“You misunderstand me, sir,” said the man, the ice in his voice melting. He was a small man with a round face, cherubic cheeks, and a bashful manner. “I’m here to help you.”

“To help us?” asked Rosetta. Her suspicion was plain.

“From your tone of voice, I sense that you are suspicious, madam,” said the little man.

“It was your tone of voice—” Rosetta complained.

“Mine?” asked the little man.

“Yes,” said Andy, “there was something bitter in it, something threatening.”

“Something accusatory,” said Rosetta.

“No, no,” said the little man. “I grant you there may have been an edge of bitterness, perhaps, or acidulous cynicism, the gruffness of a veteran of life’s knocks and setbacks, but nothing threatening, certainly nothing accusatory.”

“You’re sure?” Andy asked warily.

“Oh, yes. Be assured that I am here to help you.” To Andy, he said, “In fact, I am a great admirer of your work.”

“Oh?” said Andy.

“Yes, yes. You are part of a grand tradition, you know. Well, perhaps grand is not the word. You are a fool—”

Andy tightened his grip.

“—that is, a clown—”

Andy twisted the man’s coat until he was choking.

“High praise! High praise!” the man squeaked. “You have made a mockery of them. You have made them appear ridiculous. They are ridiculous, of course, but they don’t always appear ridiculous to those who can’t see beyond the handsome uniforms they give themselves, their tidy grooming, their goose-step, their polished boots, but in your depiction of them, you leave no doubt about it—we see that they are ridiculous.”

Rosetta squeezed Andy’s hand, and Andy relaxed his grip on the little man.

“You are the front line of resistance,” said the man. “You are the father of revolt. Surely you have heard the expression ‘Repression is the mother of metaphor’?”

“I’ve heard that,” said Rosetta.

“Thank you,” said the little man, with a courtly nod toward Rosetta. “Well, if repression is the mother of metaphor, contempt is the father of revolt.” To Andy, he said, “Before those wall paintings appeared, we felt fear, and fear is the mother of—” He hesitated. He put his hand to his brow.

“Capitulation?” suggested Rosetta.

“Submission?” offered Andy.

“Maybe. Maybe. I was going to say—oh, what was I going to say? I know—acquiescence. But perhaps you’re right.”

“No, no,” said Rosetta, sympathetic now. “Acquiescence, that seems right.”

“If you insist,” said the man, with a shrug. “Well, then, on the one hand, fear is the mother of acquiescence, but, on the other hand, contempt begets ridicule, and ridicule begets resistance, and resistance begets defiance, and defiance begets revolt. So you see,” he said, venturing to look Andy in the eye, “you are the father of revolt.”

“The great-grandfather,” said Rosetta.

“What?”

“Defiance is the father, resistance is the grandfather, and ridicule the great-grandfather, according to your scheme of things, and ridicule is where the Bat comes in, so the Bat is the great-grandfather of revolt.”

“Hush!” said the little man, looking around in alarm. “Don’t say that again, ever.”

“What?”

“That name. The name of the little creature of the night. That little creature is dead, my friend. That’s the way it must be. Listen to me.” He glanced around warily, then continued. “You’ve come through a lot, as you said. I know. Everyone who makes it across that border has come through a lot—but you have still a lot to get through, I’m afraid. You have other borders to cross. And you have to begin a new life elsewhere. To do that you have to find a way to live elsewhere, to support yourselves. And you have to find a way to hide,” he said, glancing warily around him again, “from them.”

“Surely not when we’re—far away,” said Andy.

“Oh, yes, yes, even then. For you have offended them, and I fear that they will come looking for you.”

Andy and Rosetta drew together, and Andy put a protective arm across her shoulders.

“You must become someone else,” the small man continued, “for your own safety, and for the safety of your unborn child—”

“How did you know?” asked Rosetta, and immediately looked downward, blushing.

“There is a certain glow about you, madam, that the ruddy morning light alone could never provide. You will have to create for yourselves new identities unrecognizable to those who know you. You will have to become people other than yourselves. And you, sir,” he said to Andy, “will have to stop making those drawings.”

