ONE DAY, while Madeline and I were strolling arm in arm through Central Park, that island of greenery in New York’s urban environment, playing the part of a couple from the nineteenth century, I found myself thinking about realism, not from a reader’s or critic’s point of view but from a writer’s point of view; that is, as a set of aspirations and techniques employed by writers—or other artists, for that matter—rather than as a result of those aspirations and techniques. During the ensuing days and weeks, I found myself wondering more and more about the aspirations of writers—particularly Henry James—who use the techniques of realism to create the illusion of reality as a cloak for a romance.

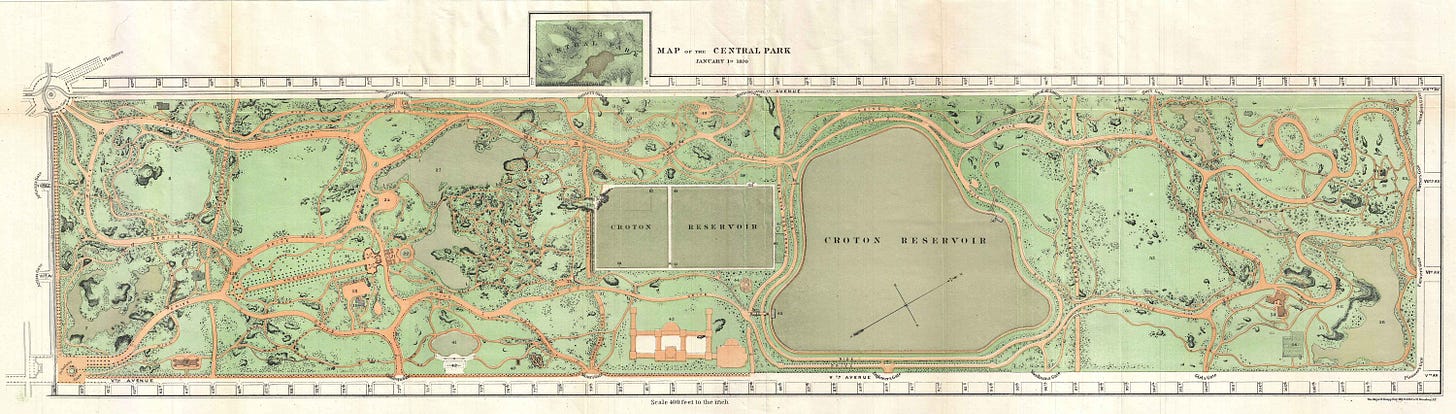

THE CENTRAL PARK SETTING suggested that a revealing comparison might be made between the aspirations of such writers and the aspirations of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who designed the landscape. Parts of the park announce themselves as urban and planned, but other sections—in particular “The Ramble”—seem to have been left in a natural state, as bits of wilderness in the heart of the city. The truth is that all of Central Park is an artificial environment, with false hills, false lakes, and imported trees. It is a distillation of nature—naturalistic, but not natural.

In parts of the park, I think I can detect the designers’ desire to create a work that would inspire the awe and wonder and joy that nature inspires, and to achieve that effect in a more compact and richer way than nature herself ordinarily does. To bring a taste of the sublime to the urban stroller on a rushed lunch break requires a landscape more than real, enriched by concentration, like a sauce made by reduction.

Olmsted envisioned the Ramble as a romantic “wild garden.” After the terrain was cleared of undesirable stone and plant life, and after its swampy wetlands were filled, a forest of richly varied trees, shrubs, and flowers was planted. A stream was created and made to wind through the landscape, forming pools and splashing down rocky slopes before emptying into the Lake. Charming paths, rustic bridges, a mysterious cave, an ancient-looking stone arch, and exotic birds . . . provided additional fairy-tale touches.

Richard J. Berenson and Raymond Carroll, The Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park (Sterling, 2008)

In the case of our Park it must be remembered that for the site on which it was decided to plant it, nature had hardly expended the slightest effort. . . . A more unpromising locality was never given to any Adam to make an Eden of, and few persons who have not watched the progress of the Park from its commencement can fully understand that its present condition is almost entirely an artificial product. Nature having done almost nothing, art had to do all. And yet art . . . has been able to produce a result, which, on the whole, so closely resembles nature, that it is no wonder if the superficial observer does not clearly see how vast is the amount of work that had to be performed before the Park could reach its present perfection. Nowhere in the Park, as it seems to us, has the result achieved been more worthy of the money, labor, and thought expended to produce it, than in the Ramble. Here at least we may be thankful that the Commissioners have not been content with merely “letting alone.” For the Ramble is, in almost every square foot of it, a purely artificial piece of landscape gardening. Yet the art of concealing art was hardly ever better illustrated.

Clarence Cook, A Description of the New York Central Park (New York: F. J. Huntington and Co., 1869)

HENRY JAMES explained his view of the difference between realism and romance in his preface to the New York Edition of The American in 1907. There he said that romance deals with

experience liberated, so to speak; experience disengaged, disembroiled, disencumbered, exempt from the conditions that we usually know to attach to it and, if we wish so to put the matter, drag upon it.

In a lighthearted image, he likens the effect of romance to the lifting power of a lighter-than-air balloon:

The balloon of experience is in fact of course tied to the earth, and under that necessity we swing, thanks to a rope of remarkable length, in the more or less commodious car of the imagination; but it is by the rope we know where we are, and from the moment that cable is cut we are at large and unrelated: we only swing apart from the globe—though remaining as exhilarated, naturally, as we like, especially when all goes well.

Then he turns to the art of the romancer:

The art of the romancer is, “for the fun of it,” insidiously to cut the cable, to cut it without our detecting him.

However, he goes on to contradict himself somewhat, because he says that for the reader of a romance there remains

. . . our general sense of the way things happen—it abides with us indefeasibly, as readers of fiction, from the moment we demand that our fiction shall be intelligible; and there is our particular sense of the way they don’t happen, which is liable to wake up unless reflection and criticism, in us, have been skillfully and successfully drugged. There are drugs enough, clearly—it is all a question of applying them with tact; in which case the way things don’t happen may be artfully made to pass for the way things do.

