WHENEVER ANYONE TEACHES skills that he or she has acquired “the hard way,” I seem to hear a confessional note. It’s as if an old illusionist, a sleight-of-hand artist, a pickpocket, a thief, a master cracker of safes, or an old seducer, sensing that the light is growing dim, decides to tell all, so that the tricks of the trade will be appreciated at last, once and for all, forever.

Well—I may have some tricks that I can pass along to you, but I can’t guarantee that they will work—for you. I can only tell you what has worked for me—and that’s what I’m going to do.

IF YOU WANT to write your memoirs the way I am writing mine, you must have some stories that you want to tell. I hope that you will want to tell them honestly—but artfully. You ought not to feel that you have to stick too closely to the facts, but what you say should seem plausible within its own context. You should use your memories, but you should make them new, review them, revisit them, rethink them, revise them, and revivify them, working on them enough so that you’re forced to find the essence of them. You should weave a light elastic web of contextual links that suspends your stories in thin air but anchors them to reality. You should roam the whole range of your thoughts and emotions, from the ridiculous to the sublime. You should regard yourself with irony, but you must not become a slave to irony. You should remind yourself, over and over as you work, that a serious thought need not wear a serious face, nor a joke require a wink and a nudge. You must not be afraid of sentiment, but you must not wallow in it or lure the reader into wallowing in it. You must learn to live in the past for long periods of the present. You must be exacting in your craftsmanship. You must be prepared to get lost in the work and to enjoy wandering there. You should probably follow the advice given on the packages of powerful medications: do not operate heavy machinery while wandering in the work. Because you’ll have your past in your mind all the time, even when you think you’re not at work, it’s best to leave the driving to someone else.

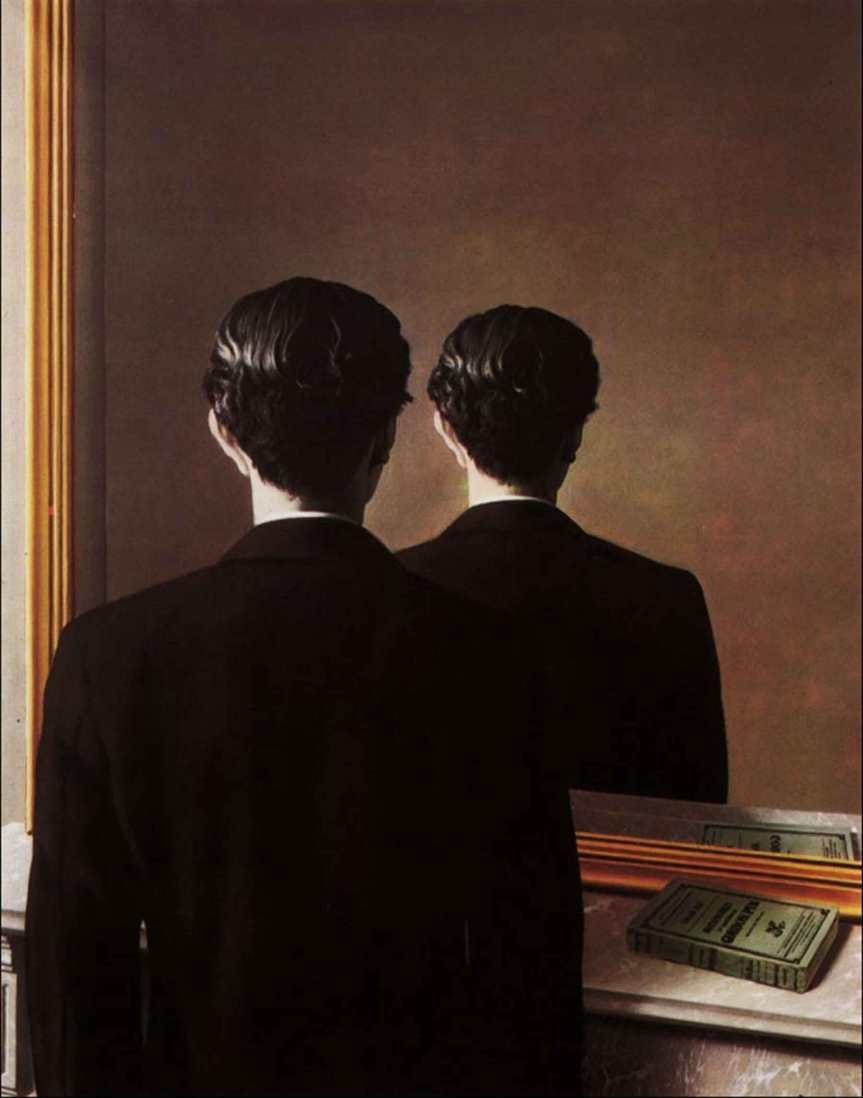

To accomplish all of that, I suggest that you create someone who will do the job better than you could do it yourself.

