Persistence

Endurance

Where Do You Stop? Chapter 37:

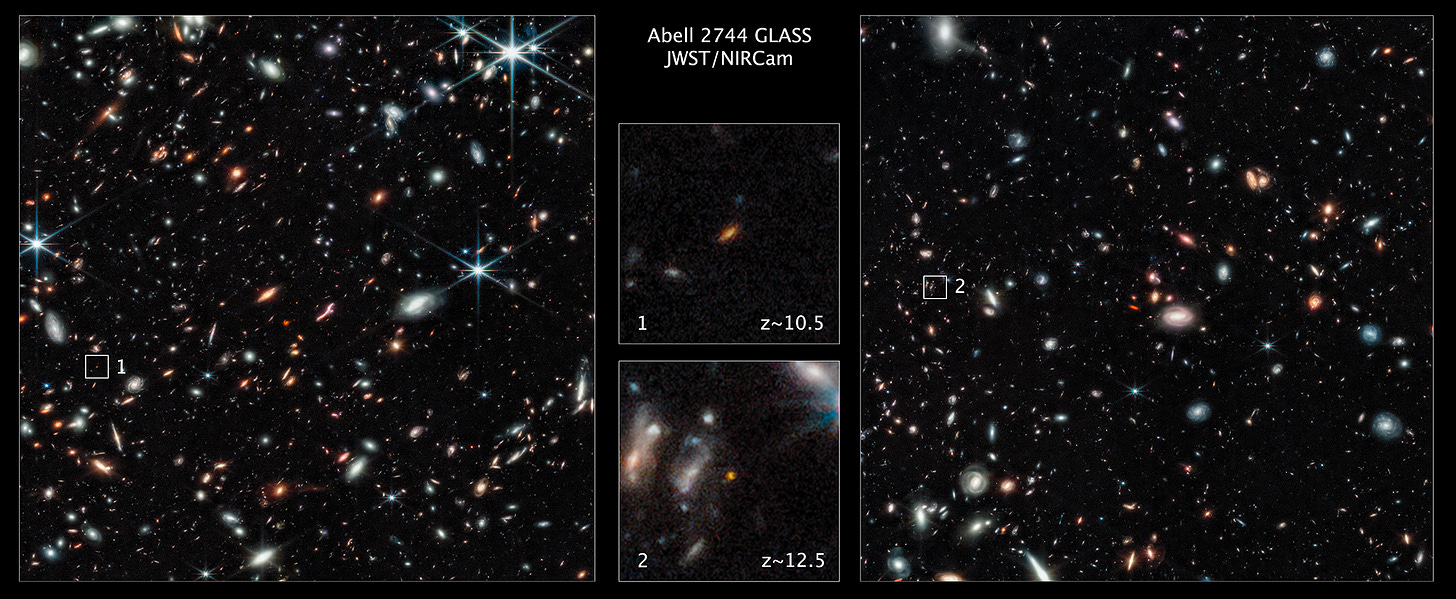

BECAUSE THE UNIVERSE IS EXPANDING, and, as Quanto pointed out, most of everything is nothing, every day, every moment, more nothing separates the rest. With more and more Zwischenraum, the universe is becoming more and more transparent. When Raskol sprayed me with that beam of photons from the flashlight, some of them were reflected outward, arranged in a pattern imposed on them by the contours of my face. Many of them never made it out of the atmosphere, of course—they collided with molecules of this and that, got transmuted, caused transmutations—but the number of photons in that beam was enormous, and lots of them got away. […] From there on, the odds that the photons reflected from me would survive got better and better, and the odds in their favor have improved every day, and continue to improve, as their obstacles drift farther and farther apart in the expanding universe, making it a little more likely every day, every moment, that at least some of them will continue rushing on and on, for something like forever, or as close to forever as the universe itself will ever come […], and so, perhaps, in that one sense, there is no end of me, I do not stop.

Wilhelm Nero Pilate Barbellion (Bruce Frederick Cummings), The Journal of a Disappointed Man (1919):

I have revelled in my littleness and irresponsibility. It has relieved me of the harassing desire to live; I feel content to live dangerously, indifferent to my fate; I have discovered I am a fly, that we are all flies, that nothing matters. It’s a great load off my life, for I don’t mind being such a micro-organism—to me the honour is sufficient of belonging to the universe—such a great universe, so grand a scheme of things. Not even Death can rob me of that honour. For nothing can alter the fact that I have lived; I have been I, if for ever so short a time. And when I am dead, the matter which composes my body is indestructible—and eternal, so that come what may to my “Soul,” my dust will always be going on, each separate atom of me playing its separate part—I shall still have some sort of a finger in the Pie. When I am dead, you can boil me, burn me, drown me, scatter me— but you cannot destroy me: my little atoms would merely deride such heavy vengeance. Death can do no more than kill you.

