture of something had never occurred to me. Suddenly a roller seemed the wrong tool for the job. Everything I’d learned during the painting of my room was going to be useless in this test. I stalled while I tried the heft of the roller, thinking about what I might draw.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

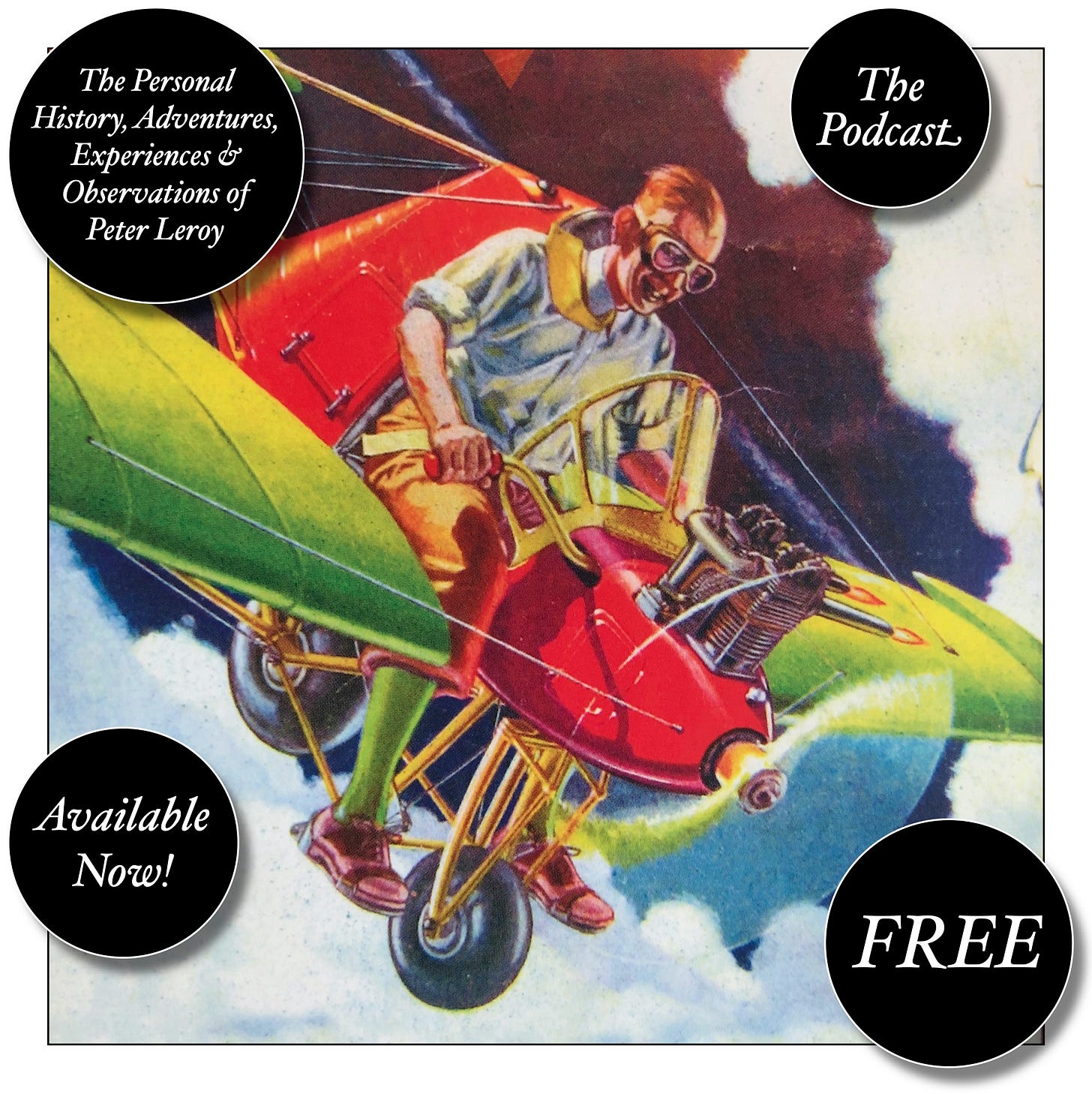

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post