He seems to say that the reader, even if skillfully and successfully drugged, must be allowed enough contact with the reassuring earthly sense of the way things happen to keep the fiction intelligible.

I THINK that many artists—including writers who are romancers—are tempted to show the audience—or at least that part of the audience that is worthy of the favor—how the trick is done, how the art is made, how the cable has been cut so tactfully and insidiously that the cutting has gone unnoticed. Why do I think that? Because in the company of some writers, after a few drinks, I have heard them discourse on the power of that temptation and describe with glee specific times when they have given in to it. Having thus been alerted to the phenomenon, I have become quite good at spotting it in print. For example, while I was rereading James’s The Bostonians, this passage brought me up short:

Basil Ransome lived in New York, rather far to the eastward, and in the upper reaches of the town; he occupied two small shabby rooms in a somewhat decayed mansion which stood next to the corner of the Second Avenue. The corner itself was formed by a considerable grocer’s shop. . . . The house had a red, rusty face, and faded green shutters, of which the slats were limp and at variance with each other. . . . The two sides of the shop were protected by an immense penthouse shed, which projected over a greasy pavement and was supported by wooden posts fixed in the curbstone. Beneath it, on the dislocated flags, barrels and baskets were freely and picturesquely grouped; an open cellarway yawned beneath the feet of those who might pause to gaze too fondly on the savory wares displayed in the window; a strong odor of smoked fish, combined with a fragrance of molasses, hung about the spot; the pavement, toward the gutters, was fringed with dirty panniers, heaped with potatoes, carrots, and onions . . .

The passage struck me so forcibly because it was the first time in my rereading that I had encountered James using techniques of realism so directly. I hadn’t found much of this kind of realistic precision elsewhere in his work, but this passage has the vividness and accuracy of a photograph.

Let me quote further, because I soon found James giving the game away, winking at the reader, and displaying the rope that holds the balloon:

I mention it not on account of any particular influence it may have had on the life or the thought of Basil Ransome, but for old acquaintance sake and that of local color; besides which, a figure is nothing without a setting, and our young man came and went every day, with rather an indifferent, unperceiving step, it is true, among the objects I have briefly designated.

James has, for reasons of his own, chosen to tell us that what we have read about the decayed mansion on Second Avenue and the grocer’s shop on the corner next to it isn’t part of the romance at all. It’s there to satisfy what he referred to as “our general sense of the way things happen.” The shop is one of the spots where the rope of the balloon of romance was tethered to the earth before the rope was cut . . . and here he is at least momentarily tying it back to its mooring there . . . just to show us that he can.

WHAT MIGHT Basil Ransome’s New York have looked like? Well, it would have looked something like what we see in the images of New York in the Nineteenth Century that follow.

These images do not float free. They are solidly tied to the earth, and the rope that ties them is short and sturdy. You would have to work hard to cut these images free. They do not show disconnected and uncontrolled experiences: they depict experiences that are entirely controlled by our sense of the way things happen. Or do they? We’ll return to that question a little later.

WHEN I THINK of realism in literature, I think of Balzac, of course. One mark of Balzac’s realism—one that I think of as an essential element of realism—is an interest in the broadest possible range of the real world out there, including its people, their occupations, their lives, their travails, their burdens, and their stories. In this, in his range, Balzac is unequaled.

In contrast, James’s world, the world of James’s work, is almost laughably narrow. Ignoring for a moment Basil Ransome’s neighborhood, it is a moneyed world, peopled largely by snobs who disdain anyone whom they consider vulgar. They seem almost to have a fear of vulgarity, as if it might be catching.

James knew himself as a romancer, but he also knew that he owed a large debt to Balzac because it was from Balzac’s work that he learned the techniques of realism, the techniques that James used to lend verisimilitude to his romances.

Balzac, in contrast, had a real desire to document the life of his times, the way things happened, as well as to tell romances about the way things didn’t happen. Balzac was not “a documentarian,” as the sneering writer of an introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of one of James’s novels called him, though he was adept at the techniques of documentary.

James makes a reference to Balzac in the scene in The Princess Casamassima in which Hyacinth calls on Lady Aurora, at her invitation, to choose some books to borrow. James writes that

There were certain members of an intensely modern school, advanced and scientific realists, of whom Hyacinth had heard and on whom he had long desired to put his hand; but, evidently, none of them had ever stumbled into Lady Aurora’s candid collection, though she did possess a couple of Balzac’s novels, which, by ill-luck, happened to be just those that Hyacinth had read more than once.

Is James saying here, “I’m no Balzac, and I neither pretend to be nor desire to be”? Maybe. Let’s come back to that question.

NOW I want to make a distinction between art and documentary, between an artist and a documentarian.

For a definition of art, I’ll turn to Flaubert, who is, of course, widely regarded as a realist of the first order (though as we shall see shortly he ought to be regarded as a romancer who employed techniques of realism). Writing to Louise Colet on August 26, 1853, Flaubert said:

I am devoured now by a need for metamorphoses. I would like to write everything I see, not just as it is, but transfigured. An exact account of the most magnificent real fact would be impossible for me. I would still need to embroider it.

In The Perpetual Orgy, his wonderful book about Flaubert and Madame Bovary, Mario Vargas Llosa pointed out that that remark sums up the relation between fiction and reality in what he called “novelistic creation”:

the point of departure is real reality (“everything I see”), life in the broadest sense . . . but this material is never narrated “exactly”; it is always “transfigured,” “embroidered.” The novelist adds something to the reality that he has turned into work material, and this added element constitutes the originality of his work, that which gives autonomy to the fictional reality, that which distinguishes it from the real. [translated by Helen Lane]

To put that in James’s terms, returning to his floating balloon, the added element is what lifts the work above vulgar reality, things as they happen, and takes it into the realm of romance, things as they don’t happen.

