28

WHAT DO I REMEMBER after that? Since I was so happily in a daze, I went where I was led. I have to be careful here not to fill the night with details from later memories, for I was to follow this route many, many times with the girls, and I have always had the tendency to want to fill in the blanks, to color every inch of the page, paint and overpaint. I want to try to re-create the path from paradise to the Glynns’ house, but the memory is so thin, so obscured by mist and befuddlement, that although I can feel them beside me vividly, feel their hands tugging at me, guiding me, and see their faces floating in the mist, I can’t distinguish much beyond them.

I remember a road, winding, wet with fog, trees here and there, a margin of grass beside the road. This was a prosperous part of town, so dedicated to the cult of clipped and even lawns that the homeowners zealously weeded and trimmed the roadside strip that belonged to the town—but, you see, I’m filling in. I thought about none of that at the time. Did I see mailboxes? No, I’m filling in again, but I feel the girls’ hands, that sensation I’m certain of, and I see their bouncing hair, their little ears, the earnest expressions in their glances—glances at each other, at me, backward—and I remember that I admired their devotion to the game.

(Watching from a distance, from so much later, I see a boy with a grin, being led, and although the little guy is right to admire the girls’ devotion to their game, his older self is happy to admit that at the time he didn’t have the faintest idea what game they were playing.)

“Here we are,” said Margot.

“Oh,” said I, astonished. “You’re right.”

I was quite disappointed. I had lost all notion that there would be an end to our route. I would have been happy to have kept walking, just kept walking, with them beside me and me in my daze, blissful and befogged.

“I guess—” I began, and I was going to say that I’d better go home, but found that I didn’t want to go.

“Come on,” said Martha.

She began tugging me toward the side of the house, away from the street lamps, into the dark, but responsibility was pulling me the other way.

“I have to go,” I said.

“They’re not expecting you at home,” said Margot.

She began shoving me around the side of the house.

“I called your mother earlier today, when you were on your way to our house. I told her that Our Father thinks you’ve got talent. He was raving about some of your drawings—”

“He was?”

“No.”

“Huh?”

“This is what I told your mother.”

“Oh.”

“When he saw your sketches, he insisted that you stay for his regular drawing class, the night class, stay overnight, go home in the morning.”

“That’s what you told her?”

“That’s what I told her.”

“What did she say?”

“She said okay.”

“She let me stay without my toothbrush?” I said.

“She thinks Our Father thinks you’re a genius.”

Even in the midst of all that was happening to me I had a momentary image of my mother on the other end of the phone, listening to Margot, and smiling in surprise, and I knew that my mother would have been imagining a future for me as an artist, that she would probably even have been imagining—in a hazy way—some of the pictures I would eventually paint. I was thinking along similar lines myself, but the girls wanted me in a different dream.

“Is that a car?” whispered Martha, back in the getaway game.

“Yes!” said Margot. “Come on, Peter. Come on.”

They led me at a run to the back of the house.

“You go up here,” said Martha, pointing, whispering. “Climb onto the top of the wall, go over to the corner, under that window, and up the ladder.”

“What ladder?”

“You’ll see,” said Margot.

“See you in a few minutes,” said Martha. “Be patient.”

They trotted off, around the corner of the house. I heard the front door bang, and, imagining myself as Rocky in the film, climbed up onto the little shed that sheltered the trash cans, clambered onto the wall that enclosed the courtyard, and walked along the wall to a corner of the house, where I waited. In a little while, the window of the girls’ bedroom opened, and from it a rope ladder fell onto my head.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

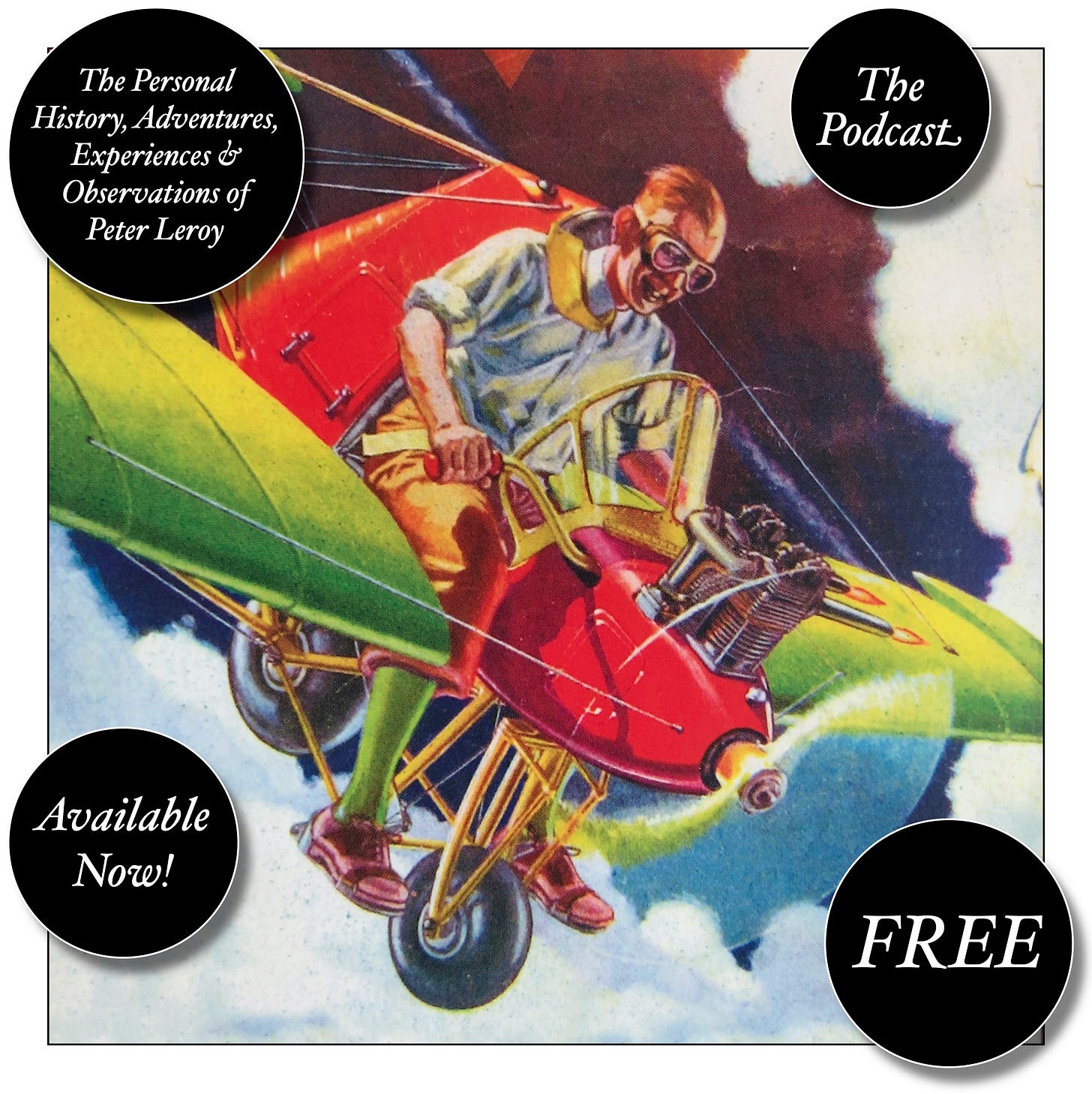

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post