The beautiful Miranda and I were sitting in a restaurant’s temporary shed in Manhattan, on a street that I will not name, one evening a couple of years into the coronavirus pandemic. The evening was cold. We were wearing layers of sweaters under heavy coats. We had arrived wearing surgical masks, but we had removed the masks when we were seated at our table. All the other diners had removed their masks as well. We had martinis in front of us, each straight up, with a twist of lemon.

We raised our glasses and clinked them.

“To you, my darling,” said I.

“No, to you, my darling,” said Miranda.

We regarded our frigid drinks.

A moment passed.

“Shall we risk it?” asked Miranda.

“I’ll go first,” said I, gallantly.

I sipped. I lowered my glass. I smiled.

“It didn’t freeze to my lips,” I said.

“I noticed,” said Miranda. “Here goes.”

She sipped. “Ah,” she said. “I needed that. We’ve been confined to quarters for far too long. Cocktails at home. Dinner at home.”

I was about to agree, but a big man at a table separated from ours by one empty table encircled by yellow plastic tape of the crime-scene type to ensure that it stayed empty to enforce prudential distancing, said something that made me remain silent. Instead of speaking, I raised my eyebrows in the way that Miranda and I do to say, “Listen: someone is saying something that might be interesting.”

Miranda returned the signal with a wink.

Together, we listened.

“I know what you’re going to say,” said the big man. “You’re going to tell me that the pandemic has killed people. You’re going to tell me that it has orphaned little children. You’re going to tell me that it has cost people their jobs. Yeah, yeah, yeah, I know all that, but I’m telling you the pandemic has hurt me worse than anybody else. Much worse. Why? You want to know why? I’ll tell you why. Because it has fucked the only really brilliant idea I ever had in my life. That’s why.”

I raised both eyebrows. The big man’s companions leaned toward him, possibly to indicate sympathy.

“What was it?” asked one of the members of the big man’s party. “What was the only really brilliant idea you’ve ever had in your life?”

There was, unmistakably, a note of mockery in the question.

“Mock me if you want,” said the big man, “but it was a brilliant idea. When it came to me I realized that it was literally a defining moment. I never thought I’d have one of those. But I did. Life-changing. Literally. That one moment. That one idea.”

“The suspense is killing me,” I muttered.

Miranda raised a finger to her lips. She didn’t quite say, “Shhh.”

“Well? What was it?” demanded another member of the big man’s party, apparently also in danger of being killed by the suspense.

“It was an idea for a restaurant. A restaurant with a theme.”

“A gimmick, you mean?”

“Okay. A gimmick.”

“And the gimmick was—?”

The big man took a swallow of his drink, displaying a certain talent for timing.

“The gimmick was masks,” he said, shaking his head.

“Masks!” cried his crew, as one.