[to be continued]

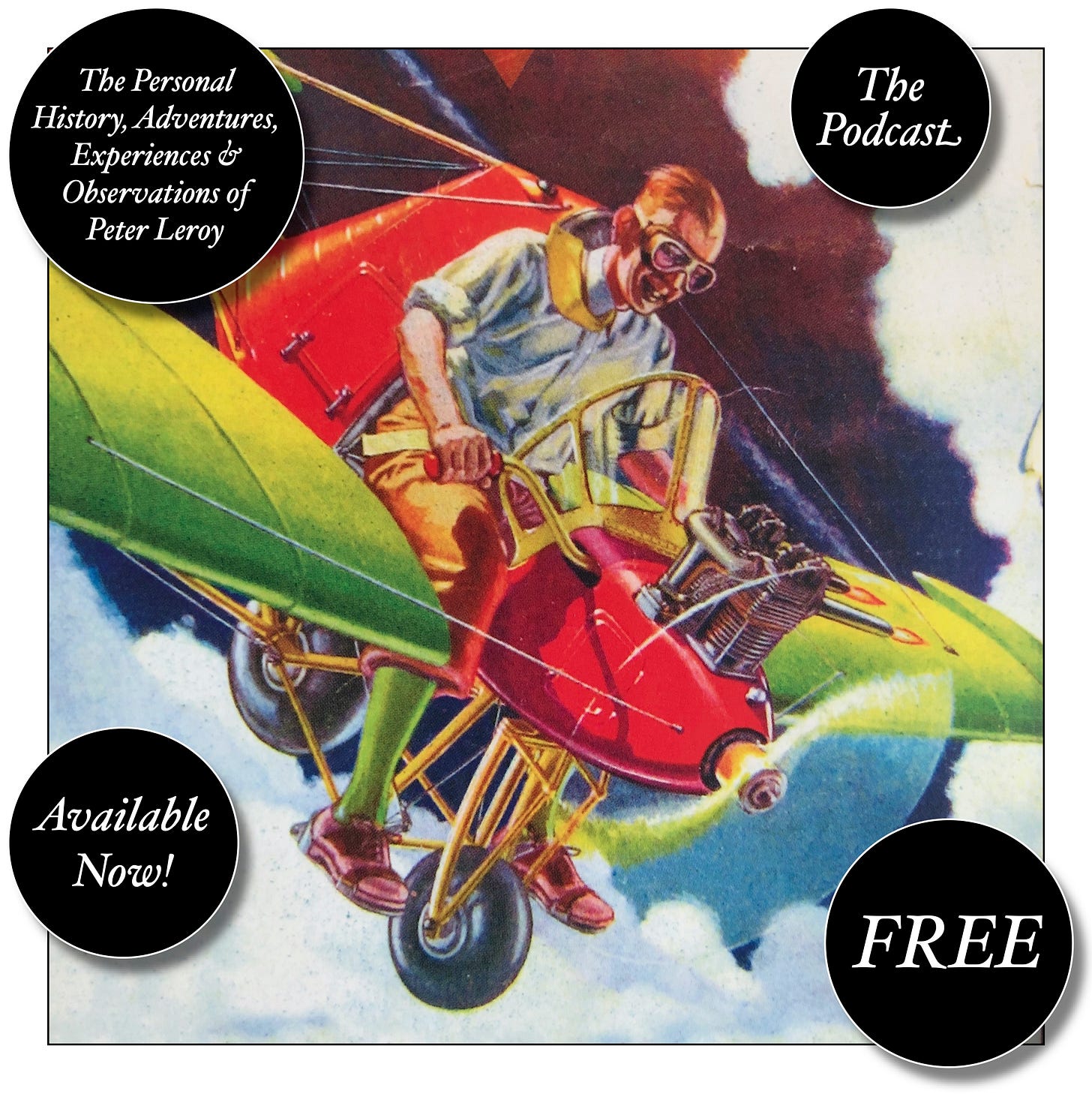

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.