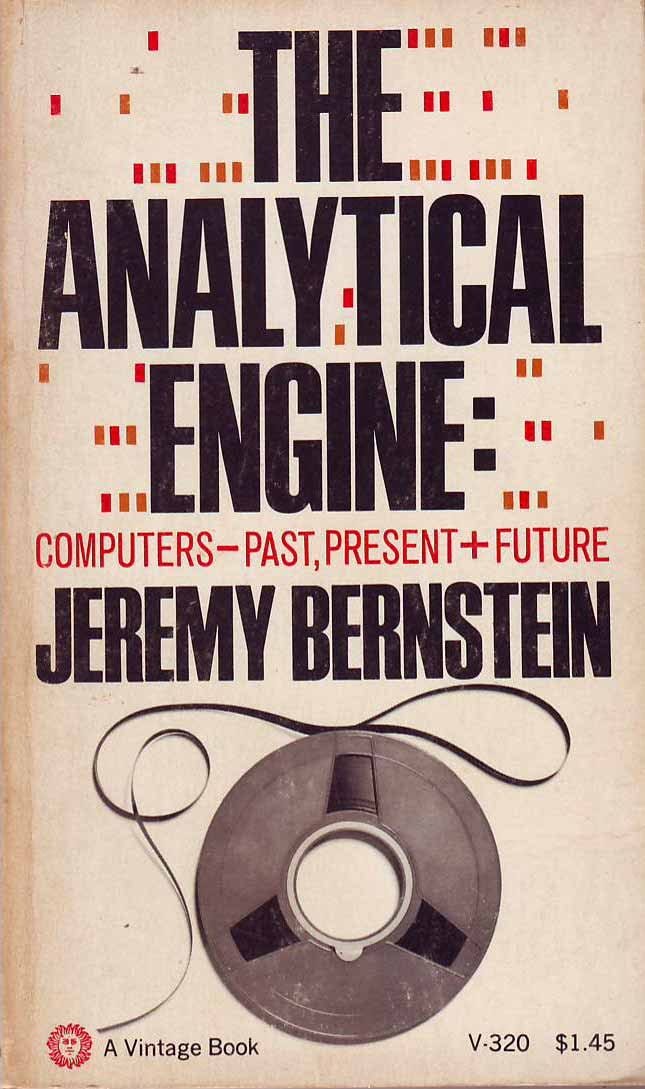

Books, Real and Fictional: Real: The Analytical Engine

In The Analytical Engine, Jeremy Bernstein outlines the project that Lorna described to Herb and Ella:

Herb ’n’ Lorna, Chapter 14

Institutions and Organizations: Real and Fictional: Real

In 1943, the Moore School and the Aberdeen Proving Ground, in Maryland, were conducting a joint project involving the computation of artillery firing tables for the Army. The Moore School contingent . . . used a Bush analog computer and employed a hundred women to do hand computations as a necessary adjunct to the machine operations . . . .

Jeremy Bernstein, The Analytical Engine

J. Presper Eckert and John W. Mauchly, household names in the history of computing, developed America's first electronic computer, ENIAC, to auto mate ballistics computations during World War IL These two talented engi neers dominate the story as it is usually told, but they hardly worked alone. Nearly two hundred young women, both civilian and military, worked on the project as human “computers,” performing ballistics computations during the war. Six of them were selected to program a machine that, ironically, would take their name and replace them, a machine whose technical expertise would become vastly more celebrated than their own.1 The omission of women from the history of computer science perpet uates misconceptions of women as uninterested or incapable in the field. This article retells the history of ENIAC’s “invention” with special focus on the female technicians whom existing computer histories have rendered invisible. In particular, it examines how the job of programmer, perceived in recent years as masculine work, originated as feminized clerical labor. The story presents an apparent paradox. It suggests that women were some how hidden during this stage of computer history while the wartime pop ular press trumpeted just the opposite?that women were breaking into traditionally male occupations within science, technology, and engineering.

Light, Jennifer S. “When Computers Were Women.” Technology and Culture, vol. 40, no. 3, 1999, pp. 455–83. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25147356. Accessed 30 Sep. 2022.

See also: Books, Real and Fictional TG 99

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.