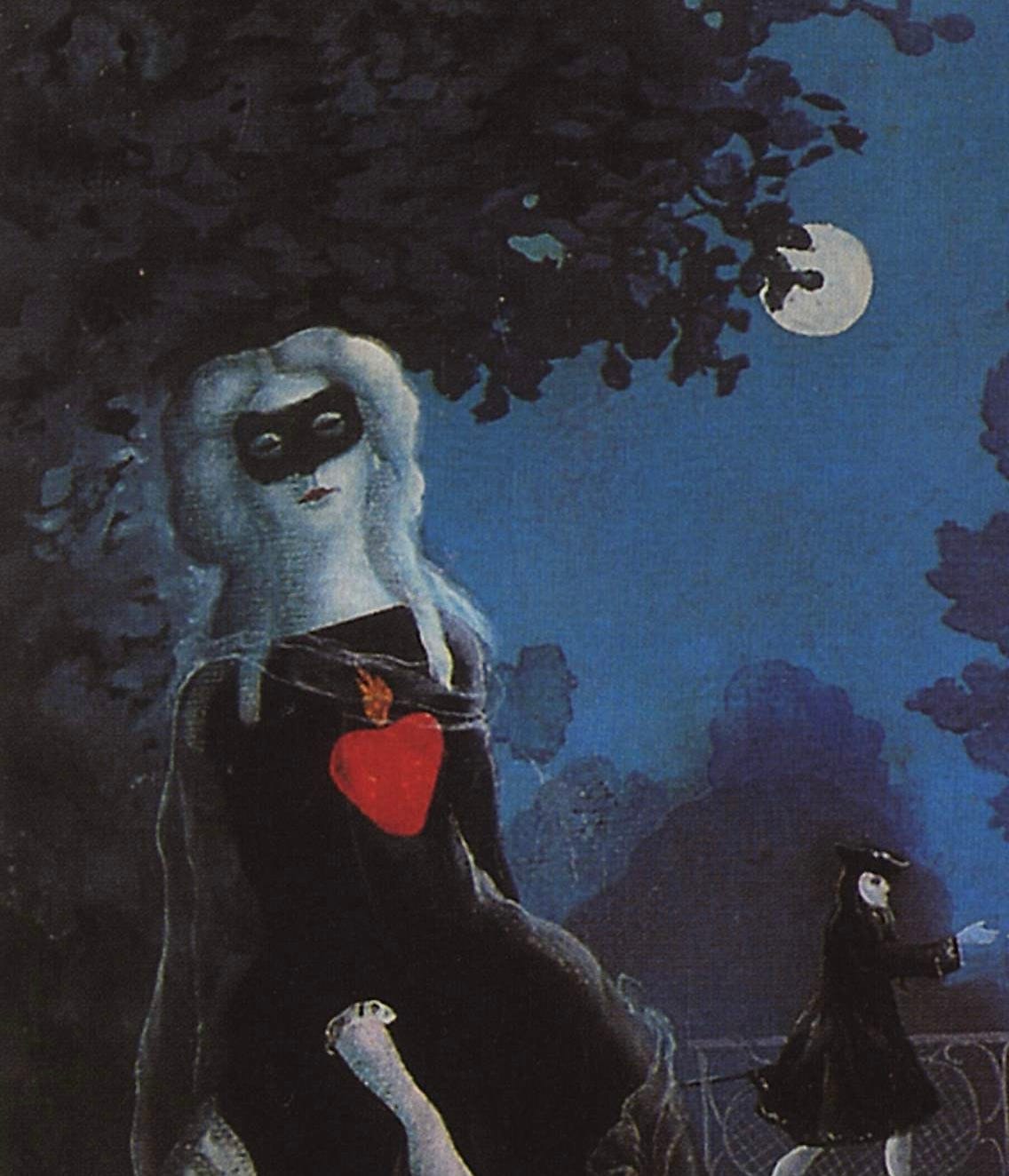

“Yeah, masks. Not masks like please-virus-don’t-kill-me masks. Masks like a masked ball. Masks that suggest an evening of mystery, romance, flirtation, maybe a hint of danger—but mysterious-stranger danger, not germ danger. Anyway, I had this idea, a restaurant with masks, and I got so I was obsessing about it—like it wouldn’t leave me alone. I started fiddling around with logos for the place—ads for it—menus—signature cocktails—and somewhere along the line I realized that I had to commit myself to this. I realized it was—don’t laugh—my destiny.”

He paused, dramatically, took a swallow of his drink, and chuckled. “I was going to call the place The Masquerade until it came to me that the name of the restaurant should be ‘Masquerade,’ not ‘The Masquerade.’”

“If he adds, ‘Get it?’ I can’t be held responsible for my actions,” I said, still muttering.

“Get it?” asked the big man.

“Ah!” said his listeners, as one. “Like ‘Facebook,’ not ‘The Facebook,’ said one of their number, just to make it clear that they actually did get it, or that at least that he did.

“If it had a theme song, it would be ‘Life is a masquerade, old chum,’ like ‘Life is a cabaret, old chum.’ Good, right?”

There were murmurs of assent from the others at the large man’s table. Someone said something that might have been, “Brilliant.”

“Did someone actually say, ‘Brilliant’? asked Miranda, whispering.

