Language: Dialect, Slang, Idiolect, Shibboleths, Jargon

I ALSO ENGAGED the help of Matthew Barber. Matthew wasn’t enthusiastic at first. In fact, he was convinced that the production was going to be a farce.

“Peter,” he said, “all of you are going to look like a bunch of idiots when this hits the boards.”

“‘Hits the boards’?” I asked.

“That’s theater talk,” he said. “You’re not very familiar with the theater, are you?” he asked.

I thought of reminding him about my success as an elf, but from the way Matthew’s mouth was twisted I could tell that it wouldn’t go very far toward making him think that I was “familiar with the theater.”

“No,” I confessed.Little Follies, “The Girl with the White Fur Muff”

I did not find this theatrical use of boards in the listing of more than a thousand “definitions of theatrical terms, from Aside, Beam Angle, and Camlock, to Upstaging, VU Meter, and Wagon,” posted by the American Association of Community Theatre.

Nor did I find the use of boards to mean “stage” in “30 Words and Phrases From Victorian Theatrical Slang,” by Paul Anthony Jones (Mental Floss September 3, 2015; updated October 17, 2019), though I did find many amusing terms there, such as “CHARLES HIS FRIEND: A nickname for any uninspiring part in a play whose only purpose is to give the main protagonist someone to talk to. The term apparently derives from a genuine list of the characters in a now long-forgotten drama, in which the lead’s companion was listed simply as ‘Charles: his friend.’”

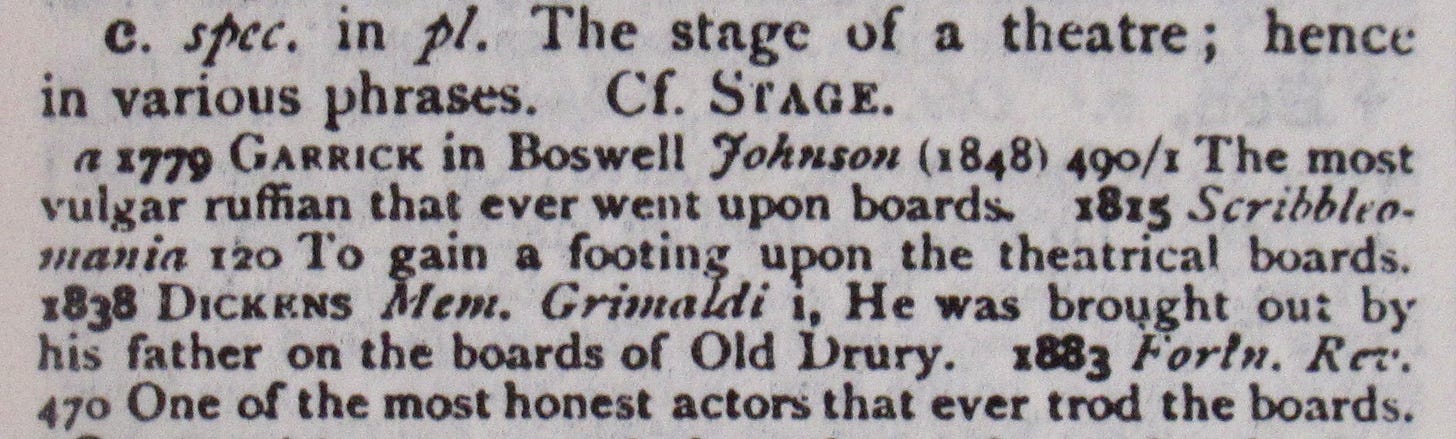

However, I did find it where I should have looked first:

Literature: Interpretation of

He shook his head and let out a long sigh. … “Look, Peter,” he said, looking me in the face and putting his hands on my shoulders, “it’s not going to be easy, you know. You can’t just have a bunch of kids running around the stage like madmen and fools. This is a very complicated play.”

Little Follies, “The Girl with the White Fur Muff”

For example:

The fascination with death and the sensationalizing of suicide are prevalent metaphysical themes which traverse all Shakespearean tragedy. These brooding themes, despite their ubiquitous portrayal, take on an idiosyncratic ethical meaning in King Lear.

“The Psyscholinguistic Semiotics and Metanormative Ethics of Suicide and Death in Shakespeare’s King Lear,” by Conner R. Hayes, in Inquiries

King Lear holds “the mirror up to nature” by reflecting the essential need for hsiao in society, as the sine qua non of civilized coexistence both within the family and within the state.

“Meaning as Merging: The Hermeneutics of Reinterpreting King Lear in the Light of the Hsiao-ching,” by Sandra Wawrytko, in Philosophy East and West

By rewriting King Lear in 1987, the Women’s Theatre Group (WTG) challenged the ideology of the New Right in Britain, which was characterized by an appeal to an allegedly idyllic past and the promotion of free market economics, individualism, and patriarchialism.

“Lear’s Daughters, Adaptation, and the Calculation of Worth,” by Stephannie S. Gearhart, in Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation

See also: Dialect, Slang, Idiolect, Shibboleths TG 11

[more to come on Tuesday, November 23, 2021]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” and “The Fox and the Clam,” the first five novellas in Little Follies.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.