Imagination; Improvisation

Mr. Beaker came to my parents’ house a few times a week to read to me and to try to teach me to read. He would run his finger along the lines of type as he read to demonstrate that it was from them that he was taking his words, and I soon began to understand that he was just repeating what was already in the book, that he wasn’t improvising the stories from the pictures, and I began to think that Mr. Beaker wasn’t as smart—as clever—as I had thought. … [W]hen he asked me to try to read, I would return to the pictures, to my memory of the story as he had read it, and to whatever popped into my head, and I would improvise. … I used the written words that I could read only as I used the pictures—as prompts for memory, spurs for imagination.

Little Follies, “The Fox and the Clam”

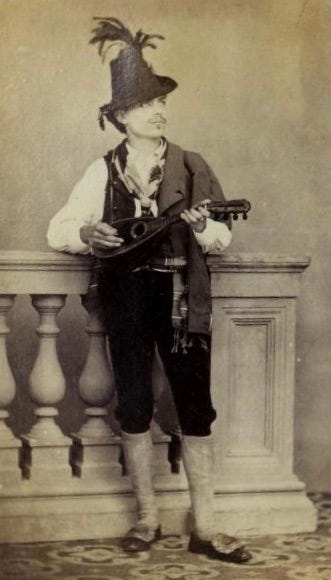

A little square-built fellow, whose whole dress consisted of a shirt, and short leather breeches, which hung loose and unbuttoned at the knees, sat with a guitar, and twanged the strings merrily. Now he sang a song, now he played, and all the peasants clapped their hands. My mother remained standing; and now I listened to a song which seized upon me quite in an extraordinary way, for it was not a song like any other which I had heard. No! he sang to us of what we saw and heard, we were ourselves in the song, and that in verse, and with melody. …

“Bravo!” said my mother, and all the peasants clapped their hands and shouted, “Bravo, Giacomo! Bravo!”

Upon the steps of the little church we discovered, in the mean time, an acquaintance—our Federigo, who stood with a pencil and sketched the whole merry moonlight piece. As we went home he and my mother joked about the brisk Improvisatore, for so I heard them call the peasant who sung so charmingly.

“Antonio,” said Federigo to me, “thou, also, should’st improvise; thou art truly, also, a little poet! Thou must learn to put thy pieces into verse.”

I now understood what a poet was; namely, one who could sing beautifully that which he saw and felt. That must, indeed, be charming, thought I, and easy, if I had but a guitar.

The first subject of my song was neither more nor less than the shop of the bacon-dealer over the way. Long ago, my fancy had already busied itself with the curious collection of his wares, which attracted in particular the eyes of strangers. Amid beautiful garlands of laurel hung the white buffalo-cheeses, like great ostrich eggs; candles, wrapped round with gold paper, represented an organ! and sausages, which were reared up like columns, sustained a Parmesan cheese, shining like yellow amber. When in an evening the whole was lighted up, and the red glass-lamps burned before the image of the Madonna in the wall among sausages and ham, it seemed to me as if I looked into an entirely magical world. The cat upon the shop-table, and the young Capuchins, who always stood so long cheapening their purchases with the signora, came also into the poem, which I pondered upon so long that I could repeat it aloud and perfectly to Federigo, and which, having won his applause, quickly spread itself over the whole house, nay even to the wife of the bacon-dealer herself, who laughed and clapped her hands, and called it a wonderful poem,—a Divina Commedia di Dante!

From this time forth everything was sung. I lived entirely in fancies and dreams …Hans Christian Anderson, The Improvisatore, translated by Mary Howitt