I took a long look at the group at the large man’s table. “I suppose it’s possible,” I said, with one of those shrugs that means “the stupidity of humankind never fails to amaze me.”

One member of the large man’s group began singing, softly, “‘I’m afraid the masquerade is over—’”

“Brilliant,” I said.

“Yeah, well,” growled the big man, “What I want to know is, ‘Why me?’ What have the gods got against me? You know what I’m saying? Why do I have to spend most of every day shaking my fist at the heavens and asking, ‘Why me, Lord?’ It’s like this pandemic is a personal attack on me and my hopes and dreams. It’s like a thundering voice from above telling me, ‘You’re overreaching. You’re too ambitious. We’re gonna smack you down, boy.’”

“Millions have suffered,” said a still, small voice.

Without moving our heads, Miranda and I scanned the large man’s table to see which of his companions had the temerity to interject this hint that the gods might not have limited their wrath to the big man alone.

We saw the people at the table glancing at one another in the same way.

“Millions have died,” said the same still, small voice.

It didn’t come from the big man’s table. It came from a waitress who was circling the table, delivering another round of drinks.

Miranda and I exchanged a glance. Miranda made the thumbs-up sign.

The big man seemed about to say something to the waitress. His face reddened, and he drew a deep breath. The woman beside him put her hand on his arm. “Let it go,” she said.

The big man just sat and fumed for a moment. Then he called out to the waitress, “We all suffer! We all suffer one way or another! I’ve suffered! And I don’t deserve to suffer!”

Heads turned throughout the room.

“And we all die, too, by the way!” growled the big man.

“Stan,” said the woman beside him, giving his arm a squeeze.

The waitress who pointed out that millions have suffered and millions have died stood silent after she finished delivering the drinks.

“She’s struggling to repress her disgust,” whispered Miranda, leaning across the table to ensure that I heard her.

“Yes,” I said, also whispering, “she is.”

Then there came another still, small voice. “‘No man is an island,’” it said.

Heads turned, swiveled, looking for the source of this second still, small voice. It came from one of Big Man Stan’s companions.

“I don’t need this,” growled Stan. “It’s bad enough the gods and the viruses are against me. I don’t need to have my so-called friends turn against me, too. I’m out of here.”

He rose from the table, threw his napkin onto his plate, shrugged off an attempt to hold him back, and stormed out of the restaurant.

A stunned silence.

Miranda mouthed “Who’s going to pay the check?”

I chuckled.

Audibly, one of the members of Stan’s group asked, “Who’s going to pay the check?”

I burst out laughing. Miranda tried to muffle her laughter with her napkin.

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Praise of Folly (1509):

If anyone tries to take the masks off the actors when they’re playing a scene on the stage and show their true, natural faces to the audience, he’ll certainly spoil the whole play and deserve to be stoned and thrown out of the theatre for a maniac. . . . It’s all a sort of pretense, but it’s the only way to act out this farce.

Magnus Eisengrim in Robertson Davies’s World of Wonders:

All theatres of that sort‚the proscenium theatres that are out of favor with modern architects‚ took their form and style from the ball-rooms of great palaces, which were the theatres of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Gilbert, in Oscar Wilde’s “The Critic as Artist”:

“The difference between objective and subjective work is one of external form merely. It is accidental, not essential. All artistic creation is absolutely subjective. The very landscape that Corot looked at was, as he said himself, but a mood of his own mind; and those great figures of Greek or English drama that seem to us to possess an actual existence of their own, apart from the poets who shaped and fashioned them, are, in their ultimate analysis, simply the poets themselves, not as they thought they were, but as they thought they were not; and by such thinking came in strange manner, though but for a moment, really so to be. For out of ourselves we can never pass, nor can there be in creation what in the creator was not. . . . Yes, the objective form is the most subjective in matter. Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

John Donne, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, “Meditation XVII”

No man is an island entire of itself;

every man is a piece of the continent,

a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

as well as if a promontory were,

as well as any manner of thy friends or of thine own were;

any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

it tolls for thee.

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies and Herb ’n’ Lorna.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.