Hope versus Despair (or Fear)

“So do you know what the moral of the story is?” I asked. I was about to say, “The moral is: ‘Never give up hope, even when you’re lost,’” but I didn’t get the chance, because Mort said at once, “Yeah, I get it,” took a deep breath, stuck his head out the window, and let out a yell that made the bus driver slam on the brakes. The sound coming out of Mort was really remarkably like the siren on a fire engine. It rose and fell, and he could keep it up for an astounding length of time. He would pause only long enough to take another breath, and then he would launch right back into it, a little louder and a little longer each time.

Little Follies, “The Fox and the Clam”

The authentic in man is outstanding, waiting, lives in fear of being frustrated, lives in hope of succeeding. Because what is possible can equally well turn into Nothing as into Being: the Possible, as that which is not fully conditional, is that which is not settled. Hence, from the outset, if man does not intervene, both fear and hope are equally appropriate when confronted with this real suspension, fear in hope, hope in fear. This is why the stoics—wise or all too passively wise men—advised that man should not settle in the vicinity of circumstances over which he has no power. But since in man active capacity particularly belongs to possibility, the display of this activity and bravery, as soon as and in so far as it takes place, tips the balance in favor of hope.

The specific remedy for an unfortunate event (and three events out of four are unfortunate) is a decision; for its effect is that, by a sudden reversal of our thoughts, it interrupts the flow of those that come from the past event and prolong its vibration, and breaks that flow with a contrary flow of contrary thoughts, come from without, from the future. But these new thoughts are most of all beneficial to us when (and this was the case with the thoughts that assailed me at this moment), from the heart of that future, it is a hope that they bring us.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, The Sweet Cheat Gone, “Grief and Oblivion”

Audacity or Pluck Overcoming Despair or Fear (or Prudence or Timidity)

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic … [including] the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917. Disaster struck this expedition when its ship, Endurance, became trapped in pack ice and was slowly crushed before the shore parties could be landed. The crew escaped by camping on the sea ice until it disintegrated, then by launching the lifeboats. …

After five harrowing days at sea, the exhausted men landed their three lifeboats at Elephant Island, 346 miles (557 km) from where the Endurance sank. …

Elephant Island was an inhospitable place, far from any shipping routes; rescue by means of chance discovery was very unlikely. Consequently, Shackleton decided to risk an open-boat journey to the 720-nautical-mile-distant South Georgia whaling stations, where he knew help was available. The strongest of the tiny 20-foot (6.1 m) lifeboats, christened James Caird after the expedition's chief sponsor, was chosen for the trip. …

The James Caird was launched on 24 April 1916; during the next fifteen days, it sailed through the waters of the southern ocean, at the mercy of the stormy seas, in constant peril of capsizing. …

[They] were able, finally, to land. … After a period of rest and recuperation, rather than risk putting to sea again to reach the whaling stations on the northern coast, Shackleton decided to attempt a land crossing of the island. … For their journey, the survivors were only equipped with boots they had pushed screws into to act as climbing boots, a carpenter’s adze, and 50 feet of rope. … Shackleton travelled 32 miles (51 km) with Worsley and Crean over extremely dangerous mountainous terrain for 36 hours to reach the whaling station at Stromness on 20 May.From Wikipedia (condensed)

Down below us was an almost precipitous slope, the nature of which we could not gauge in the darkness and the lower part of which was shrouded in impenetrable gloom. The situation looked grim enough. Fog cut off our retreat, darkness covered our advance.

After a moment or two Shackleton said, “We’ve got to take a risk. Are you game?”

Crean and I declared that anything was better than delay.

“Right,” said Shackleton; “we’ll try it.”

We resumed our advance by slowly and painfully cutting steps in the ice in a downward direction, but since it took us half an hour to get down a hundred yards, we saw that it was useless to continue in this fashion.

Shackleton then cut out a large step and sat on it. For a few moments he pondered, then he said:

“I’ve got an idea. We must go on, no matter what is below. To try to do it in this way is hopeless. We can’t cut steps down thousands of feet.”

He paused, and Crean and I both agreed with him. Then he spoke again.

“It’s a devil of a risk, but we’ve got to take it. We’ll slide.”

Slide down what was practically a precipice, in the darkness, to meet—what?

“All right,” I said aloud, perhaps not very cheerfully, and Crean echoed my words.

It seemed to me a most impossible project. The slope was well-nigh precipitous, and a rock in our path—we could never have seen it in the darkness in time to avoid it—would mean certain disaster. Still, it was the only way. We had explored all the passes; to go back was useless: moreover such a proceeding would sign and seal the death warrant not only of ourselves but of the whole of the expedition. To stay on the ridge longer meant certain death by freezing. It was useless therefore to think about personal risk. If we were killed, at least we had done everything in our power to bring help to our shipmates. Shackleton was right. Our chance was a very small one indeed, but it was up to us to take it.

