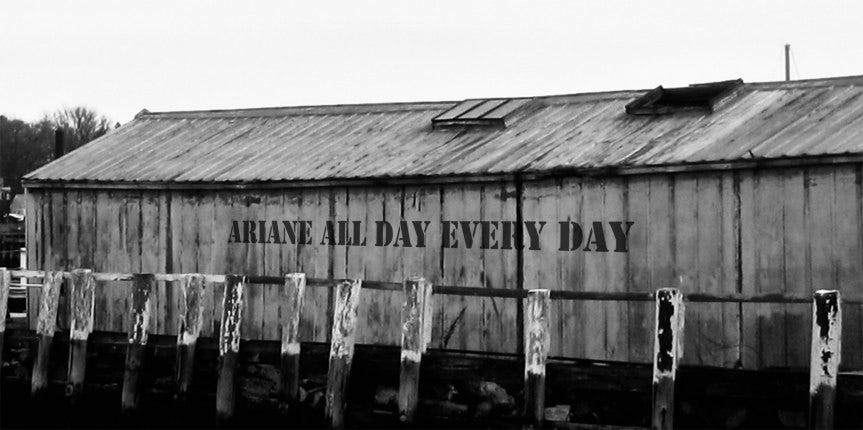

Ariane Lodkochnikov was for several years of her life what would now be called a performance artist, or perhaps she’d be called an improv actress, but she would have rejected that, because in the early years she claimed that she wasn’t acting. I think she was being honest about not acting, in those early years. She didn’t “act” then, in the sense that she didn’t play a part. She was just being herself. Her theater was an abandoned warehouse on the estuarial stretch of the Bolotomy River. She was onstage, all day, every day, for years, but being onstage was all she was doing, just being, just living. Her life was the show. Actually, in those early years, only part of her life was the show: the part that her audience could see and hear. What went on in her mind she kept to herself—until she decided to remake herself, onstage, out loud, in full view, while she cooked.

I was in the audience as often as I could be, and sometimes I was even on stage, a part of the show. (Hers was never strictly a one-woman show. Her onstage home had a door—a back door—and sometimes someone would walk to that door, knock, and be welcomed onstage, into the show, into her life, her performance, at least for a while.)

Whether I was in the audience or onstage, I took notes. I had a small notebook, small enough to fit in my pocket. I’d been carrying a notebook for years, since the days when I was the scribe of a boys’ club called The Young Tars. I was furtive about my note-taking at first, because I assumed that she wouldn’t want me to take notes. Why did I assume that? I don’t know for sure, but maybe it was just because experience had taught me that most of the things I wanted to do were wrong, or would be regarded as wrong. Taking notes about other people was one of those things. It’s surprising how many people don’t want you taking notes about what they’re doing. At least it surprised me—back then.

For a while I thought that Ariane didn’t notice my taking notes, but in time I came to realize that she did notice. I’d see it in a certain look, a certain grin, or a wink, or she’d pause in what she was saying, and her pause would give me a chance to catch up with what she’d said or done, but I was slow to understand that she might be pausing specifically to allow me to catch up.

Her acting—rather than her simply being onstage, on view—began with her cooking.

At first, she wasn’t much of a cook. She’d be the first to admit that. In fact, she wasthe first to admit that. I remember when it happened.

She was cooking something. What? Let me check my notes. Here it is: clam chowder. Of course.

She was working at the task, saying nothing, just working at making the chowder—but then she stopped suddenly. She looked at what she’d been doing. She looked at her hands. She looked at the audience. She looked at me. “I’m not doing this well,” she said. “I’m not even trying to do it well. I don’t even know why I’m doing it at all. I mean, why cook? What’s the point of it? Why don’t we—I mean why don’t I—just eat things that I can eat without cooking them? Okay, I understand that some things are not good to eat without cooking—like raw meat. I know some people eat it. It’s even supposed to be a delicacy. But not for me. No thank you. But many of the things that I’m putting into this chowder I would eat raw. Many of them I do eat raw. Carrots. Celery. Tomatoes. Clams. I can’t say that I really like raw clams—but I’ve eaten them.”

A long pause. She looked at the clams. She picked one up.

“Clams. Wow. Clams were a big part of my childhood. They were very important in my family. My father supported us by digging clams.”

Another long pause. She shook her head.

“You know that old saying that the shoemaker’s children have no shoes? People used to say that. I guess it was supposed to mean that the shoemaker was so busy making other people’s shoes that he had no time to make shoes for his own family. Maybe. Or maybe it meant that shoemakers didn’t make enough money to support their families—so the kids had no shoes—so the moral would have been “Get a better job than shoemaking.” Well, that didn’t apply to clamdigging. The clamdigger’s children had plenty, let me tell you. Not shoes. Not money, either. But clams. Oh, yeah, plenty of clams. Whenever my father couldn’t sell all the clams he’d dug, or when he couldn’t get a decent price for them, we got them. We didn’t get the good ones, of course. Those brought the best prices, so we never saw them. We got the big old tough ones. The chowder clams.”

Another pause. Another shake of the head. A little snort.

“The things my mother did with those tough old clams. Wow. She’d chop them up so you didn’t have to chew your way through their toughness. She did the chewing for you by chopping them. The chopped clams went into all kinds of things—baked stuffed clams, clam sauce for spaghetti, clam fritters, even clam hash.”

Another pause.

“My mother was always making something to eat. ‘What are you doing, Ma?’ ‘I’m making breakfast—I’m making lunch—I’m making dinner.’”

Another pause. A wrinkled brow.

“You know, when people are cooking, they claim that they’re making something. ‘I’m making clam hash,’ or ‘I’m making dinner,’ but that’s not true. They’re not making anything. Look at what I’ve got here. I didn’t make any of it. The clams, the carrots, all of that, it’s already made—and not by me. All I’m doing is—what?—I’m just changing it. I’m changing this bunch of stuff into dinner—into chowder.”

She threw her hands up. “Hey, I need a dictionary up here.”

The next day she had three. One was from me, the other two from other admirers.

“I was wrong,” she said. “Cooking is making something.” She held up the stack of dictionaries. “Turns out make means many things. One of these dictionaries has eighty-four definitions. The first one is ‘to bring into existence by shaping or changing material, combining parts, etc., as in make a dress or make a work of art.’ What does cooking make? Anybody want to risk a guess?” She flicked her glance around the few people in the audience. She stopped at me. “Peter?”

“A meal?”

“Yeah, it could a meal—that’s true—but let’s just say it makes a dish—even if it doesn’t make a whole meal. So it brings something into existence—a dish—by shaping or changing material—ingredients—combining parts—more ingredients—et cetera—more ingredients—as in make a baked stuffed clam or make a clam chowder.”

She turned solemn. “I like people who admit it when they’re wrong,” she said. “I was wrong. Cooking makes something. It makes raw ingredients into something better—a dish. It transforms raw ingredients into something better—a delicious dish.”

She grinned and she batted her eyes in exaggerated flirtation. “Pretty good, huh?” she asked. “You thought I was just a dumb broad up here—but I’ve got ideas—or I’m starting to get ideas—and here’s another one. Acting is like cooking. It transforms someone into someone else—raw ingredients into a delicious dish. I think I’m going to start acting. I think I’ve already started acting. Did you get all that, Peter?”

I nodded confidently and held my notebook up for her to see.

In truth, I hadn’t gotten all of it, but I’d gotten the gist of it, and I’d gotten some words and phrases. I felt pretty sure that I could make something out of what I had.

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies and Herb ’n’ Lorna.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.