THE GROUP that lingered in the lounge after the reading couldn’t get off the topic of fallout shelters. Apparently, I had revived for them an old debate that had been suspended but never concluded, the question whether or not one would let others into one’s fallout shelter beyond the number that it had been designed to accommodate. Forty years ago, people couldn’t stop asking one another variations of that question. All versions took the general form of “Would you allow so-and-so into your fallout shelter?” but “so-and-so” could be “someone with an incurable disease who had only a year to live,” “a child,” “a child with only a year to live,” “a pregnant woman,” “a woman pregnant with your illegitimate child,” and so on. There were also less serious versions of this question in which “so-and-so” became a matinee idol or a voluptuous starlet — at least I think they were less serious. All the variations were revived that evening, and new ones were invented, and the conversation went on long into the night — just as it used to.

I couldn’t get a word in edgewise, which was just as well. I had more to say about my grandfather’s cave, but it was probably best not said there in the lounge, where atomic anxieties were taking on the rosy glow of remembered pleasures, and I began expecting someone to sigh and claim that those had been the days.

If I had spoken, this is what I would have said:

I BECAME ASHAMED of my grandfather for concealing the shelter. I thought that it was disgraceful. I was shocked and disappointed and puzzled to hear Guppa talk about the urban refugees he expected. They seemed so real and immediate a danger to him that they seemed to be the enemy, not the people armed with the intercontinental ballistic missiles. The anticipated refugees were nearer, and so they seemed more real. I was naive and hopeful enough at the time to think that in Guppa’s place I would have chosen to save them all. The fact that saving them all would require a back yard considerably larger than Guppa and Gumma’s was not material to my thinking. It was the principle that counted, not the practicality. Guppa had never been very practical, so it seemed to me that he could afford to be principled.

Suddenly, as I write those words, the time that I’m recalling seems very long ago. Let me say right now, before I take you back there with me, that when we get there I am going to start something at the family dinner table that will certainly lead to an argument, and that I know it will be my fault. Here’s the situation in brief: my father had been in control of my family, including me, for as long as I could remember, and he had intended to rule for life, but when I began approaching thirteen, I initiated a campaign of guerrilla warfare. I was revolting.

Dinners were difficult at that time, most especially difficult for my mother, and it was almost always my fault that they were difficult for her. I brought anger and restlessness to the table; my father brought anger and disappointment; and my mother brought a pack of cigarettes and a bottle of tawny port. Generally, we tried to eat in silence, since we all knew that any conversation was likely to lead to an argument, but one of us did not know how to hold his tongue.

“You know Guppa’s fallout shelter?” I said into the silence.

“Uhh,” said my father.

“Well, I was wondering — ”

A pause. Perhaps my father was wondering too, wondering whether I had something that I really wanted to ask him, in which case it might be the case that I had come back to the realization that he was the boss and that as the boss he was also the living repository of all important information, or whether this claim to wonder was just the bait in a trap.

He took the bait. “Wondering what?”

“You know, whether he really considered, you know, the morality of it.”

“What morality is that?”

“Well, you know, Guppa thinks that people are going to come swarming from the city trying to save themselves.”

“Sure.”

“Well, does he think, you know, that those people are bad somehow for wanting to save themselves?”

“How the hell would I know? Why don’t you ask him?”

My mother sighed and said, “Bert — ”

“Ella, don’t you see that he’s not interested in what I think? He’s just baiting me.”

“No, I’m not,” I lied, using the voice of the offended innocent.

“All right, go ahead,” he said. “Get to the point.”

“Well, I mean, from Guppa’s point of view their motives can’t be wrong, since they’re the same as his own.”

“All right.”

“Well, I’ve been thinking about this, and I know that Guppa, like most working people, considers theft of labor a greater crime than theft of property, so — ”

“Now, wait a damn minute!”

“What?”

“What in the name of blazes do you know about ‘working people’ — or work?”

“Well, I — ”

“What did you do — watch somebody doing a day’s work and now you think you know what makes ‘working people’ tick?”

“No, I — ”

“There’s more to work than watching, you know. That’s your favorite expression, I’ve noticed, you know?”

“Well — ”

“That’s another one! Well! Well, you know! And here’s another one: I’ve been thinking! Sometimes you get started with ‘well, you know,’ and ‘I’ve been thinking,’ and I say to myself, ‘Oh, Jesus, here we go!’”

Silence fell over the table again. My mother pushed her plate away from her and settled back in her chair. She shook a cigarette from her pack and lit it. She took a long drag, and as she exhaled she poured herself another half glass of tawny port.