So, I take the aspiration of the documentarian to be: to present or to communicate in some form things as they happen, or as they happened. And, in contrast, I take the aspiration of the artist to be: to transform things as they happen or happened into things as they don’t happen or didn’t happen.

Why does a documentarian attempt to record and present things as they are or as they were? One motive is preservation, obviously, and another, probably just as obviously, is propagation, publication in the sense of bringing to an audience something that the documentarian has observed or discovered, as we do when we take snapshots on our vacations and force our friends to look at them.

The photographer of this souvenir view of the Avenue de l’Opéra had those motives, I think.

The Neurdein brothers began their photographic career in 1863 in Paris, at 8 rue des Filles du Calvaire. . . . In 1868 we find [them] at 28 Boulevard Sevastopol. This is the beginning of the prosperity of the Neurdein House, whose production is such that they are obliged to hire photographers who harvest images for them in France, and soon the whole world. Production is eminently for commercial purposes. The tourist finds, in all the resorts or remarkable sites, small notebooks containing a dozen or fifteen photographs in miniature format representing the main views of which he wants to keep the memory.

Yves Lebrec, “Neurdein Frères,” yveslebrec.blogg.org (freely translated and lightly edited)

The camera was made of black plastic, the kind called Bakelite. . . . When one held the camera with the viewfinder to one’s eye, the forefinger of one’s right hand fell quite naturally on the shutter button, and the middle finger fell quite naturally over the right half of the lens. I loved that camera. I carried it with me everywhere. . . . But as much as the camera pleased me it intimidated me. A statement in the instruction booklet said, “Snapshots will capture your memories forever,” and I understood at once that the snapshots I was likely to take would capture forever memories of my childish ineptitude as a photographer, the evidence of my awkwardness and uncertainty. Clearly, the wise thing to do would be to avoid using film until I had acquired some poise, if only enough so that I wouldn’t take pictures I would really regret, so I put the film in the back of my sock drawer to save until I felt confident enough to use it.

Peter Leroy, “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” in Little Follies

Why does an artist transform things from the way they are or were to some form in which they are not or were not? One motive is to have an effect on the world, to make it a little less the property of everyone else and a little more the property of the artist. Another is to play god a little bit, to make a world more in the artist’s image than this one is. And another is to beguile an audience, to enjoy a host’s pleasure at giving them an entertainment, a ride in one’s balloon.

In painting this view of the Avenue de l’Opéra, Camille Pissarro had those motives, I think.

Was Balzac a documentarian? No. He was an artist who used the techniques of documentary in the service of romance. When he was assiduously preserving the manners and mores and methods and madness of France, of Paris and the provinces, he was documenting a France that Balzac the artist had already transformed, had already lifted a certain distance above the France of Things as They Happened—though it was anchored securely there, and then he tethered his romances to that other France, Balzac’s France.

Our own experience provides the basic material for our imagination, whose range is therefore limited.

Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” (1974)

No art without transformation.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematograph

THERE IS, as I suggested earlier, an impulse, a tendency, or a desire on the part of most artists—I’m tempted to say all artists—to pause in the work of being artful and say, “Look: this is what I’m really up to. I’m going to give you one quick look behind the scenes, let you see the way the props are made, sit down with you for a moment over a congenial glass and confess to you what it is that I want to achieve, and then I’m going to send you back to your seat and return to drugging you and deluding you.

Often, the urge to confess—or to show off—becomes so overwhelming that the artist gives in to it because it arises from a desire to tell or show the reader or audience where the artist’s balloon is tethered, as we saw James doing when he inserted his documentary description of the grocer’s shop into Basil Ransome’s New York.

Here is Marcel Proust, in Frederick A. Blossom’s translation, giving in to the impulse in the section of The Past Recaptured called “Charlus During the War.” First he introduces—with a wealth of documentary detail—some characters we haven’t met before:

One of Françoise’s nephews, who was killed at Berry-au-Bac, was the nephew also of those millionaire cousins of Françoise, former café owners who had made their fortune and retired a long time before. The nephew, also a café proprietor, but in a small way and with limited means, had been drafted at the age of twenty-five and had left his young wife alone to run the little bar which he expected to come back to in a few months. But he was killed. . . . The millionaire cousins, who were no relation to the young widow, left the country place to which they had retired ten years before and went to work again in the café business, but refused to accept a sou for their labor; at six o’clock every morning, the millionaire wife, a real lady, and her young lady daughter were dressed and ready to help their niece-in-law and cousin-by-marriage. And for more than three years, they had been rinsing glasses in this way and serving drinks from early morning till half-past nine at night, without a single day of rest.

And now he beckons to us and takes us to a place where the rope from his enormous balloon is tied to a stake driven right into the earth:

In this book of mine, in which there is not one fact that is not imaginary, nor any real person concealed under a false name, where everything has been invented by me to meet the needs of my story, I ought to say in praise of my country that, at any rate, these millionaire relatives of Françoise, who gave up their retired life in order to help their niece when she was left without support, are people who really are alive and, convinced that their modesty will not take offence because they will never read this book, it gives me a childlike pleasure and deep emotion to record here their real name, Larivière.

Well, do you believe him? I certainly don’t believe him when he says that in In Search of Lost Time there is not one fact that is not imaginary. I don’t believe that he intends me to believe him, either. I do believe that he wants me to understand that he has labored to make the people, the places, and the institutions in his story meet the needs of his story, and in doing so has brought them a long way from their real origins. And I do believe that to make his point he has inserted here, as little altered as he could make them, these real Larivières, to show me or to remind me that there is a difference between them and Françoise or Charlus, between people who live in the world and characters who live in a romance.

