FOR ALL OF HIS ADULT LIFE, Eric Kraft has been working to construct a single large work of fiction, The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. (That is not to say that he has been working on it all the time throughout all of his adult life, although his wife, Madeline, who insisted that he stop driving after finding once too often that the green light he seemed to see at an intersection was shining in another world, might contend that such a characterization would be accurate. We mean merely that he has worked on it for some time nearly every day from the age of eighteen onward, if we count thinking as working.) The Personal History is composed of many smaller parts interconnected in intricate ways, like a complex machine or a multi-celled organism or a human society or a bowl of clam chowder.

The Babbington Review: We’re back. I’m here with Eric Kraft, author of the voluminous work of fiction he calls The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. Welcome back.

Eric Kraft: It’s a pleasure to be here—again.

TBR: Actually, I was welcoming our readers, but you’re welcome, too. Of course.

EK: Well, ah, thank you.

TBR: Let’s recap briefly. In our earlier interview, you offered a well-rehearsed origin story for the Personal History, and I did my best on behalf of the Review and our readers to pry you from the practiced version—

EK: [chuckles] Yes, you did.

TBR: And I think I succeeded—to a degree. Let’s see if I can loosen you up a bit more this time. Ready?

EK: Ready. I think.

TBR: You “met” Peter Leroy while daydreaming over a German lesson. At some point you began writing about him. Tell me about that—the first experience of writing about this character.

EK: I began writing about Peter Leroy in an exploratory way, not for publication, and not even in an attempt to tell a story, just to find out what was there. This exploratory phase—which I think of as practice now—lasted nearly eighteen years, eighteen years spent learning about Peter’s friends, the town of Babbington where he lived, his family, his experiences, his feelings and ideas, scenes, snatches of conversation, encounters, bits and pieces—

TBR: I’m hearing something practiced again.

EK: Sorry. As I told you last time, I have said these things before. I’ve been asked these questions before, and my answers don’t vary much. I’ll try to improvise a little more.

TBR: Tell me: do you have any of that material—the stuff you call practice?