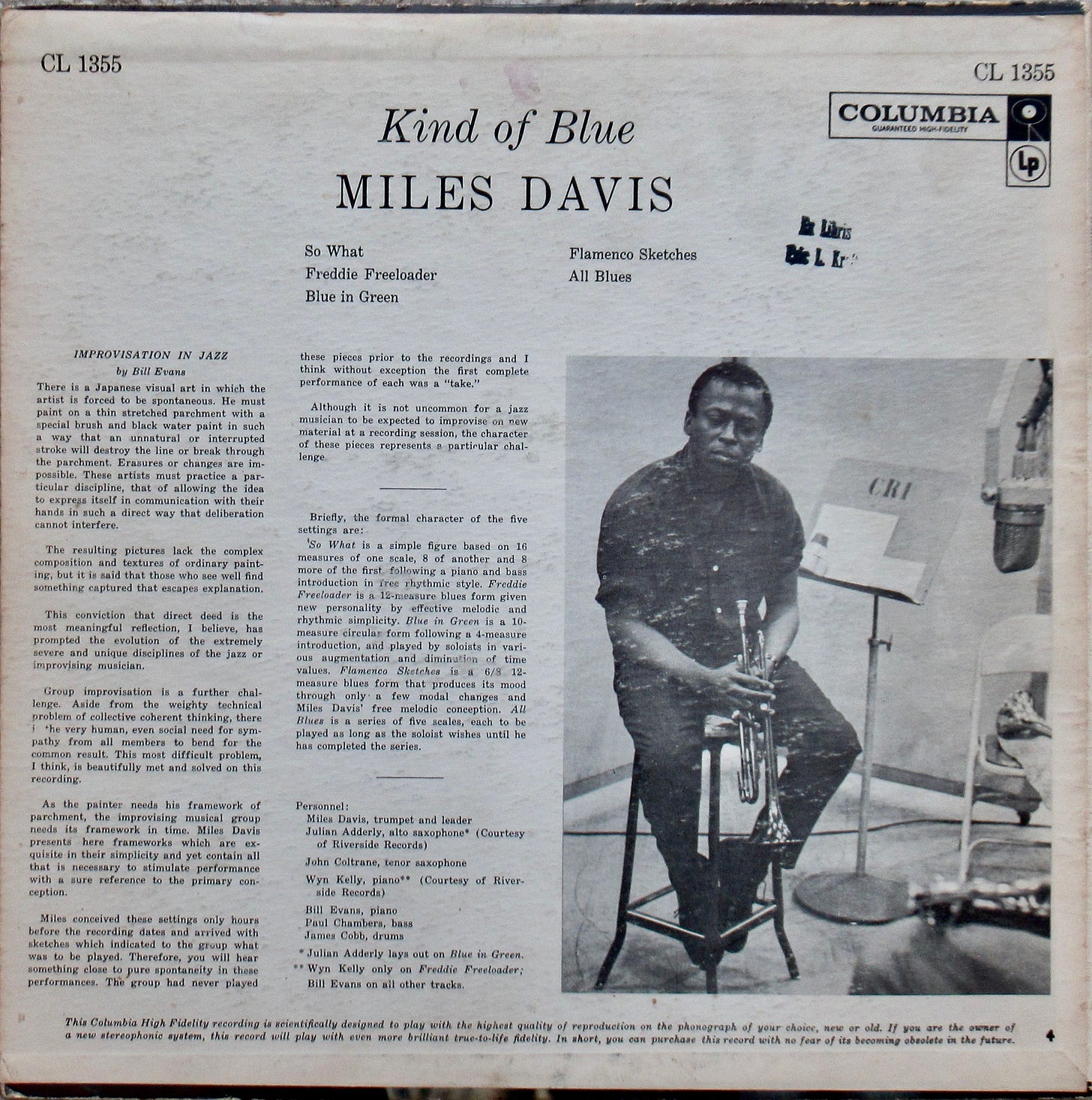

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see well find something captured that escapes explanation.

This conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflections, I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician.

Group improvisation is a further challenge. Aside from the weighty technical problem of collective coherent thinking, there is the very human, even social need for sympathy from all members to bend for the common result. This most difficult problem, I think, is beautifully met and solved on this recording. …

Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings and I think without exception the first complete performance of each was a “take.”Bill Evans “Improvisation in Jazz” (the liner notes to Kind of Blue)

Notes for The Topical Autobiography of Mark Dorset:

If I had but a guitar: If I had the time, if I had the temerity, if I had the ego, I would have written the topical autobiography, I would be writing it now, instead of this note. “If I had” could be a topic.

Miles Davis and Kind of Blue: I could have posted the back cover of my copy of Kind of Blue above and no one would have noticed the difference—well, no one but me and Kraft. My admiration for Miles (might as well make that veneration) began in high school. After a while, I think I wanted to become Miles. On several occasions I traveled from Babbington to Greenwich Village to buy clothes at Paul Sargent Ltd. because I had read (in Down Beat, I think) that Miles bought his suits there. I bought a gray single-button double breasted suit there that was much, much cooler than I was.

Improvisation: It’s what I’m doing, Reader. Right now. Typing these words. It’s what I’ve done for this entire page. It’s what I’ve done for 102 pages of the Topical Guide to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It ain’t easy. I’m not complaining. But it ain’t easy. Just think for a minute how much easier Kraft’s job is. All he has to do is cut and paste from work he wrote long ago. Nothing to it. Whereas I have to pick up his themes and run with them, sprinting at the sound of the starter’s pistol, with a daily deadline. Under the gun. I’m not complaining. I’m not paid, by the way. I volunteered. Well, almost. I accepted the job when I was asked if I’d “like” to do it. I just want you to know that I’m not in it for the money. If you subscribe so that you gain access to all of my Topical Guide posts, the money goes to Kraft, not to me. Even so, I wish you would subscribe. You’d be telling me that my work has value. You’d be clapping your hands and shouting, “Bravo, Improvisatore Marco!”

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” and “The Static of the Spheres,” the first four novellas in Little Follies.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.