I had found myself awakened by a desire, the way I might have been awakened by the sun. . . . I wanted to learn to paint—really wanted to learn to paint. . . . I’d been sold on the idea by the matchbook advertisements distributed by the Past Masters Correspondence School, an outfit that offered instruction in everything from plumbing to poetry, all in the privacy of your own home, through lessons devised by professionals recently retired from the discipline of your choice. These lessons were very popular at the time. Smoking was also popular at the time, and the Past Masters used matchbooks to recruit their students. . . . The one for the taxidermy course showed a cartoon raccoon over the challenge “Stuff Me!” The one for plumbing showed a dripping faucet over “Stop Me!” The one that got me, the one for the art course, showed the profile of an attractive young woman over the challenge “Draw Me!”

Peter Leroy, At Home with the Glynns

NOW let’s take a look at Henry James succumbing again to the impulse to reveal the anchor for the tether on his balloon and this time also revealing his motive in launching that balloon.

In The American, originally published in 1877, Christopher Newman, the millionaire American of the title, falls in love with Claire de Cintré, but her family opposes their marriage. Her mother and elder brother conspire to destroy Newman’s chances by making the marriage an issue of her loyalty to her family and to the family’s illustrious lineage. Claire steps aside from the conflict by entering a convent. Newman is dumbfounded and heartsick.

This passage occurs in Chapter 24:

Sunday was as yet two days off; but meanwhile, to beguile his impatience, Newman took his way to the Avenue de Messine and got what comfort he could in staring at the blank outer wall of Madame de Cintré’s present residence [the convent]. The street in question, as some travelers will remember, adjoins the Parc Monceau, which is one of the prettiest corners of Paris. The quarter has an air of modern opulence and convenience which . . . suggested a convent with the modern improvements—an asylum in which privacy, though unbroken, might be not quite identical with privation, and meditation, though monotonous, might be of a cheerful cast. And yet he knew the case was otherwise; only at present it was not a reality to him. It was too strange and too mocking to be real; it was like a page torn out of a romance, with no context in his own experience.

I’m going to return to that final sentence in a moment, but I’d like to consider another sentence first:

The street in question, as some travelers will remember, adjoins the Parc Monceau, which is one of the prettiest corners of Paris.

If we may believe Joris-Karl Huysmans, who used an abundance of documentary detail in his fiction, the convent did exist at number 23 Avenue de Messine. Here is his summary of its history from De Tout, published in 1902:

Le dernier Carmel de Paris est enfin situé au no. 23 de L’avenue de Messine; il est la seule maison de cette avenue, bordée de constructions de luxe, qui soit propre; il apparaît recueilli et charmant, dans sa petite robe gothique, au milieu de tous ces hôtels qui s’alignent, prétentieux et rigides, neufs et bêtes. Ce Carmel qui touche presque au parc Monceau, a derrière lui un grand jardin dont les murailles s’aperçoivent . . . dans le square de Messine.

Here is my translation of the passage, which I ask you to read in a forgiving frame of mind:

The most recent Carmelite convent in Paris is situated at Number 23, Avenue de Messine; bordered by deluxe structures, it is the only house that seems appropriate to that avenue; it appears composed and charming, in its modest Gothic raiment, in the midst of all these pretentious and stiff, new and beastly mansions that are lined up beside it. This convent, which nearly adjoins the Parc Monceau, has behind it a large garden whose walls are visible . . . from Messine Square.

I think that we can believe Huysmans on the subject of the convent, because the Société historique et archéologique des VIIIe et XVIIe arrondissements de Paris reported in its Bulletin of 1905 that “M. Le Senne nous a retracé l’existence effacée et si courte du Carmel de l’Avenue de Messine, auquel Huysmans dans son livre «De Tout» a consacré des pages à la fois si mystiques et si réalistes.” That is, “M. Le Senne outlined for us the brief and obscure life of the Carmelite convent on the Avenue de Messine, to which Huysmans in his book De Tout devoted several pages that were simultaneously very mystical and very realistic.” (The modest Gothic convent building was, apparently, replaced in 1907 by a private mansion designed by the art nouveau architect Jules Lavirotte. Its size and the richness of its sinuous decorations would not, I imagine, have pleased Huysmans.)

There stands poor Christopher Newman, staring at the blank wall of the convent, very near the Parc Monceau, but as far as we can tell from James’s text, Newman doesn’t even know that the park is there. He is not a well-traveled man; he is certainly not among those travelers who would know that a short walk along the Avenue de Messine would lead to the Parc Monceau, “one of the prettiest corners of Paris.” Had he known so, he might have walked there and sought some solace in the beauties of the park, but I doubt that he would have; he wouldn’t have left the convent and the bleak comfort that staring at its wall offered him.

