MY AUDIENCE for the reading of the twentieth episode of Dead Air, “Gratitude,” consisted of the inmates of Small’s Hotel (Albertine, Lou, Elaine, Clark and Alice, Artie and Nancy, Otto and Esther, Louise and Miranda), Suki and her boyfriend Daryl, and a quartet of Babbingtonians who stayed on after Sunday dinner.

ONE NIGHT, a couple of months before I turned thirteen, I decided to believe in flying saucers after seeing five of them and a naked woman while I was carrying the garbage cans out to the curb, which I was supposed to have done right after I had finished the dishes but had postponed for a television show that I wasn’t ordinarily allowed to watch. I had fallen asleep in front of the show, and my father hadn’t wakened me until he and my mother were ready for bed, so I had to drag myself out at an unaccustomed hour. I carried the cans to the curb, and when I had put the last of them in place, I looked up and down the street. All the houses were dark but one, the Jerrolds’ house. There, the lights were on in one room on the second floor. That room, I believed, without giving it a thought, was Mr. and Mrs. Jerrold’s bedroom. I turned toward my own house and began to walk toward my own bed, when my mind suddenly produced an interpretation of visual details that a moment earlier had made hardly any impression on me at all but now, figuratively, grabbed me by the shoulder and spun me around. I looked up at the Jerrolds’ house again. Mrs. Jerrold had been standing in the window, naked. She was gone now, but she had been there. I was sure of it. I believed it.

I wonder how old Mrs. Jerrold was at that time (when nearly everyone was an insomniac, tossing and turning through night after night of sweaty anxiety brought on by fear and uncertainty: fear of spacecraft and the unknown beings that inhabited them and fear of intercontinental ballistic missiles and the warheads we knew they carried, and uncertainty over which would do us in first). I suppose I could figure out how old she was. She was the mother of a boy who was younger than I, so she probably was younger than my mother, and my mother was a young mother. She had given birth to me when she was still a teenager, so she would have been only thirty-one or so at that time. Mrs. Jerrold may have been thirty. Perhaps she wasn’t yet thirty.

She had a trim figure. I put it that way because that is the way my father always put it. The Jerrolds had moved into the neighborhood several years after we did. Their house had been there when we arrived, but someone else was living there. I can’t remember who it was, and because I can’t remember who it was I suspect that it must have been an old couple with no children my age and no interest in children my age. If they had had children my age, or if they had been interested in forming a grandparently attachment to a child my age, then I think I would have found my way into their house and life, but I never did, and so I suppose that there was no interest in either direction. They probably died, and then the Jerrolds bought the house.

When I bring Mrs. Jerrold to mind, she is wearing a shirtwaist dress. She can’t always have been wearing a shirtwaist dress, of course, but when I see her in anything else, I know that I am imagining it, not remembering it (partly because the something elses tend to be pink nighties and two-piece bathing suits), so I make the effort to push the imagined images aside in favor of the ones I have confidence in, and in those she is always wearing a shirtwaist dress. She has put it on in haste, after daytime sex.

She was trim and leggy, and she was cool. She didn’t seem to hurry, and she didn’t seem to sweat. She favored barer fashions than the other women on the block. There was always a little more of Mrs. Jerrold available for viewing than there was of the others. She may have been proud; maybe she saw herself as more attractive and sexier than the other young matrons, and so showed off a little. I was grateful.

I turned toward my house again. Above me, above a corner of the house, was a single glowing ring, hovering. In a moment, four other rings emerged from it, as if they had been stacked atop one another. They formed a V, paused a moment, and then rushed away to the east, over the house and out of sight. I looked back at the street. I suppose I expected to see the neighbors, including Mrs. Jerrold, rushing out of their houses in their nightclothes. The light went out upstairs at the Jerrolds’. I wondered whether Mrs. Jerrold would sleep well. Would her sleep be troubled by saucer anxiety? I could help her. I had the solution: from plans that I found in Cellar Scientist magazine, I had built a flying-saucer detector that allowed my mother to sleep tight while it stood watch on her bedside table, detecting an absence of menace. If I visited Mrs. Jerrold the next day and told her about the squadron of saucers I had seen, she would be alarmed and she would be anxious, but when I gave her my detector and explained that it would make her nights peaceful, that it would allow her to snuggle into her bed and sleep, she would be grateful to me, and I would be grateful to the saucers, and gratitude is an entirely sufficient basis on which to build a belief.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

