When and why did I begin reviewing, reconsidering, and revising my life? I’d like to tell you the origin story, fully and frankly. However, to be able to give you a full and frank report I’d have to put myself back into the mind of my younger self, and that is as difficult—maybe as impossible—as putting myself into the mind of another person, or a bat, or a parrot. I’ll make the effort, but I admit that I’m going to invent what I can’t remember. Here I go.

I find myself sitting at my desk in my bedroom. I think I might be eleven or twelve. My father made the desk I’m sitting at. We had a troubled relationship, but I remember the gift of that desk as a kindness. I was grateful for it then, and I’m grateful for it now. Sitting at that desk, back then, back there, I’m trying to design the cover of a magazine. I have no clear idea what will be in the magazine, but I’m hard at work on the cover. Why? I’m not quite sure. I can’t perceive my motive. I think my younger self is trying to conceal it from me.

I know now—and I suspect that my younger self knew then—that I wanted everything in the magazine to be about me. Even at the time the idea embarrassed me. That embarrassment may eventually have led to my turning to writing about others as well as myself—but all the others were aspects of me. They still are.

Consider, for example, Bertram W. Beath.

BERTRAM W. (“BW”) BEATH was waiting for the beautiful Miranda at the museum where he and she had arranged to meet. She was a few minutes late, and he was beginning to expect that she—but suddenly there she was—radiant, lovely, and a little out of breath.

“I bought myself a pair of black leather boots,” she said. “See?”

“No,” said BW, because the boots were in a box and the box was in a bag.

“I’ll show them to you later,” Miranda said. She winked.

“Hmmm,” said BW.

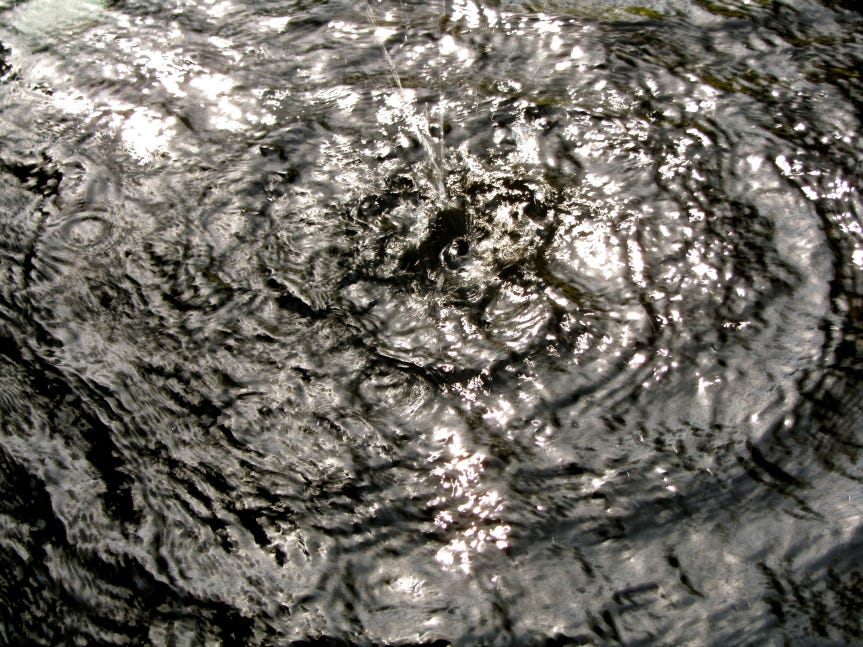

They spent an hour at an exhibition of selections from four decades of the museum’s holdings of contemporary art. At one point, they were examining “Water,” a series of photographs of water. They were beside another couple who were examining the photographs of water. “I like these,” said the woman in the couple. “They could be abstractions, but because they’re not abstractions, there’s something deeper to them. They make me see something obvious that I haven’t given the attention it deserves.”

The man in the couple said, “I could make photographs like these. In fact, I could have made these.”

BW said to Miranda, “How about a drink?”

They had a drink at the bar in the museum’s restaurant, and then, in the museum’s auditorium, they watched a showing of a film called I Love a Parade. For fifty-eight minutes, they saw people in a city pass by on a sidewalk. The people were filmed so that their faces were never seen, just the sidewalk, their legs, their feet, and their shadows. The sound was the ambient sound of the street, including snatches of the conversations of the people who passed. The museum had billed it as “a stunning work of high seriousness and great verve.”

“What did you think?” Miranda asked while they were walking to dinner.

BW grinned and said, “It made me see something obvious that I haven’t given the attention it deserves.”

