Real Reality and Fictional Reality; Imagination; Mind of the Author, the

OF THE DIFFICULTIES that arose during the writing of “The Static of the Spheres,” no other posed so intriguing a set of challenges as the need to create a preoccupation for Guppa, something that he could do in his living room of an evening, in the quiet hours after dinner, that would be the equivalent of his practicing culling clams … but in “My Mother Takes a Tumble” I had made Guppa a Studebaker salesman rather than a foreman in the culling section of the clam-packing plant, and now I felt that I was stuck with that story, just as I found myself stuck with the little lie about the hard candies that my great-grandmother offered me in “Do Clams Bite?” So, I worked out a comparable kind of practice for a Studebaker salesman of the first rank: categorizing potential buyers according to the sales pitch most likely to succeed with each—culling of another sort.

Little Follies, “The Static of the Spheres”

Is what follows a “spoiler”? No. Is it a “teaser”? No. It’s a “sneak preview.”

The following diagram illustrates in schematic form the situation of the author within the world and of the worlds within the author’s brain, including the author’s imagination. (Perhaps it is even a schematic diagram of the so-called author function.)

The area outside the outermost ring represents the ambient reality through which the author moves and from which he gets everything that he knows of everything there is; this is what Emerson called “the actual world—the painful kingdom of time and place.”

I know something from the actual world that is almost certainly the “inspiration” for Guppa’s “preoccupation” in “The Static of the Spheres.”

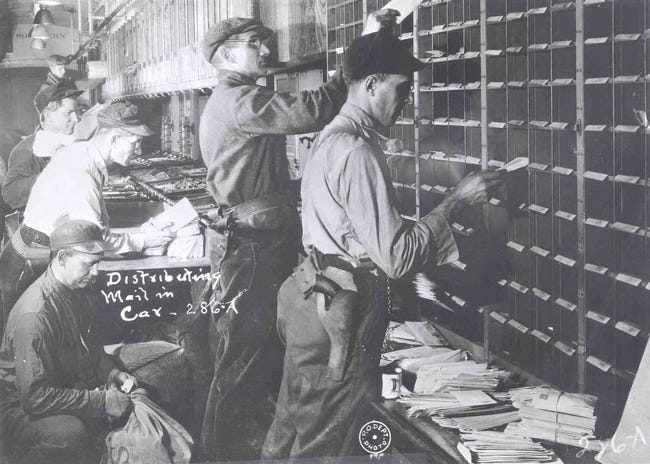

Here it is: Eric Kraft’s maternal grandfather, Clifford Lyman, was a railway mail clerk. He traveled by train up and down the East Coast, sorting mail. He was away from home for two weeks at a time, living in the caboose of a train and sorting mail in the mail car every day. Then he had two weeks off—two weeks when he could spend hours tinkering in his basement workshop, often accompanied by his grandson.

Railway mail clerks had one of the toughest jobs in the Post Office Department, sorting mail on swaying and lurching trains from 1864 to 1977. … Trains derailed because of open switches, livestock on the tracks, on-coming trains, broken rails, and washouts, to name a few things. … From the 1870s to the 1950s, railroads were the primary mode of mail transportation in the United States. To speed delivery, clerks rode in the cars, sorting mail en route. In 1921, due to a rash of train robberies following World War I, Postmaster General Will H. Hays armed railway mail clerks, ordering them to shoot to kill to protect the mail. … RPO [Railway Post Office] interiors typically ranged from 15 to 60 feet long and were about 9 feet wide. Tight-knit crews of up to 20 men worked in the larger cars, racing the clock to sort mail in time for dispatch to the stations en route. “Working the mail” consisted of sorting letters into “pigeon hole” distribution cases and tossing mail accurately into labeled pouches, correctly routed to as many as 5,000 destinations. … Clerks had to memorize complex distribution schemes and studied and practiced continuously in order to pass regularly-scheduled examinations. … In the 1950s and 1960s, improved highways, affordable automobiles, and the growing airline industry contributed to a decline in passenger train service. Fewer available trains, along with modern letter sorting machines that rendered much hand-sorting of mail obsolete, spelled the end of an era. On July 1, 1977, at 4:05 a.m., the last Railway Post Office ground to a halt at Union Station in Washington, D.C., after a 5-hour journey from New York City.

Keep that in mind as you read “The Static of the Spheres.”

[more to come on Monday, August 9, 2021]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can catch up by visiting the archive.

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?” and “Life on the Bolotomy,” the first three novellas in Little Follies.