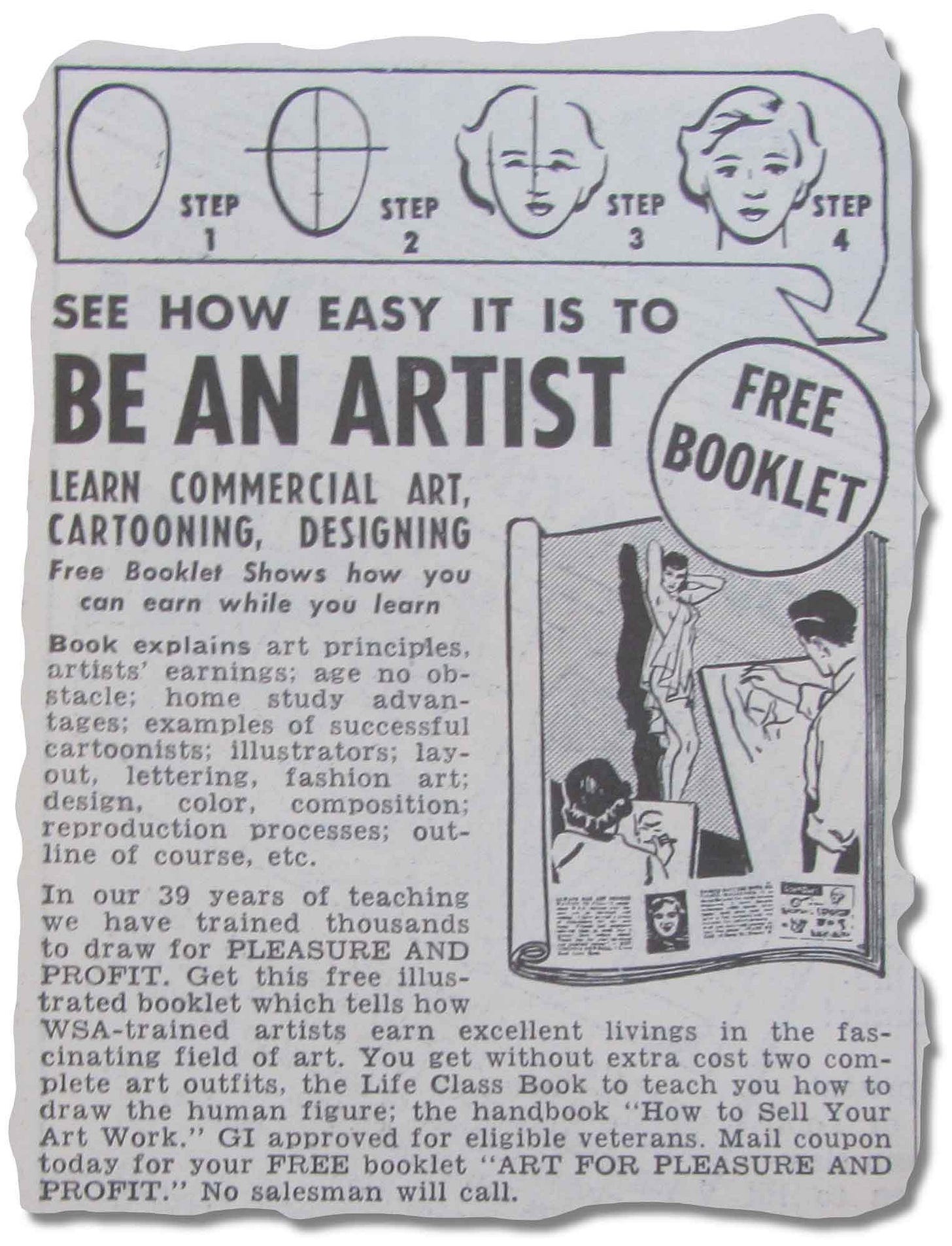

What sort of place is this Parc Monceau? Why does James include it in the setting for Newman’s visit to the convent? Here is a description from the “Monuments in Paris” website:

It is a park of shady walks, of leafy bowers, of ponds, of imitation natural springs . . . Even the famous pond surrounded by a semi-circular colonnade of fluted Corinthian columns, partly broken, partly missing, is so overgrown with vines that it looks as though it had been standing there for ages. In contrast to the splendid formal gardens one sees in Paris, there is absolutely no order in the Parc Monceau: the trees are allowed to grow naturally—and by that I don’t mean unattended—the walks curve around in the most unexpected manner, and all over the park the lawn areas seem to be littered with remnants of broken Roman columns, archways, parts of ancient ruins, forgotten statuary, and what not. And yet, all this seeming naturalness is not the naturalness of neglect . . . but the studied arrangement of care and good taste.

This is a fantastical place. It is a romance of a park. But it is useless to Newman. For whom, then, does James mention the park? Well, for you and for me and for himself, so that we might be reminded that we are co-conspirators in a romance and that we are allowing ourselves to be beguiled by the romancer. He includes it to say to the careful reader, the fully engaged reader, something like the last line in the website description, but applied to the story that we are reading: “This seeming naturalness is not the naturalness of neglect but the studied arrangement of care and good taste.”

I found the description of Parc Monceau on the “Monuments in Paris” website (http://www.monument-paris.com/parc-monceau.htm) in 2007, but the link now leads only to a “Not Found” notice. EK

I PROMISED that I would return to the final sentence in the passage that has poor Newman standing in front of the convent, and I also promised that I would return to those images of New York at the turn of the twentieth century and the question of whether they, in the terms that James used to describe realism, depict experiences that are entirely controlled by our sense of the way things happen.

The final sentence about Newman’s perception of the convent that Claire de Cintré has entered was this:

It was too strange and too mocking to be real; it was like a page torn out of a romance, with no context in his own experience.

A romancer is always in danger of letting his romance get away from him. Beguiled by his own subtle drugs, he may let the rope loose, and not quite realize what he’s done until he finds himself and his romance headed for cloud cuckoo land, leaving the readers behind, with no context in their own experience that will make the romance a reality for them.

The corrective impulse is toward verisimilitude, and the techniques for achieving it are those of documentary, the methods of the documentarian. That brings me to photography, because it brought James to photography.

From 1907 to 1909, Charles Scribner’s Sons republished nearly all of James’s novels in the so-called New York Edition. For that edition, James made a selection from his entire oeuvre, made revisions to the texts, and wrote prefaces to the novels. He also commissioned a highly respected photographer, Alvin Langdon Coburn, to take photographs to be used as frontispieces to the several volumes in the edition.

Claude Rivet had told them of the projected edition de luxe of one of the writers of our day—the rarest of the novelists—who, long neglected by the multitudinous vulgar and dearly prized by the attentive (need I mention Philip Vincent?) had had the happy fortune of seeing, late in life, the dawn and then the full light of a higher criticism—an estimate in which, on the part of the public, there was something really of expiation. The edition in question, planned by a publisher of taste, was practically an act of high reparation; the wood-cuts with which it was to be enriched were the homage of English art to one of the most independent representatives of English letters.

The unnamed narrator in Henry James’s “The Real Thing”

Now why would James want to add photographs as frontispieces to the New York Edition of his novels? Before I answer that question, I’d like to consider the work of Bertram W. Beath.