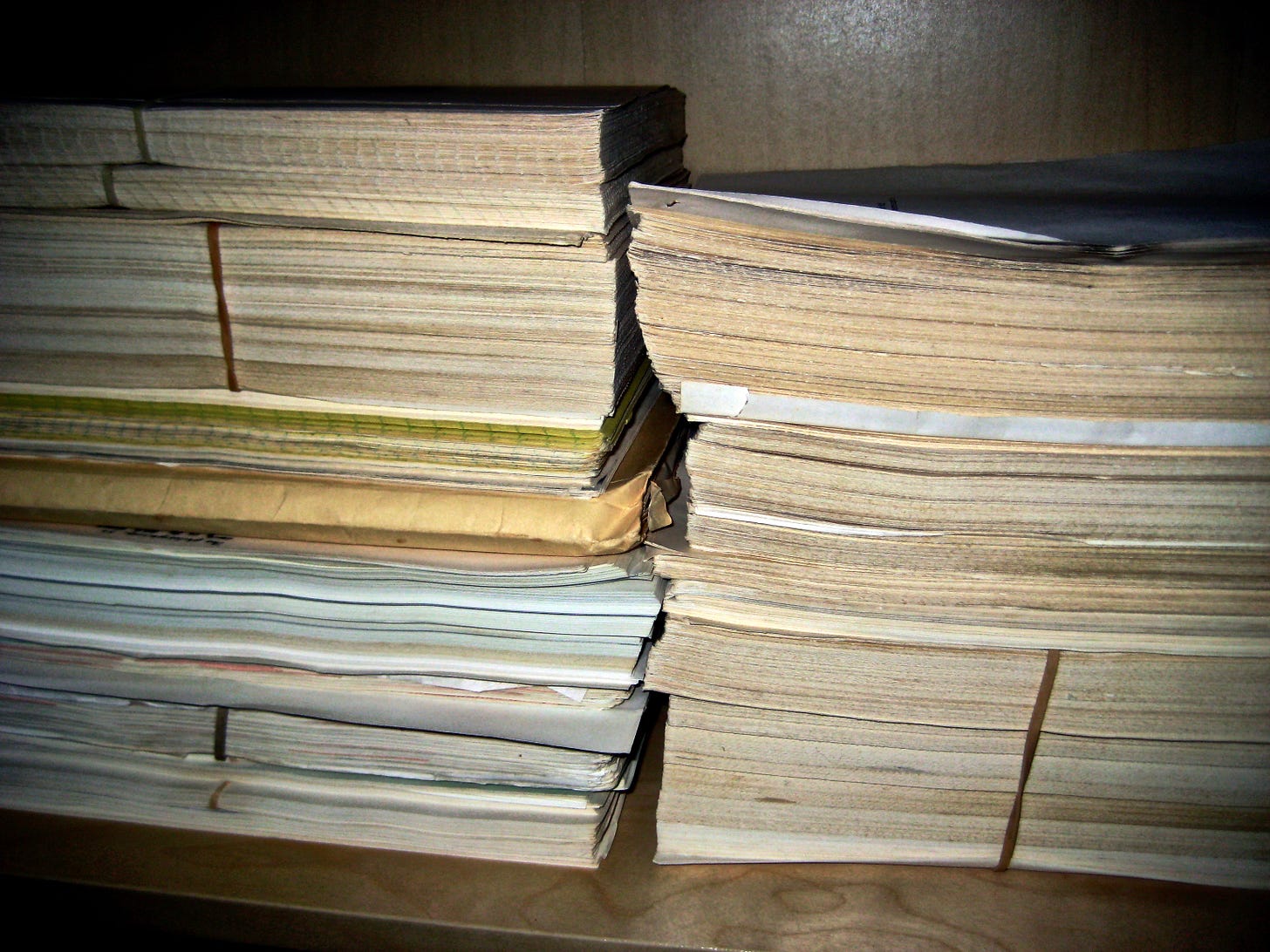

EK: Yes. I do. Stacks of it.

TBR: Would you ever make it public?

EK: No.

TBR: Would you give it to a library or university?

EK: No.

TBR: Why not?

EK: I don’t want my mistakes made public. I want the finished work to be all there is. No scraps, nothing that should have been thrown away but wasn’t.

TBR: Okay, I guess I understand that.

EK: Some day I have to get around to actually throwing all the scraps and mistakes away.

TBR: Ah! The fact that you haven’t done that suggests to me that you don’t actually want to do that. You do want someone to see the scraps and mistakes.

EK: Moving right along—

TBR: Ha. All right. Go ahead.

EK: While I was practicing, I didn’t think that I was practicing. I thought I was writing a novel—a novel about Peter Leroy. But whatever it was or was to become, I couldn’t stop working on it.

TBR: Was that all you were working on at the time? I mean—did you have a day job?

EK: Oh, yes. I always have. At the time that we’re talking about I had left teaching and become an editor at an educational publishing company.

TBR: Care to say what one?

EK: Ginn and Company, in Boston.

TBR: A company with a long history before you joined it.

EK: Yes. I think—

TBR: Founded in 1867 by Edwin Ginn, originally called Ginn Brothers, specializing in school texts from very early in its history.

EK: You’ve certainly done your homework!

TBR: I’m just reading from my phone.

EK: Oh. Of course.

TBR: So you became an editor at Ginn—

EK: Yes, and I worked in educational publishing for the next seven years, from 1968 through—or nearly through—1975.

TBR: I detect a little foreshadowing in there.

EK: You’re right. Be patient.

TBR: Patience isn’t really one of my virtues, but go on, and I’ll wait im-patiently to find out what happened in 1975.

EK: So—during that time, in the evening or early morning hours, I continued elaborating Peter Leroy and his world, creating his personal history, adventures, and experiences. The only person who experienced it was Madeline. She heard it. That was the beginning of a lifetime habit. She’s always been the first audience—the first auditor.

TBR: First auditor. I like that.

EK: So do I.

TBR: So—the work grew—for an audience of one—and you accumulated “stacks of it.”

EK: Right—and as it grew I began to ask myself—more and more often—what I was going to do with all of the stuff I’d written.

TBR: Oh, come on. You must have intended to publish it eventually—or at least hoped to.

EK: That’s not quite what I’m talking about. Well, maybe it is—partly. I mean that I was—overwhelmed by it—and confused by it. It had grown so large that I couldn’t—grasp it. I couldn’t even imagine a form that would contain it all. The bits and pieces were piling up, and my ideas were accumulating even faster. I could see that the longer I waited to begin publishing this work, the less likely it seemed that I would ever get it into a form in which it could be published—or even find a form that could accommodate it all.

TBR: Whew.

EK: The hunt for form was wearying and frustrating. It almost killed the work.

TBR: Really? Or are you just being dramatic?

EK: I’m being honest. I couldn’t “get my head around it.” When I tried to make something coherent out of what I’d done, I’d begin on one tack, go a little way, decide that it was wrong, change course, try again, change again, and so on. It wasn’t actually giving me headaches, but if I’d been prone to headaches it wouldhave given me headaches.