Here’s the idea:

In Midnight Oil, V. S. Pritchett wrote: “A writer is, at the very least, two persons. He is the prosing man at his desk and a sort of valet who dogs him and does the living. There is a time when he is all valet looking for a master, i.e., the writer he is hopefully pursuing.”

I think that every writer achieves this separation to some degree, creating an alter ego who does the writing, and I think that those who do it most successfully find that the writing self leads them to discoveries they would not have made on their own.

In the course of this workshop I’ll put you through some exercises that may reveal restrictions you’re putting on your writing self and help you liberate your writing self and send that self off to new adventures and discoveries.

Why should you do what I’m suggesting? Why create another self to do your writing when you already have a perfectly good self who does the living?

Here’s my answer to that question: another self is a means to a better understanding of the truth, the essence, the heart of what you have to say and to a more honest and complete expression of it. Let me explain why “you” are probably avoiding that honesty and completeness, perhaps without even being aware that you are.

You may be censoring yourself for reasons of self-image, self-protection, self-promotion, greed, generosity, ambition, pleasure, taste, the pursuit of “a higher truth,” compassion, tact, fear, or—well, you get the idea.

Here’s William Butler Yeats on the subject of the author and the author’s other, in “A General Introduction for My Work”; he says, “A poet writes always of his personal life, in his finest work out of its tragedy, whatever it be, remorse, lost love, or mere loneliness; he never speaks directly as to someone at the breakfast table, there is always a phantasmagoria. Dante and Milton had mythologies, Shakespeare the characters of English history or romance; even when the poet seems most himself, when he is Raleigh and gives potentates the lie, or Shelley ‘a nerve o’er which do creep the else unfelt oppressions of this earth,’ or Byron when ‘the soul wears out the breast’ as ‘the sword outwears its sheath,’ he is never the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast; he has been reborn as an idea, something intended, complete. . . . He is part of his own phantasmagoria.”

Here’s Marcel Proust in Contre Sainte-Beuve, as translated by Sylvia Townsend Warner: “Sainte-Beuve’s great work does not go very deep. The celebrated method which, according to Paul Bourget and so many others, made him the peerless master of nineteenth-century criticism, this system which consists of not separating the man and his work . . . ignores what a very slight degree of self-acquaintance teaches us: that a book is the product of a different self from the self we manifest in our habits, in our social life, in our vices. If we would try to understand that particular self, it is by searching our own bosoms, and trying to reconstruct it there, that we may arrive at it. Nothing can exempt us from this pilgrimage of the heart.”

Now I want to tell you a story. It’s not mine. It’s “The Private Life,” by Henry James. I’m going to give you a condensed version, but I hope you’ll read it in full. You’ll find it on the sepia-tinted handout.

As is often the case in James’s stories about writers, the story is told by an unnamed narrator who observes an exalted master from a position lower on the ladder of literary success.

In this case, the narrator is among a group of Londoners vacationing in Switzerland, after having endured what the narrator calls “the modern indignity of travel—the promiscuities and vulgarities, the station and the hotel, the gregarious patience, the struggle for a scrappy attention, the reduction to a numbered state.”

They are staying at a “balconied inn . . . on the very neck of the sweetest pass in the Oberland . . . for a week.”

They are Lord and Lady Mellifont, Clarence (Clare) Vawdrey, whom the narrator calls “the greatest (in the opinion of many) of our literary glories,” and Blanche Adney, whom the narrator calls “the greatest (in the opinion of all) of our theatrical.”

Of Clare Vawdrey, the narrator says: “He never talked about himself; . . . He differed from other people, but never from himself . . . and he struck me as having neither moods nor sensibilities nor preferences. . . . I never found him anything but loud and liberal and cheerful, and I never heard him utter a paradox or express a shade or play with an idea.”

Of Blanche Adney, the narrator says that she “had settled it for [Clare Vawdrey] that he was going to write her a play and that the heroine, should he but do his duty, would be the part for which she had immemorially longed.”

At dinner Blanche Adney asks Vawdrey “if he really didn’t see by this time his third act.”

Vawdrey tells her that he wrote a splendid passage before dinner.

“Before dinner?” the narrator says. “Why, cher grand maître, before dinner you were holding us all spell-bound on the terrace.”