Bertram W. Beath is a highly respected food critic and somewhat-less-highly-respected photographer who uses the techniques of realism in the service of romance. He sometimes signs his work “B. W. Beath” and sometimes “BWB.” Here is a quick introduction to his work from Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia in which one sometimes also finds techniques of realism used in the service of romance:

Some of Beath’s photographs have been characterized as one-frame cinematic productions. Beath distinguishes between unstaged “documentary” pictures, like his “Bronx River,” and “cinematographic” pictures, like his “Those Who Wait,” produced using a combination of actors, sets, and special effects . . .

Below are examples of Beath’s documentary photographs (“Track 3” and “Bronx River”) and cinematographic photographs (“Those Who Wait” and “Hay Bales”). Making the documentary photographs was largely a matter of being in the right place at the right time, but making the cinematographic photographs required much more effort. “Those Who Wait,” for example, required continual cellphone contact with the actors posing on the footbridge, who had to adjust their poses in response to Beath’s oral instructions. The composition in “Hay Bales” was the result of hours of manipulation of the bales by farm machinery hired for the occasion. After each “draft” of the composition, all the machinery had to be driven from the field, out of sight, so that Beath could judge the effect of the arrangement of the bales, and then the machinery had to be brought back to adjust the arrangement until Beath was satisfied.

Beath’s cinematographic photograph “Taking Their Ease” is reproduced below this paragraph. Its obvious allusions to Georges Seurat’s “Un Dimanche Après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte” and Claude Monet’s “Le Parc Monceau” are the result of painstaking calculation, color-conscious costuming, and precise manipulation of the actors. Days of preparation and advance planning were followed by hours of placing and posing the actors on the day of shooting. Many, many preliminary “draft” photographs preceded this final version. A staff of more than fifty is invisible beyond the edges of the image.

In an interview from 1998 quoted on the website of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Beath said this about the relationship between his cinematographic work and the kind of street photography that we saw in the images of New York made in James’s era:

From my earliest attempts at restaurant criticism I saw and understood the element of theater in dining, but my understanding that there could be an element of theater in photography came only after quite a long time and quite a large number of photographs. I had been focused on recording something. Increasingly, I began to focus on making something. The documentary motive never completely disappeared, but the motive to transform what I had formerly intended only to document began to dominate. I think I am heading now toward a balance of the two, a balance that is reaching its apotheosis in my series Water.

The result, the seeming naturalness of Beath’s cinematographic photographs, is not really the naturalness of documentary photography, but the studied arrangement of elements in the artist’s projected world, as we will hear Henry James say shortly.

MADELINE AND I didn’t get around to seeing The Museum of Modern Art’s blockbuster exhibit of B. W. Beath’s enormous cinematographic photographs until nearly the end of its run, but when we did see it, it gave me the theme and title for this essay.

I don’t want you to think that I was just standing there looking at Beath’s “Taking Their Ease,” say, and the whole thing came to me in a flash. No. It simmered for some time, and didn’t reach its full flavor until a Sunday several weeks after the exhibit had closed, the day when, as I mentioned at the start of this essay, Madeline and I were strolling through Central Park. We stopped at the Tavern on the Green to have a pastis at the outdoor bar. As we were leaving, Madeline detoured to the ladies’ room. Passing through the little crowd of people outside the restaurant waiting for taxis and shuttle buses, I heard someone ask, “Did you see the B. W. Beath photographs at MoMA?”

I looked in the direction of what I’d heard, and I saw a young man and a young woman conversing. The man had asked the question, and the woman answered it.

“Yes,” she said. “Yes, I did.”

“What did you think of them?” asked the man. “I’m curious.”

“Well, technically, I thought they were brilliant.”

“In what sense?”

“Very well focused. Sharp. Highly detailed. Technically advanced.”

“And the content?”

“Banal. Totally banal. But that’s why they capture modern life so brilliantly. Because modern life is totally banal. They are really slices of modern life.”

“Really,” he said, with a note of surprise in his voice.

“And the patience!” she said. “He must sit for hours and hours, just waiting for the right moment. Or maybe it’s luck. No, it’s patience, not luck. He’s like a nature photographer, but he’s observing people. People in their habitat.”

Slowly, gently, the man said, “It’s artifice.”

“Artifice?” she asked.

“Those photographs are staged. He sets them up as if he were making a movie.”

“Staged? You mean they’re fakes?”

“For each photograph, he assembles a cast, a crew, he sets the stage, manipulates the actors—”

I didn’t have a smartphone at the time, nobody did, but I always carried my camera with me. I always had it in my pocket. Because I realized what an opportunity Chance had given me, I had already taken it from my pocket and turned it on, so I was ready. It was at that moment that I took their picture.

Immediately after I took the picture, the young woman said, with a distant, disturbed, disappointed look in her eyes:

“But they seem so realistic.”

“Well, Cindy Sherman does the same sort of thing.”

“But she winks at you a little bit when she does it. You can tell what she’s up to. You’re in on the joke. But this B. W. Beath—I feel cheated now. I feel duped.”

“Don’t take it too hard.”

“He set me up to believe what I was seeing, to accept it for what it seemed to be: real life. But it wasn’t. It was something else. It was—”

At that point, I couldn’t help myself.

“It was romance,” I said.

The man turned toward me and said, “What?”

I said, “Sorry. I couldn’t help overhearing. You were talking about B. W. Beath. I think he uses the techniques of realism in the service of romance.”

“Who the hell asked you?” said the young woman.

At that point I made a conciliatory gesture, Madeline arrived, and we retreated into the park.

THE YOUNG WOMAN’S REACTION is poignant testimony to the fact that too great a degree of verisimilitude, too thoroughgoing an application of the techniques of realism, may do a disservice to a romance. It may beguile the readers so completely that they forget that the romance is a romance, and that is not quite what the romancer wants, I think.

I think that the romancer wants the relationship with the reader or other audience to remain cooperative; he does not want to dupe the reader or viewer entirely; he wants to solicit and earn the willing suspension of disbelief, but not to hoodwink the reader into unquestioning acceptance.

