FOR MY READING of “The Hole and the Hill,” episode thirty-nine of Dead Air, I had quite a sizable audience. The Friday turnout for dinner and drinks was very good, and we acquired seven new resident guests in the afternoon: my old friend Mark Dorset; both of his ex-wives, Margot and Martha Glynn; their daughters, Martha and Margot, each daughter named for her aunt; and the daughters’ husbands, our sons, Edward and Daniel.

WITH MY FRIENDS Raskol, Marvin, Spike, and Matthew, I operated a radio network quite a few years ago, when we were all about thirteen. Our worries about the Regulations Enforcement Squad of the Federal Communications Commission drove us underground. When we put our heads together and thought about the best location for an underground radio station, we reached a consensus quite quickly: a cave. Unfortunately, we lived on the south shore of Long Island, which is essentially a large sandbar. There were no caves.

“Why do we have to live in a crummy place where there aren’t any caves?” asked Spike.

“Couldn’t we make a cave?” I asked, and as soon as I heard myself saying it, I wished I hadn’t. I realized that it sounded like the sort of thing I would say, the sort of thing I would want to do, and I regretted having spoken my mind so quickly, without subtlety, without any of the cunning gambits of persuasion that might have rallied my friends to the cause of cave-building.

“Making a cave,” said Matthew, “typically requires several thousand years, during which the geological conditions have to be just right. You need limestone and dripping water — ”

Spike gave him a poke.

“Ohhh,” said Matthew. “Now I see what you mean, Peter. You mean couldn’t we dig a shallow hole in the ground that we can just about crawl into and just about all fit into at once, where we can get sand in our hair, and sand in our shoes, and sand in our sandwiches, and — ”

“Great idea,” said Raskol.

“You said it,” said Marvin.

“I’m in,” said Spike.

“Okay, okay, me, too,” said Matthew.

So, we began, boldly, and without a plan. First, we dug a hole. I cannot recall the digging of the hole clearly, because whenever I try, my memory of my father’s digging a new cesspool overlaps my memory of the digging of the cave, like the overlapping signals of two radio stations that are close together on the dial.

My father hadn’t had much trouble rallying his friends to the cause of cesspool-digging. No cunning gambits were required, because our old cesspool had been overflowing for several days, creating a broad and malodorous puddle, the elimination of which must have offered a powerful incentive. They began digging on a Saturday morning, dug a hole that seemed enormous to me, lined it with cement blocks, capped it, and still had time for one last beer before the sun set.

From those men, I learned that a hole-digger has a highly developed sense of economy of labor. Almost from the start of their work, the men asked my father, often, with increasing frequency as the day wore on, “Is it deep enough yet?”

Marvin, Spike, Matthew, and Raskol and I kept asking one another the same question.

Leaning on his shovel, Raskol asked, “Is it deep enough yet?”

“Your head is still sticking up above the ground,” said Marvin. “We wouldn’t be able to stand up in there.”

“So, do we have to stand up in the thing?”

“That’s a good question,” said Spike. “Maybe we don’t have to stand up.”

“Sure we do,” said Marvin.

“We could sit down.”

“We wouldn’t all fit if we sat down,” said Marvin. “It’s not wide enough.”

“We could kneel,” said Spike.

“Kneel? Are you kidding? I’m not kneeling,” said Marvin. “We’ve got to be able to stand up. Anything else is humiliating, degrading. We’ll be huddled in a cave, bent and dirty. No, thank you. I won’t be bowed. I kneel to no one. I want to stand tall. A man’s cave is his castle.”

“Do you think the cavemen stood up in their caves?” asked Spike. “I don’t. Whenever you see pictures of them, they’re all kind of bent over.”

“Yeah, their knuckles drag on the ground,” said Raskol.

“They probably got that way because they couldn’t stand up in the caves,” said Marvin.

“I think that it will be a sorry state of affairs if after thousands of years of evolution we can’t stand up to our full height in a cave of our own making,” said Matthew.

“‘A cave of our own making,’” said Marvin. “That’s an interesting way to put it. I mean, we call this a cave, but when you get right down to it, it’s a hole — let’s face it — and can we say that we’ve made a hole? Or should we say that, in making a hill” — he indicated the pile of dirt beside him — “we left a hole behind?”

“I see what you mean,” I said. “A hole is the absence of something, and a hill is the presence of something, so — ”

“Yeah,” said Spike, “but in this case the hole is the motive for the work. We’re digging a hole, not building a hill.”

“True,” I said, “but the hill looks more like the motive. It shows. To most people, the hill is a hill but the hole is just — what’s left behind after making the hill — the not-hill — the anti-hill,” and to my surprise I found that when I said “most people,” I meant “me.”

