Young People: Their Revolt Against Institutions, Their Readiness for Everything that Is Heroic, for Martyrdom or Crime, Their Fiery Earnestness, Their Instability

Life Lessons

When I had first tried saluting, what I saw in the mirror disappointed me, even after an hour of practice, even though I could deliver a crisp salute that seemed to me nearly as good as those I saw delivered by drill teams in the parades for Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, the Clam Fest, and Labor Day. I was disappointed because my salute was nearly as good as theirs, but not as good. I wasn’t sure why my salute fell short of the drill-team ideal, but I could see that it did.

When I tried the salute on my parents and asked them what was wrong, they were no help at all. My father beamed at the sight of me in my uniform, saluting. “Smart!” he said. “Very smart. You’ve got just the right snap there, Peter.” …

We looked at each other for a moment.

“It’s okay,” he said, and raised his newspaper.

I went upstairs, saluted in front of the mirror, and went to work, modifying the salute until I was happier with it. In the process, I learned three new lessons.

First, I learned that no one close to me, certainly not my parents, could give me an honest appraisal of anything I did.

Second, I learned that by sufficiently deviating from the norm, one can hide the shortcomings of what one does, for a time, by claiming to be working in a new area entirely. As an immediate consequence of this lesson, I developed a Tars salute, a salute sui generis, a salute outside the standards by which a drill team’s salute would be judged.

Third, I learned that if I got away with the Tars salute, if I was capable of hiding the deficiencies in what I did by appearing to be doing something outside conventional forms, outside conventional criticism, then the real truth of the matter was that no one could give me an honest appraisal of anything I did but myself.Little Follies, “The Young Tars”

The mockery of the young, their revolt against institutions, their readiness for everything that is heroic, for martyrdom or crime, their fiery earnestness, their instability—all this means nothing more than their struggle to escape that “something” that does to people what flypaper does to a fly. Basically, these struggles merely indicate that nothing a young person does is done from an unequivocal inner necessity, even though they behave as if whatever they are intent upon at the moment must be done, and without delay. Someone comes up with a splendid new gesture, an outward or inward—how shall we translate it?—vital pose? A form into which inner meaning streams like helium into a balloon? An expression of impression? A technique of being? It can be a new mustache or a new idea. It is playacting, but like all playacting it tries to say something, of course—and like the sparrows off the rooftops when someone scatters crumbs on the ground, young souls instantly pounce on it. Imagine, if you will, what it is to have a heavy world weighing on tongue, hands, and eyes, a chilled moon of earth, houses, mores, pictures, and books, and inside nothing but an unstable, shifting mist; what a joy it must be whenever someone brings out a slogan in which one thinks one can recognize oneself. What is more natural than that every person of intense feeling get hold of this new form before the common run of people does? It offers that moment of self-realization, of balance between inner and outer, between being crushed and exploding.

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities, “Pseudoreality Prevails” (translated by Sophie Wilkins)

We ask ourselves, “Why does one chess player play better than another?” The answer is not that the one who plays better makes fewer mistakes, because in a fundamental way the one who plays better makes more mistakes, by which I mean more imaginative mistakes. He sees more ridiculous alternatives. If any of you play chess you may have sat in front of the board with a published diagram and then refused to look at the next move, saying, “Well, what crazy thing did he do now?” The mark of the great player is exactly that he thinks of something which by all known norms of the game is an error. His choice does not conform to the way in which, if you want to put it most brutally, a machine would play the game.

Therefore, we must accept the fact that all the imaginative inventions are to some extent errors with respect to the norm. Nothing is worth doing which is not this mad maverick kind of change. But these errors have the peculiar quality of being able to sustain themselves, of being able to reproduce themselves.