I cleared my throat and said, “Well — ”

My father gave me a hard look.

“ — you know — ”

He put his fork down.

“ — I’ve been — ”

He reached across the table and picked up my mother’s pack of cigarettes.

“ — giving this a lot of thought — ”

He lit a cigarette and frowned in my direction.

“ — and I decided, or I think I decided, that, maybe, the evil of the people fleeing the city must be that they want to use shelters that other people built and prepared —”

“Of course,” said my father, blowing smoke.

“ — at the expense of great effort and ingenuity.”

“Of course, of course.”

“But here’s the thing: those people never wanted a shelter — theirs or anybody else’s — until the bomb fell.”

“What?” said my mother, startled.

“He means if,” said my father, “if the bomb fell.” He stubbed out his cigarette, though he hadn’t finished smoking it. I knew what that meant. He was going to leave the table in a moment, so he would tell me to get to the point, and he would remind me that I had work to do.

“Get to the point, Peter,” he said. “You’ve got the dishes and your homework to do.”

“And you’ve got your beer to drink and the television to watch,” I muttered.

“What did you say?”

“Nothing,” I said.

“Get started on those dishes.”

He got up from the table, got a can of beer from the refrigerator, and went into the living room.

My mother and I eyed each other. I wanted to go on talking — I usually wanted to go on talking — but I had caused trouble, and I knew it, and I thought that my mother might not want to hear anything more from me, so I didn’t say anything, but she was my mother, so, after a moment of weary silence, she said, “Go ahead, Peter. Tell me what you were getting at.”

“I’m not sure what I was getting at, really,” I said. “I don’t know whether I have a point — but I have a lot of questions.”

“Oh,” she said, frowning. I think she had hoped that listening would be enough, that she would be able to let me talk, with nothing more required of her, but questions implied answers.

I shrugged and said, “I’m not sure that my questions have any answers.”

“Oh,” she said, smiling. “Well, why don’t you go ahead and ask them.”

“Okay,” I said. “First question: if urban refugees did come swarming into Babbington looking for someone’s fallout shelter, wouldn’t it be because they had been pushed into it?”

“Pushed into it?”

“You know, because the bomb drove them from the city — pushed them out.”

“Oh. I see. Yes, I guess so. You’re right.” I had the feeling that she had the feeling that we were practicing for a quiz show.

“Okay, second question: they wouldn’t necessarily be evil, would they, those people?”

“No. No, they wouldn’t.” She looked around the room with apparent urgency, and I had the crazy idea that she was looking for a pad so that she could keep score.

“Third question: they could even be good people who had been displaced by evil, couldn’t they?”

“Yes!” she said, and she jumped up from the table. “Wait a minute, Peter. I want to get a pad from the kitchen and write some of this down.”

“Okay.” She dashed into the kitchen, where she took from a drawer the pad she used to make her shopping list. She stood there at the kitchen counter for a while, writing rapidly and then came back into the dining room, reading what she’d written as she walked, and settled into her chair, still with her eyes on the pad.

“Okay,” she said. “Go ahead.”

“Let’s see,” I said. “Third question — ”

“No, no. We had the third question: ‘Couldn’t they be good people dispossessed by evil?’”

“‘Dispossessed’? I said ‘displaced.’”

“Oh,” she said. She started to erase it.

“But ‘dispossessed’ is kind of — interesting. Better.”

She was surprised and pleased. “It’s sadder,” she said, “and kind of — ”

“Surprising,” I said.

“Yes. It is surprising.”

“That’s because it’s not what you expect. I mean, people are usually possessed by evil, so when you hear dispossessed, it sounds like a mistake at first, and then when you think about it, you realize that it isn’t a mistake, that it’s right, it’s true.”

“And because it sounds like a mistake at first you have to think about it, so it’s — well, you know — it’s clever, isn’t it?”

“I think so.”

“‘Dispossessed by evil,’ she read from her pad. She looked at me suddenly, and she seemed startled. “In fact,” she said, “they would be a kind of fallout themselves, wouldn’t they — you know, a kind of human dust blown far from home by the fireball of evil?” She looked into the distance.

“Well,” I said. “I don’t know. That’s a little — ”

She held her hand up for me to stop.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “You really do have to get to work on your homework.”

“And the dishes,” I said.

“That’s all right. I’ll do them. I’ll let them drain, and you can put them away when your homework is finished.”

“Okay,” I said. I left for my room, but I made a detour to the bathroom. When I came out, I stuck my head around the corner of the kitchen to thank my mother for doing the dishes, but she wasn’t at the sink. She was still in the dining room, but not at the dining room table. She had moved, with her cigarettes and her glass of tawny port, to the little table in the corner where our telephone was.