We each coiled our share of the rope until it made a pad on which we could sit to make our glissade from the mountain top. We hurried as much as possible, being anxious to get through the ordeal. Shackleton sat on the large step he had carved, and I sat behind him, straddled my legs round him and clasped him round the neck. Crean did the same with me, so that we were locked together as one man. Then Shackleton kicked off.

We seemed to shoot into space. For a moment my hair fairly stood on end. Then quite suddenly I felt a glow, and knew that I was grinning! I was actually enjoying it. It was most exhilarating. We were shooting down the side of an almost precipitous mountain at nearly a mile a minute. I yelled with excitement, and found that Shackleton and Crean were yelling too. It seemed ridiculously safe. To hell with the rocks!

The sharp slope eased out slightly toward the level below, and then we knew for certain that we were safe. Little by little our speed slackened, and we finished up at the bottom in a bank of snow. We picked ourselves up and solemnly shook hands all round.

“It’s not good to do that kind of thing too often,” said Shackleton, slowly.

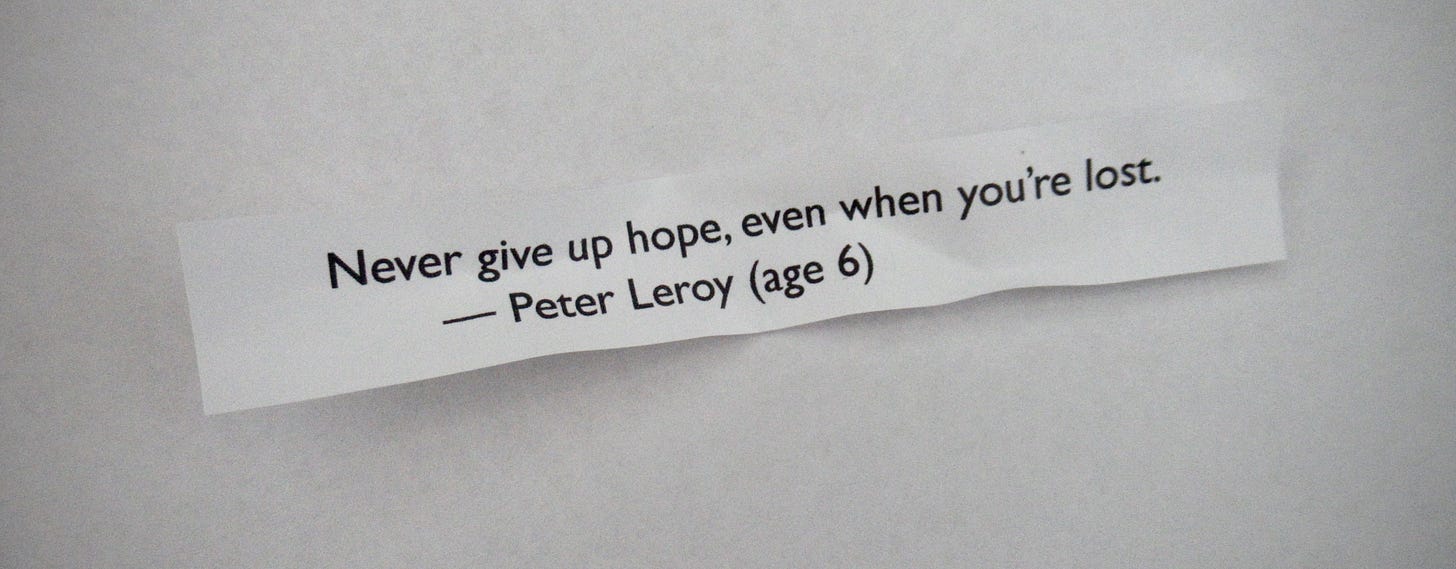

Fortune-Cookie Wisdom

[more to come on Thursday, October 14, 2021]

A note from Candi Lee Manning, my bubbly publicist:

Hi there! I’ll bet you’re asking yourself, “Why should I subscribe? I mean, like, what’s in it for me?”

Well, I’ll tell you!

By subscribing you’ll you’ll stay up-to-date. You won’t have to worry about missing anything. Every new edition of the newsletter will go directly to your inbox.

By subscribing you’ll join the crew. You’ll be part of a community of earnest screwballs who are reading the serial republication of a work that Newsweek called “great art that looks like fun,” the Seattle Times called “an ever-evolving comic masterpiece,” and the New York Times Book Review called “a weird wonder.”

Did you click that button? I hope you did! If you did, thank you!

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” and “The Static of the Spheres,” the first four novellas in Little Follies.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.