George Gamow, One, Two, Three . . . Infinity: Facts and Speculations of Science (1947):

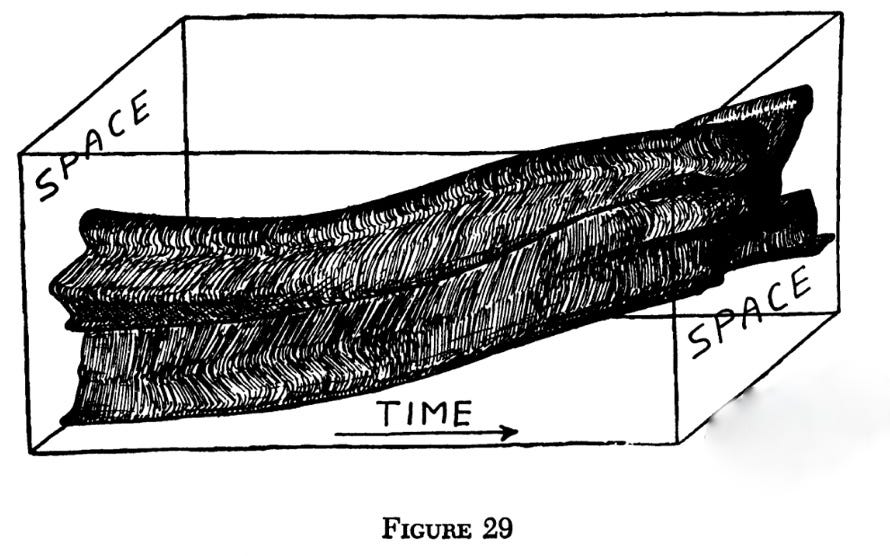

Think of yourself as a four-dimensional figure, a kind of long rubber bar extending in time from the moment of your birth to the end of your natural life. Unfortunately one cannot draw four-dimensional things on paper, so that in Figure 29 we have tried to convey this idea by an example of a two-dimensional shadow man taking for the time-direction the space-direction perpendicular to the two-dimensional plane on which he lives. The picture represents just a small section of the entire life span of our shadow man. The entire life span should be represented by a much longer rubber bar, which is rather thin in the beginning, when the man is still a baby, runs wiggling through the period of many years of life, attains a constant shape at the moment of death (because the dead do not move), and then begins to disintegrate. […]

To be more exact we must say that this four-dimensional bar is formed by a very numerous group of separate fibers, each one composed of separate atoms. Through the period of life most of these fibers stay together as a group; only a few of them fall away, as when the hair or the nails are cut. Since the atoms are indestructible, the disintegration of the human body after death should be actually considered as the dispersion of the separate filaments (except probably those forming the bones) in all different directions.

[BTW: I invite you to return to the beginning of Where Do You Stop? and re-read the epigraphs. Wait a minute: why would I make you do that when I could just reproduce the epigraphs here? Here they are. —MD]

Bazarov, in Ivan S. Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons (translated by Bernard Guilbert Guerney):

Here am I, lying under a hayrick. The tiny narrow spot I’m taking up is so infinitesimally small by comparison with the rest of space, where I am not and which has nothing to do with me, and the portion of time which I may succeed in living through is so insignificant when confronted with eternity, wherein I was not and shall not be. Yet within this atom, this mathematical point, the blood is circulating, the brain is working, something or other yearns. . . .

Victor F. Weisskopf, “Niels Bohr, the Quantum, and the World” (from Niels Bohr: A Centenary Volume):

The interaction between thought and language always fascinated Bohr. He often spoke of the fact that any attempt to express a thought involves some change, some irrevocable interference with the essential idea, and this interference becomes all the stronger as one tries to express oneself more clearly. Here again there is a complementarity, as he frequently pointed out, between clarity and truth—between Klarheit und Wahrheit, as he liked to say. This is why Bohr was not a very clear lecturer. He was intensely interested in what he had to say, but he was too much aware of the intricate web of ideas, of all possible cross-connections; this awareness made his talks fascinating but hard to follow.

Frank Close, Michael Martin, and Christine Sutton, The Particle Explosion:

Electrons exist both on their own, as free particles, and as constituents of atoms, and they can change from one role to the other and back. An electron forming part of a carbon atom in the skin of your wrist could be knocked out of position by a passing cosmic ray and become part of the tiny electric current in your digital wristwatch, and then in turn become part of an oxygen atom in the air you breathe as you raise your arm to look at the time.