James for his part seems to have worried that the effect of Alvin Langdon Coburn’s photographic illustrations might be to create too great a degree of verisimilitude. In fact, he seems to have begun worrying about that possibility almost from the moment he commissioned the photographs.

He imposed stringent limits on them to ensure that they did not lean too far in inspiring a belief that the novel that followed the frontispiece presented things as they happened. According to remarks that Coburn made years later, after the New York Edition had been published with the photographs,

James did not want the kind of realistic description that [photographer J. J.] Pennell offered. Instead of actual places and objects James required types and archetypes. The illustrator had to recognize in nature and society what already existed in the author’s mind and make an ideal representation of it.

[J. J. Pennell made an exhaustive documentary photographic record of Junction City, Kansas, at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. (See James R. Shortridge’s Our Town on the Plains: J. J. Pennell’s Photographs of Junction City, Kansas, 1893-1922, published by the University Press of Kansas in 2000.)]

After the commitment had been made and the photographs were set to appear as frontispiece illustrations, James wrote about his concerns, at length, in the preface to the first volume. Among many other things, he had this to say:

Nothing . . . could more have amused the author than the opportunity of a hunt for a series of reproducible subjects . . . small pictures of our “set” stage with the actors left out; and what was above all interesting was that they were first to be constituted.

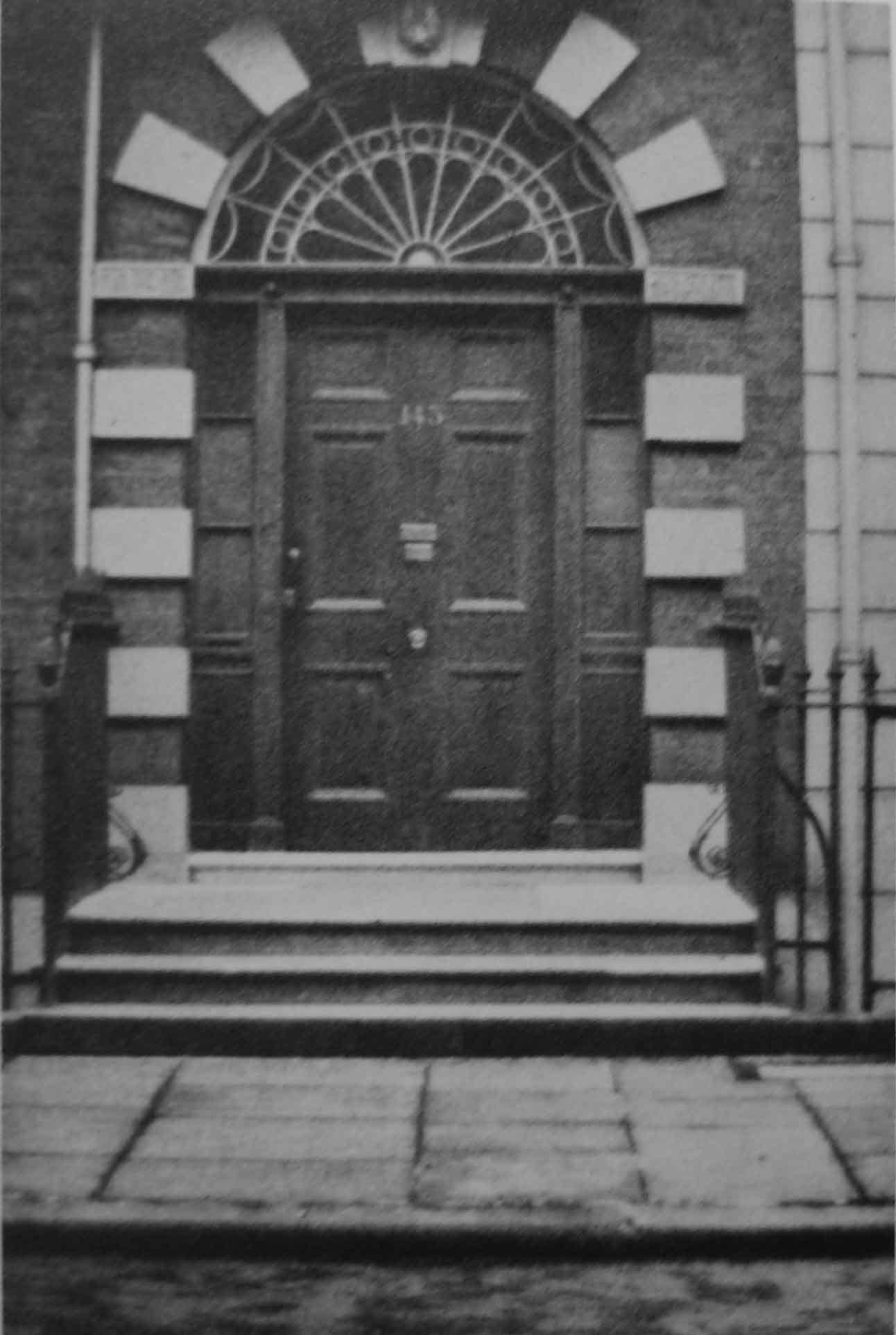

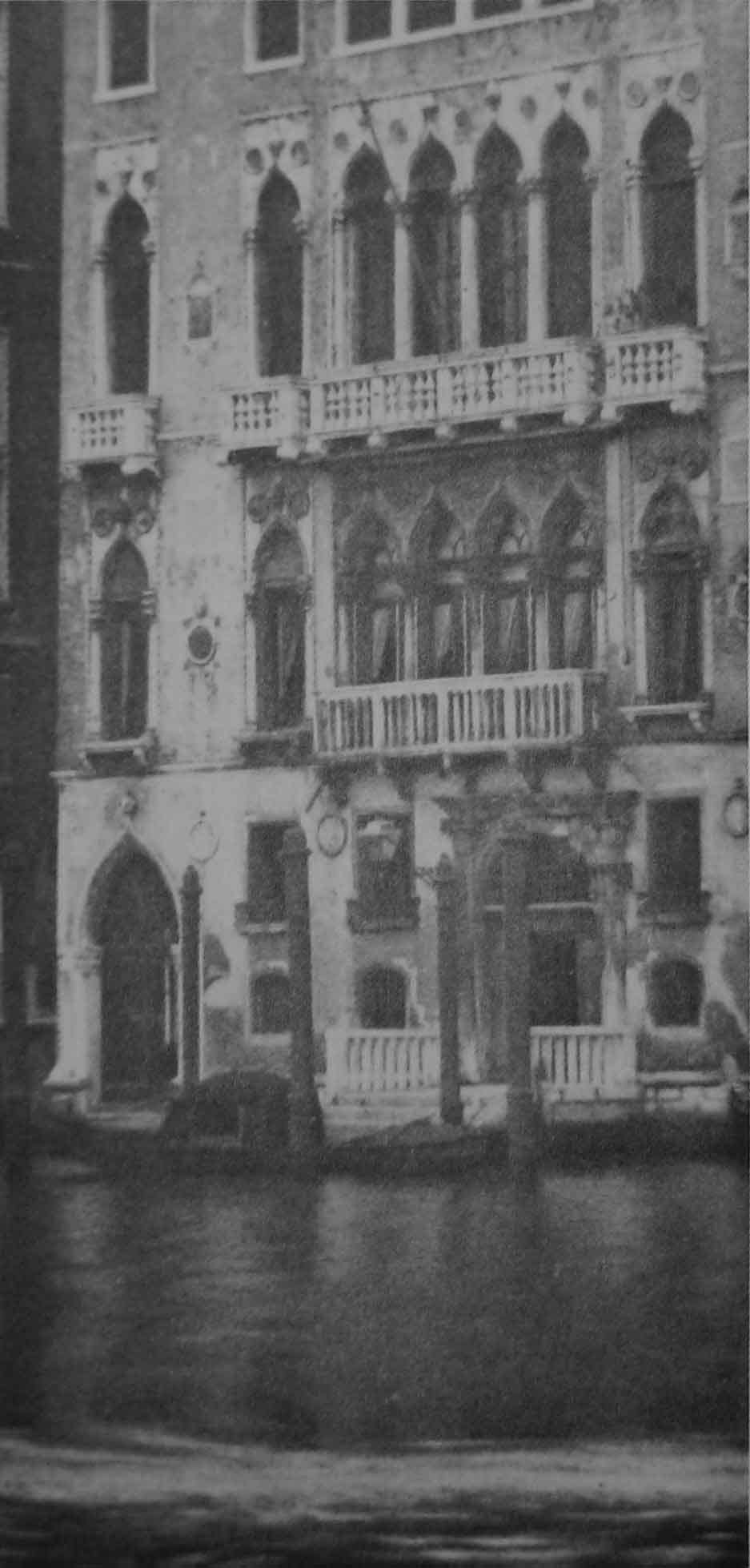

So James and Coburn set out wandering the streets of London and Paris and Venice in search of suitable subjects for these frontispieces. Below are six of them.

“The Curiosity Shop” especially interests me, and it seems to have been the one that most interested James, too, for he singled it out as an example of a successful search. In the preface, he wrote:

On the question, for instance, of the proper preliminary compliment to the first volume of “The Golden Bowl” we easily felt that nothing would so serve as a view of the small shop in which the Bowl is first encountered.

The problem thus was thrilling, for though the small shop was but a shop of the mind, of the author’s projected world, . . . our need . . . prescribed a concrete, independent, vivid instance, the instance that should oblige us by the marvel of an accidental rightness. . . . It would have to be in the first place what London and chance and an extreme improbability should have made it, and then it would have to let us truthfully read into it the Prince’s and Charlotte’s and the Princess’s visits.