“Dudley?” she was saying, in a low, husky voice. “It’s Ella. Oh, nothing. It’s just that, well, you know, I was thinking — about fallout shelters — and — you know — the morality of them. Morality. Well, I’m not sure I have a point, but — you know — I have a lot of questions — ”

I went upstairs and did my homework. When I came back down to the kitchen later to put the dishes away I found that they hadn’t been done. My mother must have gone to bed and forgotten them. I did them.

[to be continued]

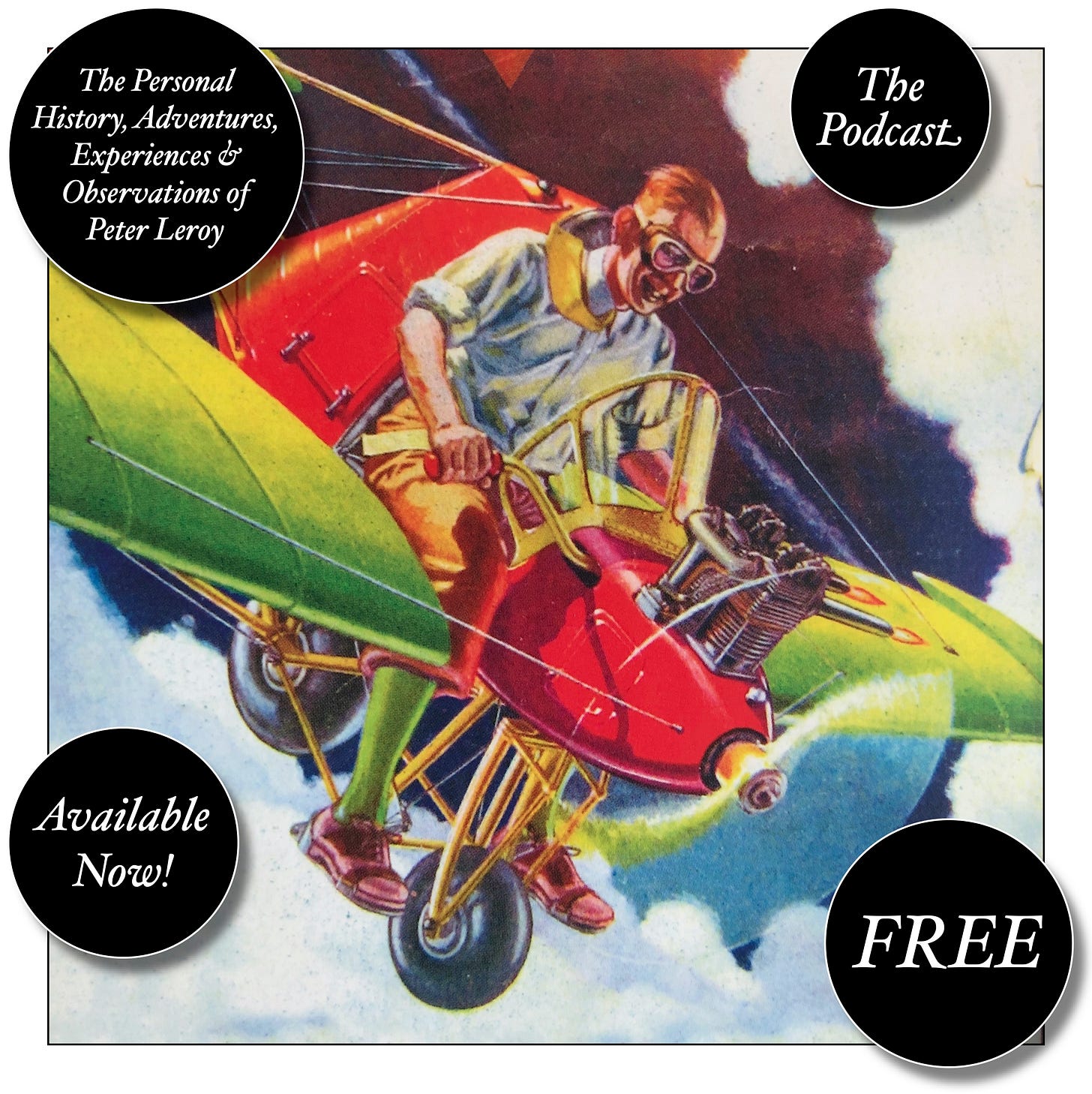

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, Where Do You Stop?, What a Piece of Work I Am, and At Home with the Glynns.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.