TBR: When was this?

EK: Roughly 1970 to 1975.

TBR: Wow. Five years. Five years struggling to find the form for the thing?

EK: Yes. And during those five years there were times when I wanted to quit, forget about Peter Leroy, do something else.

TBR: How did that feel?

EK: Oh, sometimes I felt that I wasn’t up to the task, and sometimes I wasn’t sure that the task was worth doing, and sometimes I just felt—I don’t know—defeated by my own undertaking.

TBR: But you kept writing it—accumulating more and more of it?

EK: Yes. Even though it was frustrating me, at times even annoying me, I kept writing bits and pieces of—it—whatever it might be—if it ever became anything at all.

TBR: And throughout this time the First Auditor was the only audience for it?

EK: Yes. [pauses, knits his brows]

TBR: Anything wrong?

EK: I’m deciding whether to tell you something—show you something.

TBR: Take your time.

EK: [grins] Sometime in the mid-nineteen-seventies, I wrote something called “The Evolution of the Half-Time Show.”

TBR: What was that like?

EK: It was a bunch of very short passages strung together, just brief episodes involving a couple of characters—

TBR: Did it take place in Babbington?

EK: Yes.

TBR: During Peter’s childhood?

EK: No. During his teenage years. His late teens, I think. If I’m remembering it correctly—

TBR: [snorts]

EK: That sounded like a snort of doubt.

TBR: It was. I suspect that your claiming not to remember “The Evolution of the Half-Time Show” adequately is a cover-up.

EK: You think that I remember it perfectly well but I’d like to hide it in a fog of forgetfulness?

TBR: I do.

EK: Well, I remember that Ariane was in it. I mean, I think I remember that Ariane was in it.

TBR: And Albertine?

EK: No.

TBR: Really?

EK: If I remember correctly.

TBR: [snorts]

EK: One thing I remember very well is that I read it to Madeline.

TBR: Of course. The First Auditor.

EK: Right.

TBR: Where was this? Set the stage for me.

EK: We were living in Stow, Massachusetts, in a small house that had a tiny front porch. I read it to her there, while we were sitting in a couple of chairs that friends had given us and we’d and repainted yellow.

TBR: How did she react to it? What did she think of it?

EK: You can judge for yourself.

TBR: I can? How?

EK: I photographed her while I read. I had bought an East German camera, a Hanimex Praktica, used, and I had it at my side, on a tripod, with a cable shutter-release.

TBR: And you have the pictures?

EK: [grins] I do. Here they are. [produces a small stack of photographs, face down]

TBR: Wow.

EK: I’ll show them to you in order. Here we go. [turns the top photograph over, like a card]

TBR: She looks attentive, even eager.

EK: That might be because I’m handing her a margarita. [turns the next card]

TBR: Here she looks puzzled.

EK: The narrative—well—it was a fragmented piece of work.

TBR: Fragmented?

EK: Right—as if it had once been whole but had been shattered.

TBR: Into fragments.

EK: Right.

TBR: Resulting in something that might puzzle any audience.

[EK turns another photo.]

TBR: Ah!

EK: I’ve made her laugh. This may mark the arrival of humor in The Personal History. I’m not quite sure how it happened. I don’t know whether I actually wrote something that was funny or whether I added something in the reading—some text or maybe just an attitude.

TBR: An attitude?

EK: An attitude toward the work, my work, an attitude toward the author of the work, me. [turns a photo]

TBR: You’ve really got her now.

EK: By now, the time of this photo, I had turned a corner. Before, I worked very hard at being someone I was not. The work that I produced was deliberately difficult. It was very, very serious—and it was very, very dull. I think it was also annoying—and pompous—and bloated. In this reading, I improvised, and I turned away from that set of attitudes and turned toward the ridiculous. I turned away from what Emerson called “the painful kingdom of time and place” and toward what he called “immortal hilarity.”

TBR: May I see the last card—the last photo? [EK turns the last photo.] Ah! I see her looking toward the future—envisioning a future in which you will bring her more hilarity.

EK: Hm. Maybe. I hope you’re right.

TBR: [Clears his throat.] Well.

EK: Well.

Do we show the public . . . the mechanism behind our effects? . . . Do we display all the rags, the paint, the pulleys, the chains, the alterations, the scribbled-over proof sheets—in short, all the horrors that make up the sanctuary of art?

Charles Baudelaire, quoted by Walter Benjamin in The Arcades Project

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading the Personal History at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future episode by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.