36

“I ENJOY MY WORK as I never did before,” said Andy. “I don’t mean the painting, though I still do it—it’s a living. And I don’t mean the teaching—that’s just a means to an end. I mean my study of the archetypal images that control our view of the world. In that study, I have found my work. This is what I was meant to do.” He bent over the drawings, examining their minutest deviations from ideal models, shaking his head with amazement at the rightness of fit between him and his vocation. At last he straightened up and looked at me.

“However,” he said, “I’ve got a problem.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Actually, I have several problems, and I think you can help me with them.”

“Okay.”

“It all starts with the students. Almost from the beginning I detected an attitude of dissatisfaction among them. They drew what I told them to draw, but they invested very little in their work.”

He studied me for signs of understanding.

“They weren’t trying hard enough,” he said.

“Oh.”

“My study suffered from their lackluster application. The junk they were turning out was so far from ideal that sometimes I couldn’t tell the clams from the watermelons.”

“I had the same—”

He held a hand up and continued: “If they weren’t making a real effort to represent what they saw with their minds’ eyes, I couldn’t be sure that the drawings held the clues I needed to find the underlying archetypes, could I?”

“No.”

“Not only that, but attendance began falling off.”

“How come?”

“They weren’t satisfied with their own work—though I didn’t realize it at the time. I thought they just weren’t enjoying themselves. I tried to be more accommodating. I’m not a very good host, but I made an effort. One week, I passed a dish of candies around, and that seemed to please them, so I thought food might be the secret, and the following week I instituted a tea break. The tea was served by Margot and Martha, who had just come home from their ballet lesson. They were in their leotards, and a little sweaty, and—well—you get the picture.”

I did. Two nymphs fresh from their exertions at the barre, their foreheads still dewy with the effort, their cheeks a little flushed, a damp strand or two of hair awry, the fabric of their leotards plastered to their limber bodies.

“Ah, yes,” I murmured.

“What?”

“Nothing. Go on.”

“A new interest was generated at once—”

“I’ll bet,” I said before I could stop myself.

“I didn’t mind,” said Andy with a shrug. “I didn’t mind at all, since I welcomed anything that would keep the students coming and keep them generating data for my studies, but as the weeks went by the tea breaks began to extend and to assume an importance that annoyed me, and drawing lost its status as the point of the evening’s gathering. It became an annoying requirement, a hurdle to be leaped, on the opposite side of which stood my daughters, their teapot, and a plate of macaroons.”

“Wow.”

“Not only didn’t the students put any more effort into their work, but now they also did their work in haste. It was careless, shoddy, useless for my studies, completely useless. I’ll tell you frankly that for a while I was tempted to abandon the whole scheme, and if I hadn’t come to realize that this is my life’s work, I would have.”

“Gee.”

“When the lesson was over and the students were gone, I would come into the studio and ask myself, ‘What to do? What to do? What to do?’ One night, I tried putting myself in their shoes, pretending that I was one of my own students, to see what they were thinking while they were working, and while I was standing at one of the easels making a halfhearted stab at drawing a potato, I found myself continually looking at the studio door, wishing that the girls would come through that door, bringing the tea, and then, just at that moment, I anticipated the request that none of the students had yet had the nerve to make.”

He looked at me, inviting a response. This seemed to me a good time to respond with a blank look, and that’s what I did.

“Oh, come on,” he said. “You see what I’m getting at.”

I looked puzzled.

“They wanted the girls, so I gave them the girls.”

“Oh!” I said. “I get it.”

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

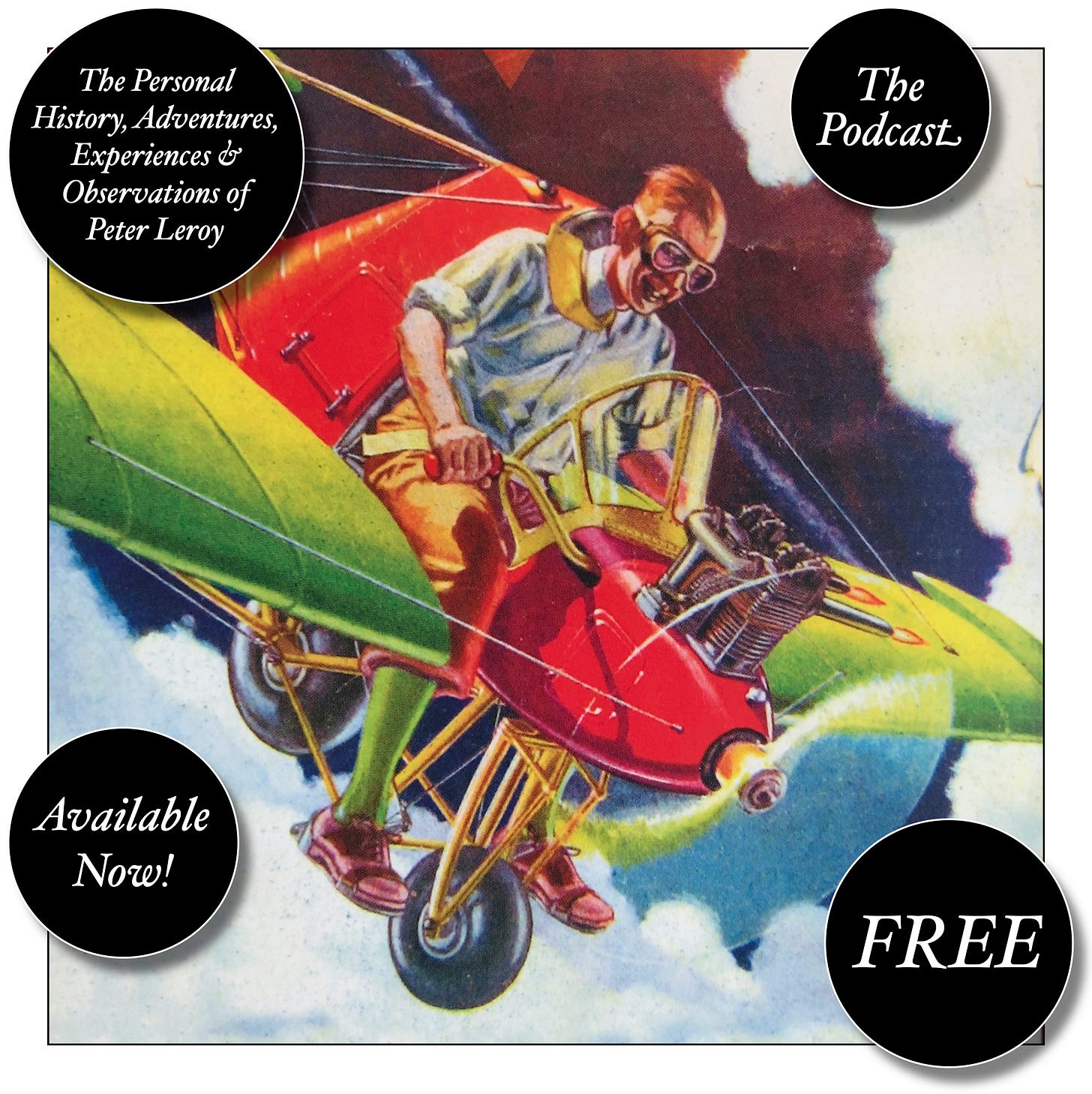

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop? and What a Piece of Work I Am.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.