H. Kumar Wickramasinghe, “Scanned-Probe Microscopes” (Scientific American, October 1989):

In the [scanning tunneling microscope] the “aperture” is a tiny tungsten probe, its tip ground so fine that it may consist of only a single atom. . . . Piezoelectric controls maneuver the tip to within a nanometer or two of the surface of a conducting specimen—so close that the electron clouds of the atom at the probe tip and of the nearest atom of the specimen overlap.

Manfredo Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s:

Simmel, on the basis of a partial reading of Nietzsche, recognizes this in his Metaphysics of Death: “The secret of form lies in the fact that it is a boundary; it is the thing itself and at the same time the cessation of the thing, the circumscribed territory in which the Being and the No-longer-being of the thing are one and the same.” If form is a boundary, there then arises the problem of the plurality of boundaries—and the calling them into question.

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities (translated by Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser):

The right thing and the time it takes are connected by a mysterious force, just like a piece of sculpture and the space it fills.

[And here are some reviews.]

Walter Satterthwaite, The New York Times Book Review:

The title of this sly and extremely funny book is also the title of a paper that Peter is assigned by his science teacher, the luscious, leggy Miss Rheingold. We — and Peter — learn quite a bit about Miss Rheingold, although nowhere near as much as Peter would like. We also learn about epistemology; the boundaries of the self; the building of backyard lighthouses; terrazzo floors; Chinese Checkers; American education; the restricted vision of children (and their parents); and the design of such exquisitely intricate gadgets as the phonograph, the scanning tunneling microscope, the universe, and the novel. . . .

Literary echoes reverberate down the corridors of The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy—Sterne, Melville, Mark Twain, Proust, Borges, Nabokov, Gabriel Garcia Marquez—but they reverberate lightly, whimsically. Mr. Kraft is his own man, with his own somewhat loopy agenda. He writes an elegant, supple, uncommonly precise prose that glides, silk-smooth, from pathos to parody, from slapstick to sentiment, from the mysteries of moonlight on Bolotomy Bay to the mysteries of particle physics. Toward the end of [this] book, he creates several scenes involving Peter and Ariane, the sultry older sister of Peter’s best friend, Raskol. Each vignette is a perfectly balanced blend of slightly edgy comedy and shrewd observation; and each is also extraordinarily sexy. The unattainable Ariane is breathtakingly desirable, and Peter’s desire — the awful, ecstatic ache of preadolescence — is rendered so artfully that it becomes almost palpable.

In what other novel . . . will you find the instructions, complete with diagram, for constructing a flour bomb? Or a discussion, by a gum-chewing seventh-grade girl, of Zwischenraum, the empty space between the components of an atom? Or a canny analysis of racial prejudice proffered by Porky White, the entrepreneur behind the phenomenally successful Kap’n Klam Family Restaurants?

Like childhood itself, Where Do You Stop? is filled with wonders. It is a book designed to leave its readers — and it deserves many of them — as happy as clams.”

David Foss:

The enigmatic title of this amusing, yet thought-provoking, novel can be interpreted in many ways, including, “Where do you stop once you start to identify themes in this book?” Yet all those themes are beautifully linked via Kraft’s clever, sometimes hilarious, prose, demonstrating his narrator’s realization (at the age of 10) that all knowledge, sacred and profane, macro and micro, is interrelated. Our genial adult host, Peter Leroy, in recalling his experiences as a seventh-grader discovering quantum physics and sex (and their nexus points), gently guides us from the universal to the subparticular and back again, while simultaneously charting his younger self’s almost imperceptible transition from childhood to adolescence (and from one end of the couch to the other). In Where Do You Stop? Kraft shines his light on this world, revealing (as he does in all his books) that life is in the details. Even if those details are hard to pin down (as Heisenberg proved). To cap it off, Kraft skillfully shapes the narrative so that it comes full circle in the final pages, completing the circuit, turning on a light that will shine forever (“or as close to forever as the universe will ever come”). A book to treasure.

“A magical, funny, healing journey.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Warm . . . thought-provoking . . . charming . . . delightful.”

Library Journal (starred review)

“Mr. Kraft is a splendid, smart, funny, slyly sexy, and insightful writer.”

Michael Z. Jody, The East Hampton Star

“Luminously intelligent fun.”

Time

“Goofy and thoroughly enjoyable.”

Timothy Hunter, The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Nothing less than an attempt to comprehend the nature of the universe itself.”

Michael Upchurch, The Seattle Times & Post-Intelligencer

“Hilarious.”

Bruce Allen, USA TODAY

A NEW YORK TIMES NOTABLE BOOK OF THE YEAR

RECOMMENDED BY THE READER’S CATALOGUE

[This episode ends the serialization of Where Do You Stop? The serialization of The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy will continue with the first episode of What a Piece of Work I Am.]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, and Where Do You Stop?

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

I agree with all of the reviewer's that Where Do You Stop is a brilliant novel. I have read it over and over.