“Inspiration”

THEREFORE, IT IS NOT SURPRISING that when I found myself bored, when I didn’t know what to do with myself, when I was a little on edge and needed to find or devise a way to relax, or even when I was just looking for a way to pass the time, I sought inspiration in junk.

Most of the time, I found it there.

See also:

“Inspiration” TG 125, TG 447, TG 528; and Transformation TG 78

Chance

Where Do You Stop? Chapter 3:

I HAVE SAID IT BEFORE: so much depends on chance.

See also:

Chance (see also Coincidence; Fate; Luck) TG 9; TG 162

Philosophical Concepts: Das Ding an Sich

Where Do You Stop? Chapter 3:

Happy accidents had presented me with the ding an sich and a tacit invitation to make of it whatever I would. Its life as a record player was over, but there was a vital spark in the old gadget yet. All I had to do was discover its true, deep, hidden, or overlooked utility.

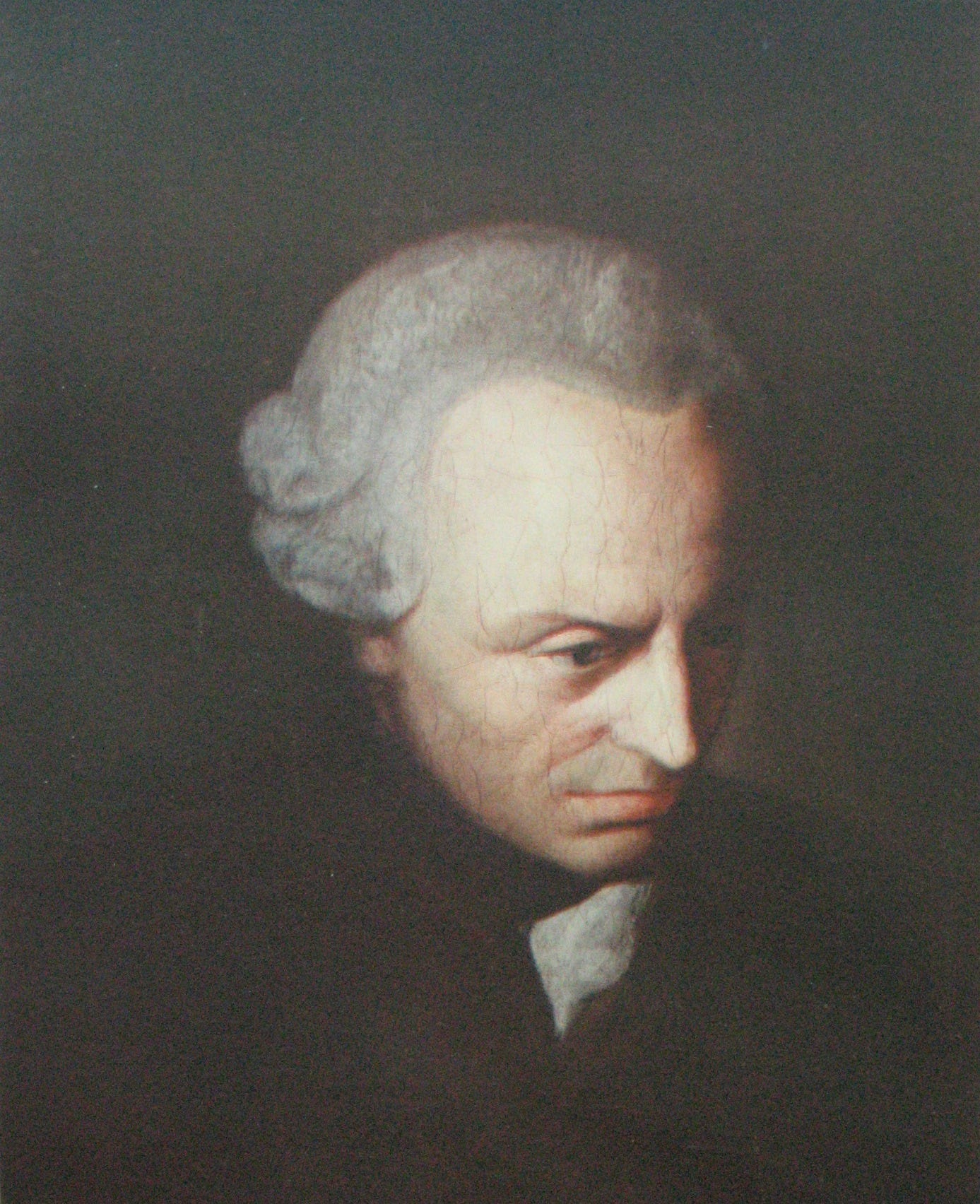

Ralph Blumenau, “Kant and the Thing in Itself,” in Philosophy Now:

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Immanuel Kant significantly extended the range of a priori truths. He held that we bring to bear on the world not only our senses, nor only those a priori truths which unfold from definitions. The way in which our minds operate on the world is dictated by the way our minds are constituted, and this constitution is also a priori, that is, it does not derive from experience, though, like the unfolding of definitions, it will subsequently be applied to experience. […]

When the mind looks at the world, it has no choice but to view it with ideas that are built into the mind. This looking Kant called Anschauungen. The German noun means quite literally ‘viewings’; and the technical translation into English, ‘intuitions’, does not in its everyday sense capture that meaning at all, although it does come from the Latin intueri, meaning to ‘look upon’. Leibniz had called these ideas ‘tools of understanding’; Kant called them Concepts and Categories, and they, too are a priori: that is to say they come before any experience and they shape the experiences we subsequently have. […]

So the world reaches us already mediated through these tools of understanding. And what follows from that is that we can have no direct knowledge of the world as it is before this mediation has happened. The world as it is before mediation Kant calls the noumenal world, or, in a memorable phrase, Das Ding an sich, a phrase which literally means “The thing in itself”, but whose sense would be more accurately caught by translating it as “the thing (or world) as it really is”(as distinct from how it appears to us). He calls the world as it appears to our senses (after mediation through our tools of understanding) the phenomenal world.

See also:

Philosophical Concepts: The Harmony of the Spheres TG 92

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, and Reservations Recommended.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.