Vawdrey looks at the narrator hard, and says, “Oh, it was before that.”

“Before that you were playing billiards with me,” says Lord Mellifont.

“Then it must have been yesterday,” says Vawdrey.

“You told me this morning you did nothing yesterday,” Adney objects.

Vawdrey is rattled. “I don’t think I really know when I do things,” he says, and then he admits, “I’m afraid there is no manuscript.”

“Then you’ve not written anything?” asks the narrator.

“I’ll write it tomorrow,” Vawdrey claims.

“Ah, you trifle with us,” the narrator says.

At that, Vawdrey seems to think better of what he’s said. “If there is anything you’ll find it on my table,” he claims.

The narrator goes up to Vawdrey’s room and opens the door. He finds the room dark and is about to strike a match when he realizes to his surprise that a figure is seated at a table near one of the windows.

He retreats with a sense of intrusion; but as he does so he realizes that the figure at the desk is Vawdrey. He calls out: “Hullo, is that you, Vawdrey?”

The figure doesn’t turn to look at the narrator, nor does he answer the narrator, but the narrator is convinced that he recognizes Clare Vawdrey, whom he left a moment ago, downstairs, in conversation with Blanch Adney.

The next evening, the narrator describes to Blanche what he saw. “It looked like the author of Vawdrey’s admirable works. It looked infinitely more like him than our friend does himself,” he says.

“Do you mean it was somebody he gets to do them?”

“Yes, while he dines out and disappoints you.”

“Disappoints me?” she murmurs.

“Disappoints every one who looks in him for the genius that created the pages they adore,” says the narrator.

The following evening, Vawdrey does read a scene to Blanche, and the narrator later asks her, “Is the scene very fine?”

“Magnificent,” she says, “and he reads beautifully.”

“Almost as well as the other one writes!” says the narrator.

[For the complete version of Henry James’s “The Private Life,” see the pdf version of this issue of the Babbington Review, available at the bottom of this page.]

Let me give you one more example, a truly amazing one: Fernando Pessoa, who surely must hold the world’s record in the art of making others. He had eighty, more or less, depending on who’s counting and how fully we require an other to be developed as an individual in order to count as an other. We’re not talking about mere pseudonyms, remember. Pessoa called his others “heteronyms,” to underline the distinction, and he gave each of them a unique physical appearance, biography, literary outlook, and writing style. Here’s Pessoa describing the sudden appearance of the first few of these heteronyms, and their work: “Suddenly, . . . a new individual burst impetuously onto the scene. In one fell swoop, at the typewriter, without hesitation or correction, there appeared the ‘Triumphal Ode’ by Alvaro de Campos—the ode of that name and the man with the name he now has. I created . . . an inexistent coterie. I sorted out the influences and the relationships, listened, inside myself, to the debates and the difference in criteria, and in all of this, it seemed to me that I, the creator of it all, had the lesser presence. It seemed that it all happened independently of me. And it seems to me so still.”

Now let’s consider what might go into the making of an other. We’ll consider a hypothetical case, the case of Mark Dorset.

For very many years Mark had wanted to write a topical autobiography, to record his life and thoughts in a catalog. He never seemed to be able to find the time. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that he would never write that book. Since he knew that he would never write that book, he decided instead to find someone else to write it. The book would not be a topical autobiography. It would be a novel in the form of a topical autobiography.

Mark was astonished that it had taken him so long to realize that he needed someone else to write what he wanted to write, but once the decision had been made, he thought that he could see the many ways in which his self had been standing in the way of what he wanted to do. There were all the motives of self-aggrandizement, of course, and then there all the motives of self-defense. He had needed someone else all along.

I’m going to take you along the path that Mark traveled.

Let’s begin by examining the state of mind that impelled Mark to the discovery that he needed an other. It was characterized by a more or less constant state of annoyance that arose from his not doing the writing that he wanted to do, not making the work that he wanted to make. Then came the understanding that the excuses he gave—not enough time, too many other demands, the need to make money—were false. Well, not entirely false, of course. He really didn’t have enough time, there were too many demands on his time and energy, and he didneed to make money, but he could have found some time, at least a little time, when he could have done a little bit each day and he could have squeezed what he wanted to do in among the things that he had to do without making it impossible to do them all.

The real reason was that he didn’t think he was going to do a good job. Let’s put that more strongly: he was afraid of doing a bad job.

So. Once he had made the decision to turn the writing over to an other, all he had to do was find someone who could, and would, do the work—and do it well.