This must have been a remarkable ramble. Here we have James—who acknowledges that the shop he conjured for The Golden Bowl had risen up and away from experience to become a shop of the mind, lifted from the real world and lofted into the author’s projected world, a romance of a shop in a romance of a tale—setting out with Coburn in tow to find a real shop that could play the part of the imaginary one.

It was Quixotic behavior. No, it was beyond Quixotic. It was as if Don Quixote had himself written the romances that so beguiled him and then set off to live what he came to believe was the reality of them. Its contemporary equivalent would be B. W. Beath’s beginning to believe that all of his “cinematographic” photographs were “documentary” photographs and then beginning to reminisce about the great good fortune that had allowed him to come upon such telling moments in the random chaos of everyday life.

Obviously, we can tell from the picture of the curiosity shop that appeared as the frontispiece that James and Coburn did find a shop that could play the part. Where did they find it? James refused to say. All he said in the preface was this:

It of course on these terms long evaded us, but . . . as London ends by giving one absolutely everything one asks, so it awaited us somewhere. It awaited us in fact—but I check myself; nothing, I find now, would induce me to say where.

Well, of course not.

Saying where the shop could be found would have done what James had worried that a photograph might do. It would have driven a stake in the ground at a specific spot in London and tethered The Golden Bowl tightly to it. Employing the techniques of realism with such a heavy hand, encumbering the story with such a palpable reference to the world of things as they happen, would have been using realism to fetter the balloon of romance so snugly that it could never rise and drift, and that no artful romancer would allow himself to do.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Professor Francisco Collado-Rodríguez of the University of Zaragoza for inviting me to deliver to his graduate students in American literature a lecture on realism in the work of Henry James. Without that invitation, I doubt that I would have been thinking about realism and Henry James when Madeline and I were strolling through Central Park.

I am also indebted to Elizabeth Nagengast and Dossie McCraw, the actors who played the young couple discussing the work of B. W. Beath.

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading the Personal History at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future episode by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.