Miranda gave his arm a playful punch.

Then he said, “I could make a film like that. In fact, I could have made that one.”

AT THE RESTAURANT they’d chosen, Miranda set the bag that held the boots on the banquette beside her.

The woman in a couple seated beside them said to her companion, “The way I see it is I’m on like a quest.”

“Mmm,” said her companion. He tapped at his phone.

“It’s like I’m either going to find what I’m after or I’m going to like kill myself.”

“Uh-huh,” said her companion. He set his phone down and placed his hand on hers.

Miranda and BW ordered. They chatted. They were served. They ate. Their waiter approached their table and asked, “Would you like anything else?”

“I’d like to see Miranda in her new boots,” said BW.

Miranda giggled.

“I’ll bring the check, then,” said the waiter.

AT BW’s APARTMENT, Miranda excused herself and slipped into the bathroom.

In a couple of minutes, she emerged, wearing the boots and nothing but the boots. She stood there. BW stood across from her. She stared at him. He stared at her.

Finally, she took a couple of steps toward him and said, “Well?”

“Miranda,” he said, “there is something I want to ask you.”

“Yes?” she said, arching an eyebrow.

He cleared his throat. “Are you real?”

“Am I real?” she asked with a nervous laugh. “I certainly think so. Don’t you?”

“Yes and no,” he said. “You’re so perfect for the part of the beautiful Miranda that I sometimes wonder whether I’ve imagined you.”

“Take me to bed,” she said.

A WEEK LATER, BW and the beautiful Miranda were witnesses to a theatrical production in which two actors portrayed a dozen characters, following which, at a restaurant around the corner from the theater, they found themselves seated beside two other witnesses to the same production, one of whom was saying, “I can admire their virtuosity, but their emotional investment in the characters—and therefore my emotional investment in the characters—was stretched so thin that I didn’t feel that even one of them was—you know—real.”

Hearing that, BW glanced around the room. He found that he had no emotional investment at all in any of the characters around him—other than Miranda.

“You’re right,” the woman’s companion said. “They never quite managed to make any of the characters fully convincing—but I have seen that sort of thing done well. I remember seeing two actors who succeeded brilliantly in portraying what seemed like the entire population of Ireland.”

“I remember that, too,” the woman said.

“Really?” the man said. “Were you with me? I don’t seem to remember that you were.”

Instead of replying, the woman attacked the saucisson that had been brought to them as an hors d’oeuvre.

After a while, the man said, “Something is bothering you.”

“Why do you say that?” she asked.

“You’re attacking that sausage as if it were a threat to your way of life.”

She looked at the sausage. She looked at the knife that she was holding. “Put a sharp knife in my hand,” she said, “and I think of doing something nasty to the woman who lives down the hall from me.”

“Why?” he asked.

“Because she is keeping a dog in her apartment—the short, fat kind that looks as if it’s just eaten something putrid.”

“A pug,” said the man.

“By signing the lease she agreed that the building is a dog-free zone. Her violation of the rule is an example of the lack of fellow-feeling that sets people against one another, and it infuriates me.”

The man drew a breath, let it out, and said, slowly, “I’ve always thought of a solipsist as a peculiar type of fool who thinks of himself as a creator imprisoned in his own creation. Increasingly, I find that the description fits me very well. I blame myself for building the cage I find myself in. Why have I? Why am I in this cage? Why am I a solipsist?”

BW began looking for a waiter and wondered, as always, why there never was one when he wanted one.

The question was, What to write about? . . . I had read that one writes because one has something to say. I could not see that I had anything to say except that I was alive.

V. S. Pritchett, Midnight Oil

Our own experience provides the basic material for our imagination, whose range is therefore limited. It will not help to try to imagine that one has webbing on one’s arms, which enables one to fly around at dusk and dawn catching insects in one’s mouth; . . . and that one spends the day hanging upside down by one’s feet in an attic. In so far as I can imagine this (which is not very far), it tells me only what it would be like for me to behave as a bat behaves. But that is not the question. I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat.

Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” (1974)

He always liked to spread his meals out, to make them last longer. A drink of water to wash the food down, and he returned to the middle of the cage, where he proceeded to conduct a few intimate researches with his beak under his left wing. After which he mewed like a cat, and relapsed into silent meditation once more. He closed his eyes and pondered on his favourite problem—Why was he a parrot?

P. G. Wodehouse, Jill the Reckless

The problem of other minds is the problem of how to justify the almost universal belief that others have minds very like our own.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition)

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading the Personal History at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future episode by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.