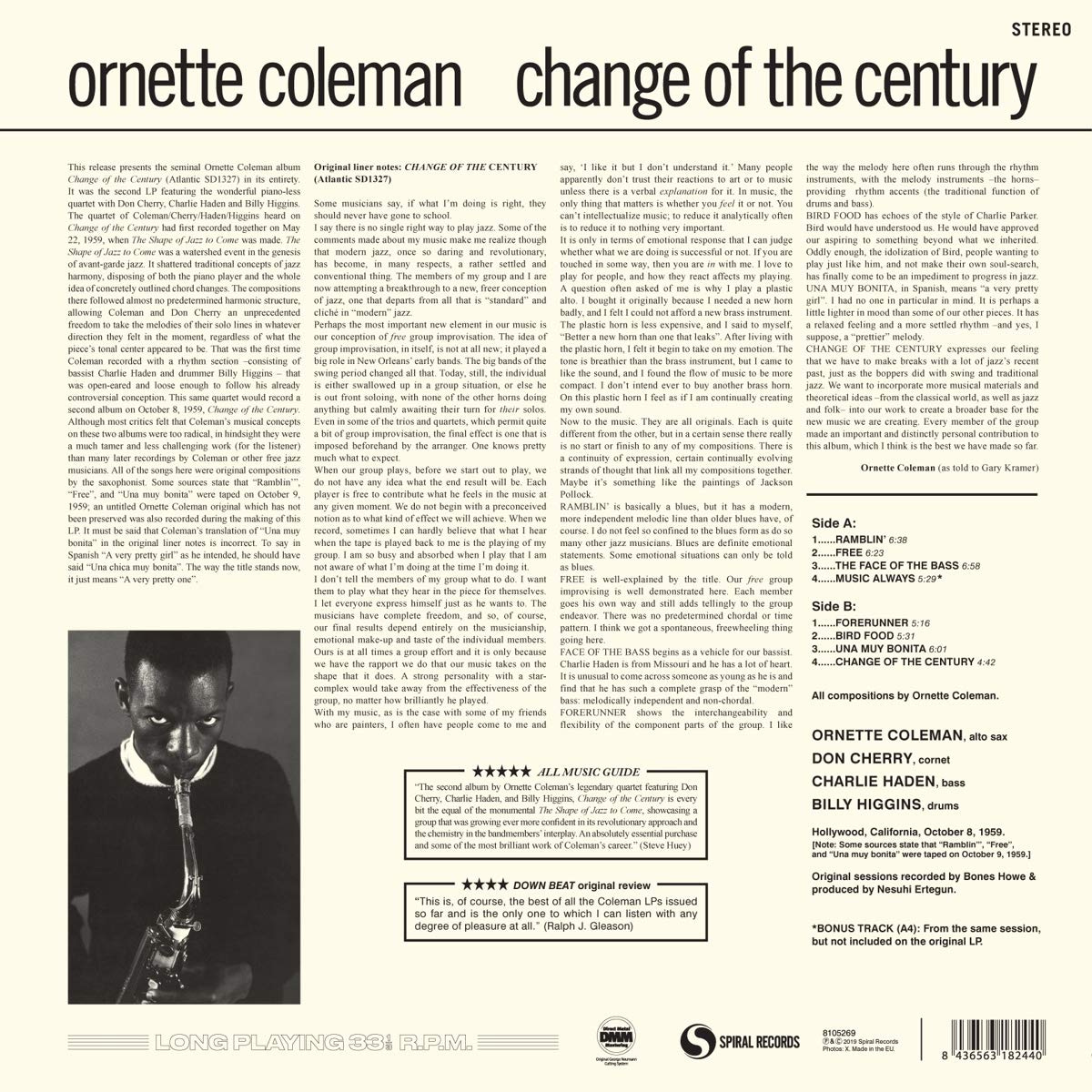

Some musicians say, if what I’m doing is right, they should never have gone to school.

I say, there is no single right way to play jazz. Some of the comments about my music make me realize though that modern jazz, once so daring and revolutionary, has become, in many respects, a rather settled and conventional thing. The members of my group and I are now attempting a break-through to a new, freer conception of jazz, one that departs from all that is “standard” and cliché in “modern” jazz.Ornette Coleman, in the liner notes to Change of the Century

See also: Youth and Age TG 36

[more to come on Thursday, March 24, 2022]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” and “Call Me Larry,” the first eight novellas in Little Follies.

You’ll find an overview of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy. It’s a pdf document.