THIS DAY, Monday, was the first real working day for Lou’s takeover team, and they spent the day in constant conference, proposing and planning, scheming and dreaming. They were still buzzing after dinner, when we gathered in the lounge, but I silenced them with my reading of “Shame on Me,” episode forty-nine of Dead Air.

FOR MY THIRTEENTH BIRTHDAY, I bought myself a tape recorder. It took all the money I had, but I thought it was worth it. I had just launched my radio career, and I had immediately discovered how very difficult it is to keep talking without pausing longer than a breath. After a couple of days on the air, my voice had degenerated to a rasping croak. With a tape recorder, I could record myself for an hour and then broadcast the recording as often as I liked, filling time with no effort until I had rested my voice and thought of something new to say.

Because I was so eager to give the tape recorder a trial run, I spent the morning of my birthday in the backyard cave that housed my radio transmitter (and my flying-saucer detector, and a receiver tuned to the frequency of the electronic eavesdropper that I had planted in Betty Jerrold’s bedroom). I spent some time recording a few tapes full of random observations about current events in my immediate neighborhood and the actors involved in them, and when I had used all the tape that I had bought I pulled a reel from the stack and put it on the recorder. With no further broadcasting responsibilities for a while, I left the recorder running, transmitting a tape over the vast WPLR network, and I went off to explore the rest of the cave, to see what my fellow troglodytes had done with their parts of it, to snoop, to spy.

The cave was divided into several rooms, dens, or lairs, so that each of us who had built it and used it could have a place of his own. Mine was my broadcasting studio, of course. Marvin’s was nearly empty, a monkish cell that he used for quiet thinking. Spike’s was intriguing, since it was well stocked with what was considered pornography at the time. Raskol’s was full of treasures that he had found unattended during his rambles through Babbington, but after giving them a thorough examination I had to admit that one man’s treasures may be another man’s junk. Matthew’s was the most fascinating den. He called it his sanctum. It was locked, and that was part of its fascination. With the tape recorder running and my voice broadcasting the length of Babbington to camouflage my espionage, I set about, deliberately, penetrating the secret of Matthew’s sanctum — that is, breaking in. Its boy-built door was secured with a boy-built lock. I picked the lock and let myself inside.

It was a shrine. At first, I thought it was simply a shrine to his father, because what I noticed first were the pictures of his father hanging on the back wall. I had never seen any pictures of Matthew’s father before, but I could tell at once that the man I saw in these pictures had to be his father, because he looked just like Matthew, an older Matthew, but not that much older, a man, but a man in whom the boy has been allowed to linger, has not yet been sent to his room once and for all. Most of the pictures were snapshots, but one, a remarkable one at the center, was a drawing in pastels of his father in his flight jacket. The dampness of the cave and a leak in its boy-built roof had damaged the picture: a water mark ran down the left side. Most of the pictures were of his father alone, but some were of his father and mother, and three of them had been altered to include Matthew with his father and mother. We all knew that Matthew’s father had been killed in World War II without ever seeing his son, but here Matthew had created the photographs that might have been; he had cut himself from other snapshots and inserted his image in pictures of his parents. Interspersed with these pictures of affection and wishful thinking, he had arranged pictures of war and death. One showed a grimacing gunner shooting at something outside the frame of the photograph — shooting at anything or anyone — and another showed a young antiaircraft gunner, dead at his post, twisted unnaturally, thrown to the ground like a dummy tossed into a box. The room was a shrine not only to the memory of his father but to the mother-father-son family that his had never been, and it was also a subterranean reminder of the madness that had taken his father from him.

I didn’t belong there. I had insinuated myself into a place where I did not belong, from which I and everyone else had been excluded, and I was ashamed of myself for doing it. I backed out of the room, shut the door, and reset its clever lock, covering my tracks as I went, so that I wouldn’t leave a trace of my transgression.

THERE WAS A QUESTION after the reading. It came from Miranda. “You’ve kept that memory all these years,” she began, “but do you feel free of it now?”

“No, no,” I said, “not at all. I write to remember, not to forget.”