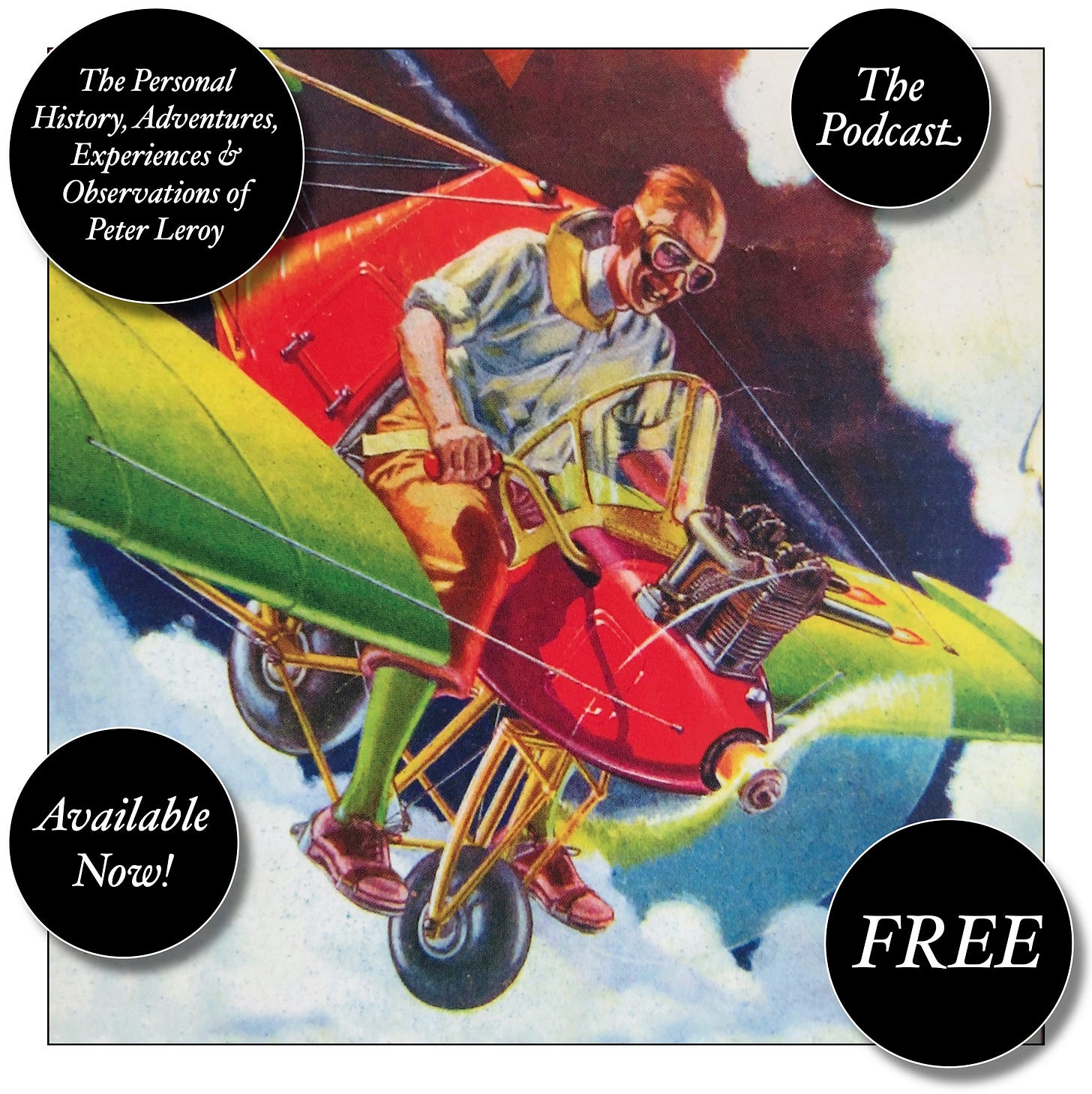

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, Where Do You Stop?, What a Piece of Work I Am, and At Home with the Glynns.

You can buy hardcover and paperback editions of all the books at Lulu.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post