“Now answer this if you can: What shape is a watermelon?”

Almost without thinking, I moved my hands into position to hold a nonexistent watermelon. “Well—” I said.

“I mean exactly what shape is a watermelon?” said Andy.

I hefted the watermelon.

“Well—”

“You can’t say, can you?”

“I—”

“And yet you must know, because when you see something that approximates that shape, then you say to yourself: that’s a lot like a watermelon—in fact, that is a watermelon.”

I looked at the empty space between my hands and said, “Mm.”

“All right. Now suppose I had a device that would implant a number of little pellets at random locations within watermelons.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I obtain many watermelons and use my device on them. I have a way of describing the location of each pellet in each watermelon.”

“But how would you be able to tell where each pellet—”

“I have a way of telling where each pellet is even though I can’t see through the watermelons.”

“Wow. How do you do that?”

“Peter, I began by saying ‘Now suppose,’ remember?”

“Oh. Yeah.”

“All right. Now suppose I have a way of telling where each pellet is within each watermelon, and suppose I have a way of describing the location of each pellet in each watermelon.”

“Okay.”

A look came over him that made me think he might giggle, and he went on in a great rush. “When I collate the locations of very many pellets in very many watermelons, I have a description of the shape of the ideal watermelon, the archetypal watermelon of which each of my samples was a more or less inaccurate approximation, but toward which the aggregate of watermelons, the summation of watermelons past, present, and future, tends.”

“Holy mackerel.”

Tugging at his gray moustache and snickering, he took hold of my collar and led me to the table where he kept his paints and rollers and roller pans. On the table there was a shrouded something shaped a lot like a watermelon.

“Voilà!” he said, plucking off the shroud.

There it was: the watermelon, lying there cool and green and striped, the perfect treat for a languid August afternoon, for the languid August afternoon. It put me in mind of one hot August afternoon in particular, when I was seven or eight, lying on my back in a field, with a kite string in my right hand, shading my eyes with my left hand while I watched the slow progress of a blimp—also shaped a lot like a watermelon—and wishing that I had something cold and sweet and wet, without quite knowing exactly what cold, sweet, wet treat I wanted. Here it was. Years later, I had found what I wanted: the watermelon of all watermelons. I put out my hand to touch it, wondering if we might slice it up as some sort of celebration. Swiftly but without malice Andy caught my hand, smiling as a keeper might, having prevented his idiot charge from thrusting his hand into a fire.

“It’s real,” he said.

“What?”

“It’s a real watermelon. Rosetta got it at the market.”

“The Babbington Market?”

“Yeah. It’s just for demonstration purposes. I just wanted to make my point.”

“It’s really—you know—a good one.”

“Exactly my point. A very close approximation of the ideal.”

“I get it.” I was terribly disappointed, but I didn’t let it show.

“Well, as you guessed earlier, I don’t have a device that implants pellets in watermelons, and I don’t have a device that can describe the locations of pellets in watermelons. But you do. And so do all of my students. At least they think they do. I knew that I could set the students to sketching some simple object from memory and observe its transformations at their hands. With enough samples, I could codify the diversity of their misinterpretations and work my way back to the underlying ideals. You can see that, can’t you?”

“I guess so—”

“For months I searched for suitable objects, things that would be simple to sketch but that admitted of interpretation, things that altered in the mind of the beholder. I finally settled on several.”

He gave a chuckle.

“A watermelon, of course, and an egg, an orange, a baseball, a potato chip, a clam—thanks to you—a pea—thanks to you again—and so on.”

He began laying sketches out on the floor.

“I really think I’m getting somewhere,” he said.

He may have been right, but I couldn’t tell some of the clams from some of the watermelons.

[to be continued]

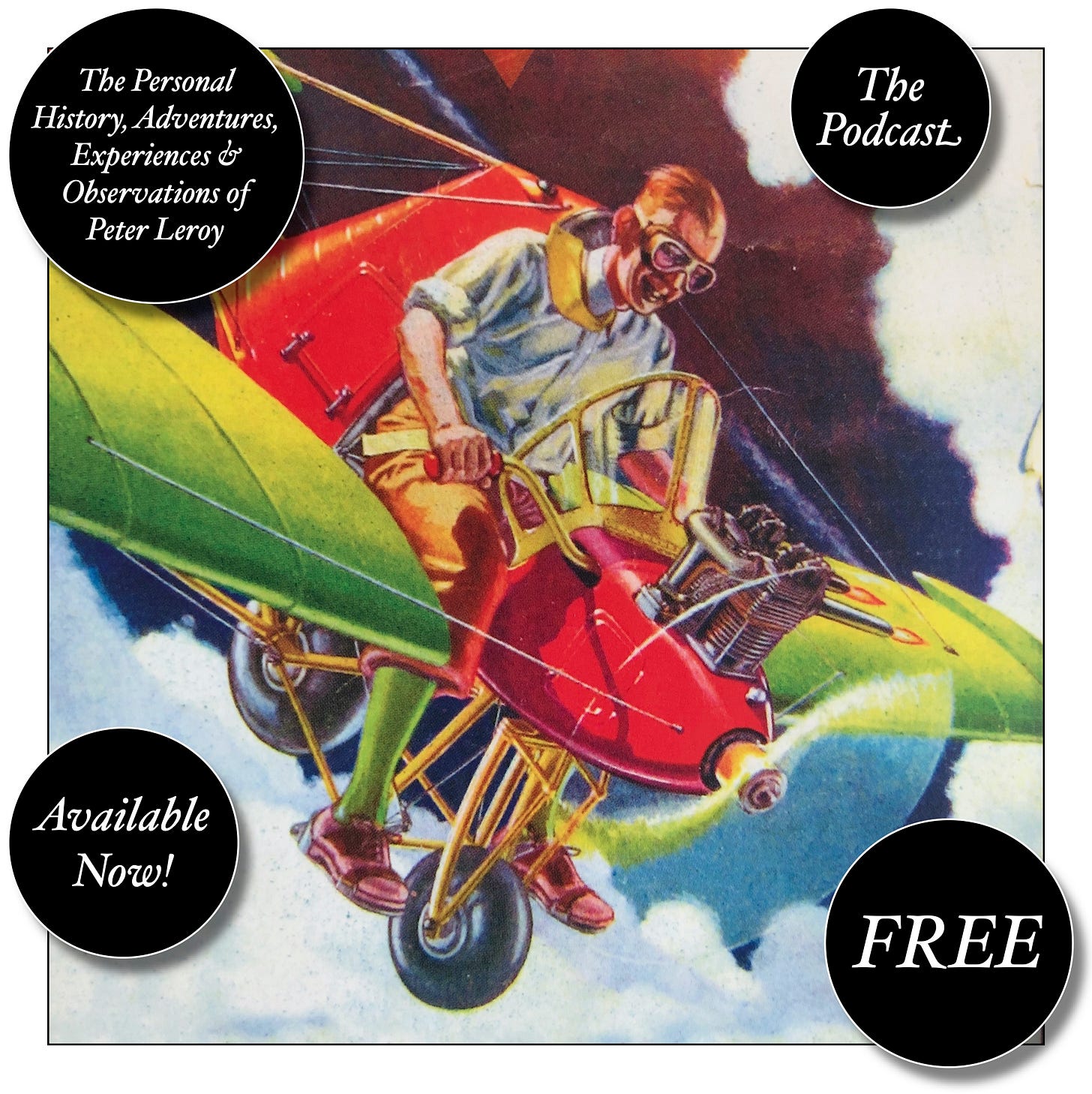

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post