Subscribe to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy

Share The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy

Watch Well, What Now? This series of short videos continues The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy in the present.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

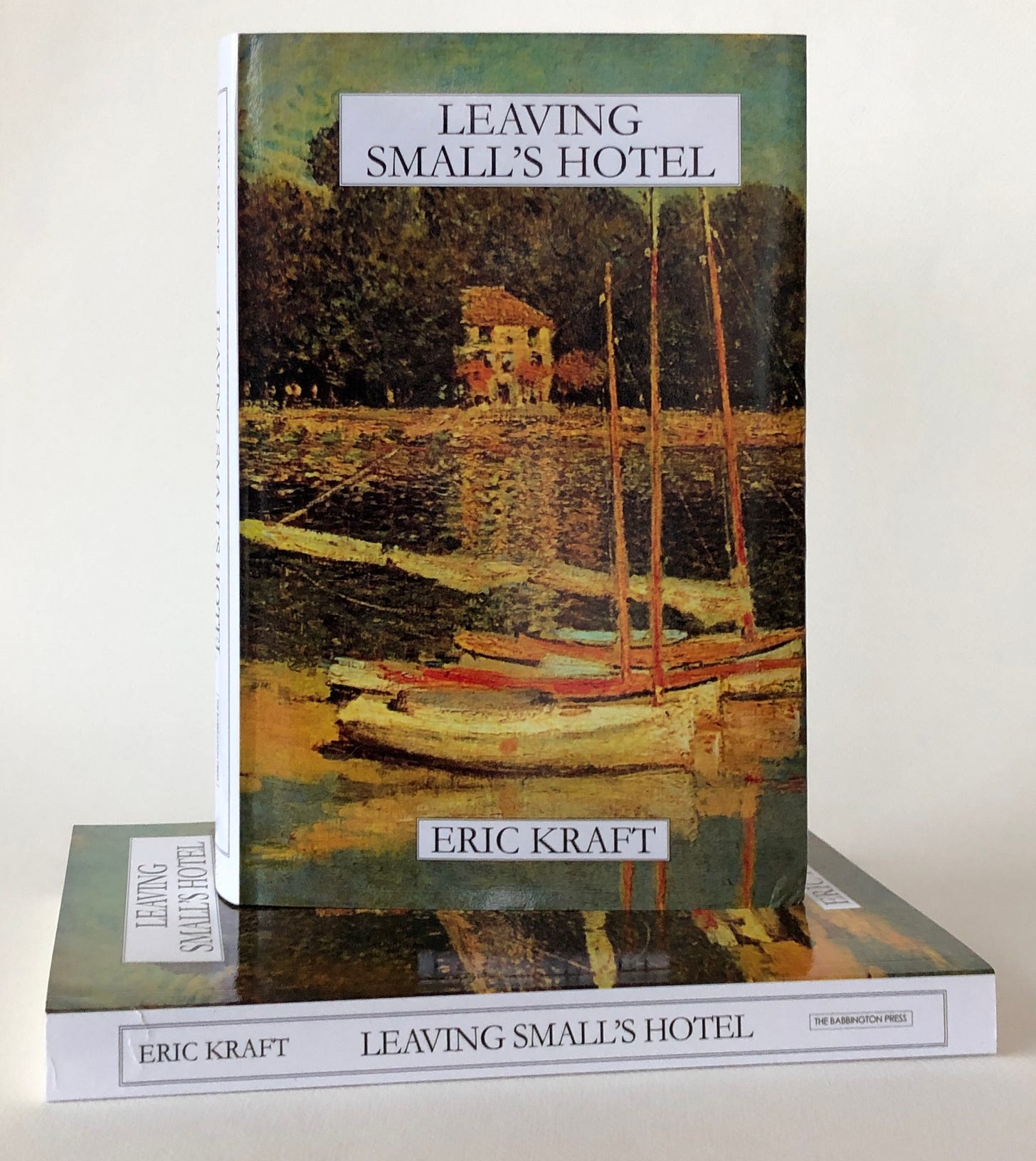

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, Where Do You Stop?, What a Piece of Work I Am, and At Home with the Glynns.

You can buy hardcover and paperback editions of all the books at Lulu.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post