He generated some anagrams of his name. An anagram makes an excellent pseudonym, an excellent name for an other, an excellent name for a heteronym, because it allows you to demonstrate, should you ever choose to do so, that the other is you. This is what Mark got as anagrams for “Mark Dorset,” or at least what seemed useful in what he got:

Mort Drakes

Dram Stoker

Mark Strode

Drake Storm

Mr. Ad Stoker

Mr. Ado Treks

Rod Strek, M.A.

How would these people be different from Mark?

Dram Stoker might be a descendent of the author of Dracula, a moody fellow, dressed in black, subject to persecution paranoia. Why would he choose to tell Mark’s story?

Mort Drakes. His full name is Morton. He wants people to call him Mort, but most of them call him Morty. He’s a back-slapper, a salesman of some kind, secretly sick of his work. Why would he choose to tell Mark’s story?

Mark Strode might be a private eye. He might have decided to investigate Mark just to display his skill, to show how much he could uncover about even a run-of-the mill person.

Drake Storm might be an actor, or an actor-slash-waiter.

Mr. Ad Stoker might be an undertaker or a pawnbroker.

Rod Strek, M.A., would, of course, be the chair of the highly regarded MFA program at Southwest Midwest University.

These potential others began to interest Mark. He thought that he would set them a trial of some kind, an audition, to see who would get the job.

Now I’m going to put you to work, following Mark’s path. Begin by considering this: Who else might tell your story?

Make a list. List some real people. Create some people. Try some anagrams. List a couple of characters from whatever you’re currently working on.

[pause]

Now choose the four or five potential others who interest you most.

[pause]

Now jot some notes about each of those potential others as if the notes were written by each of them, in their individual voices. You might consider these notes toward a topical autobiography. Or—if you prefer, jot some notes about yourself as if the notes were written by each of the others. You might consider these notes toward a topical biography.

[pause]

Now you’re going to write a little story as one of those others.

I’m going to give you a version of the story, and I want you to write anther version that is specific to the other you choose, reflecting the other’s unique biography, literary outlook, and writing style

I’ve adapted the story from Harry Zohn’s translation of a story told by Walter Benjamin in his essay “Franz Kafka.” Here’s the story:

In a village tavern, so the story goes, the members of an informal tertullia were sitting together one autumn evening. They were all local people, with the exception of one person no one knew, a very poor, ragged man who was squatting in a dark corner at the back of the room. All sorts of things were discussed, and then it was suggested that everyone should tell what wish he would make if one were granted him. One man wanted money; another wished for a son-in-law; a third dreamed of a new carpenter’s bench; and so everyone spoke in turn. After they had finished, only the beggar in his dark corner was left. Reluctantly and hesitantly he answered the question.

“I wish I were a powerful king reigning over a big country. Then, some night while I was asleep in my palace, an enemy would invade my country, and by dawn his horsemen would penetrate to my castle and meet with no resistance. Roused from my sleep, I wouldn’t have time even to dress and I would have to flee in my shirt. Rushing over hill and dale and through forests day and night, I would finally arrive safely right here at the bench in this corner. This is my wish.”

The others exchanged uncomprehending glances.

“And what good would this wish have done you?” someone asked.

“I’d have a shirt,” was the answer.

Okay. You’re on your own. Go to it. We’ll look at your stories next time.

A note on the text: The preceding is a transcription of a recording of the first meeting of a course in memoir-writing that Peter Leroy taught at the BCAE (Babbington Center for Adult Education).

And out of what sees and hears and out

Of what one feels, who could have thought to make

So many selves, so many sensuous worlds,

As if the air, the mid-day air, was swarming

With the metaphysical changes that occur,

Merely in living as and where we live.

Wallace Stevens, “Esthétique du Mal”

so many selves(so many fiends and gods

each greedier than every)is a man

(so easily one in another hides;

yet man can,being all,escape from none) . . .

—how should a fool that calls him ‘I’ presume

to comprehend not numerable whom?

e. e. cummings

The problem of other minds is the problem of how to justify the almost universal belief that others have minds very like our own.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition)

Last name: Drakes

This unusual and interesting name has two possible origins, the first and most generally applicable being from the Old English . . . byname or nickname “Draca,” meaning “dragon” or “snake.” . . . The derivation for all these forms is from the Latin “draco,” snake, or monster. . . . The name may also be from the Middle English “drake” male of the duck. The final “s” on the name indicates the patronymic, i.e. “son of Drake.” One Awdry Drakes was christened on August 15th 1563 at St. Vedast Foster Lane and St. Michael le Querne, London.

The Internet Surname Database

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading the Personal History at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future episode by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.