It Means Something

Margot and Martha Glynn

In the days when our father, the painter Andrew Glynn, was most productive and most widely known, many people who ought to have known better took as an axiom the notion that paintings of the kind that he made, abstractions, did not mean anything, need not mean anything, and should not mean anything. Like a poem, the thinking went (if thinking played a part in it), a painting should not mean, but be. That was not at all what our father thought.

“Everything in the work means something,” Father said. “The choice of materials means something. The placement of elements within the work means something. Even the decision to make the work means something, and everything that happens during the making of it means something. When it’s finished, it may not mean more than a fleeting feeling, a burst of emotion, a hackneyed idea, or a state of mind inexpressible any other way but this way, the way the artist has presented it, but still it means something.”

Sweet autumn clematis (Clematis paniculata or Clematis terniflora) grew on the fence that ran along the narrow road beside our house.

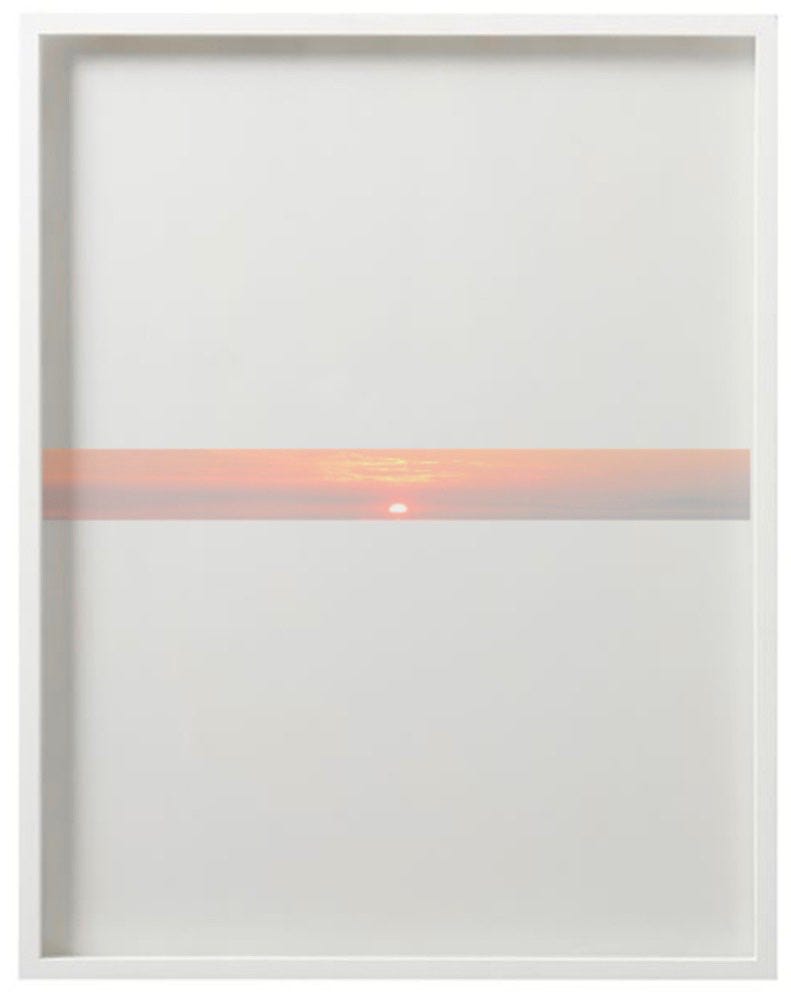

I see in the Glynns’ work an ongoing investigation of what—as I’ve pointed out elsewhere (“The Prince of Starkness,” NYRCC, August 1973)—Nelson Dredge (aka “Gobi”) has simplistically termed aleatory inevitability, the notion that, given time enough, the great god Chance will see to it that everything that can happen does happen. In Gobi’s hands, the concept is jejune and essentially meaningless, but the Glynns find in it a push-me-pull-me dynamic that creates a tantalizing ambiguity in their work. Gobi totters like a toddler on the shoulders of the same towering figure on whose shoulders the Glynn Twins stand steadily: the artist Andrew Glynn, their father. Consider the paintings of Gobi’s “white period,” of which Dawn, Montauk, is characteristic. In each of the white-period paintings, the ostensible subject of the painting is confined to a slice of the center of the work, rendered almost photographically, but faded or diluted to diminish its significance, implying, heavy-handedly, that the actual subject of the painting is the work’s relationship to what lies beyond that slice of the familiar, the illimitable vastness where anything that can happen does happen. In other words, everything but its announced subject. Get it? (Nudge-nudge.)

Derek Beemer, “Stuff Happens,” New York Review of Contemporary Culture, February 9, 1974

Derek Beemer wouldn’t recognize aleatory inevitability if it jumped up and bit him on the ass, which it will do, someday.

Gobi, letter to the editor, New York Review of Contemporary Culture, February 23, 1974

The Babbington Review is an occasional publication of the Babbington Press.

The Babbington Press and all its Publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.