[to be continued]

Subscribe to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy

Share The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy

Watch Well, What Now? This series of short videos continues The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy in the present.

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

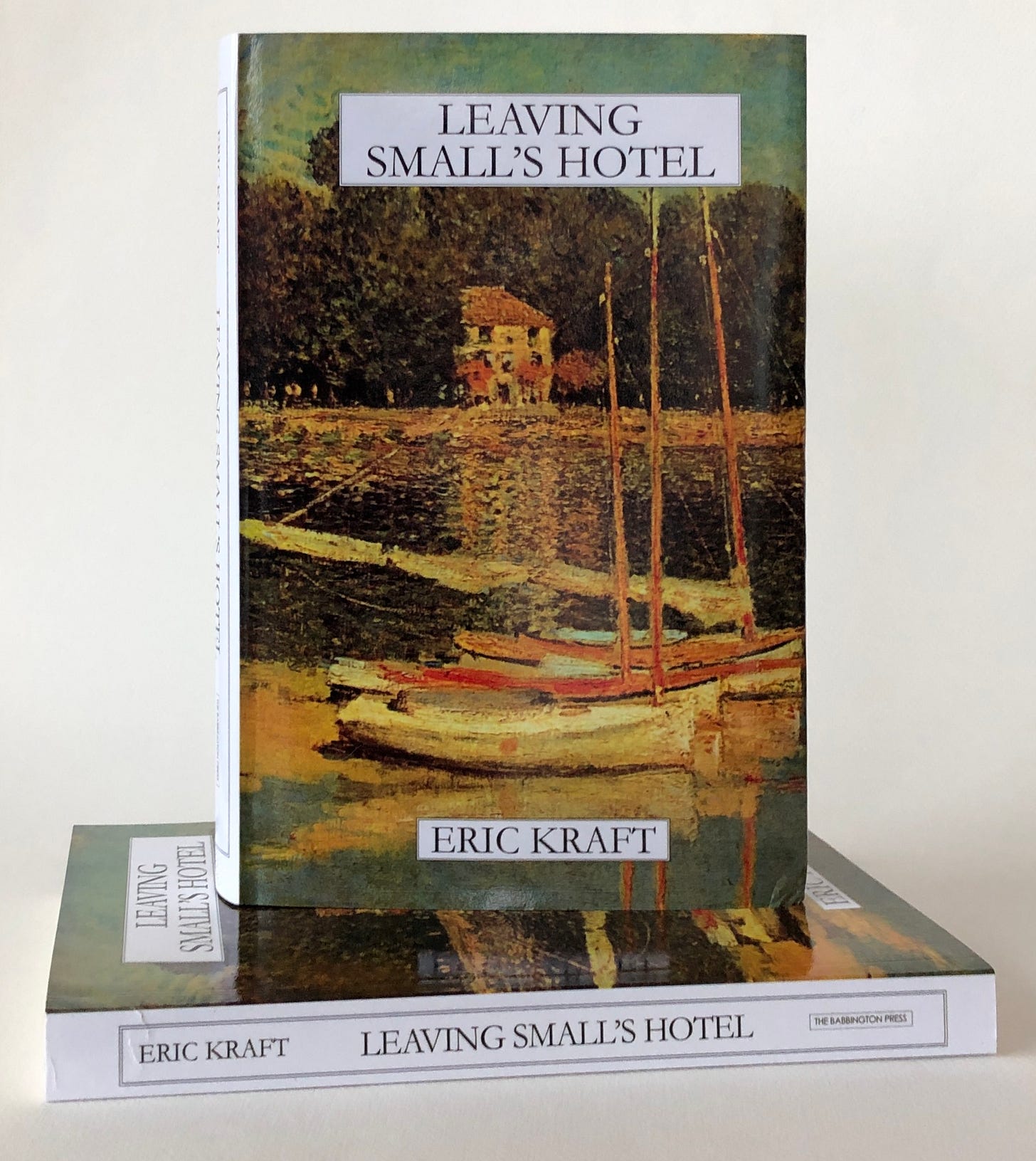

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide. The Substack serialization of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed. The Substack podcast reading of Little Follies begins here; Herb ’n’ Lorna begins here; Reservations Recommended begins here; Where Do You Stop? begins here; What a Piece of Work I Am begins here; At Home with the Glynns begins here; Leaving Small’s Hotel begins here.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies, Herb ’n’ Lorna, Reservations Recommended, Where Do You Stop?, What a Piece of Work I Am, and At Home with the Glynns.

You can buy hardcover and paperback editions of all the books at Lulu.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document), The Origin Story (here on substack), Between the Lines (a video, here on Substack), and at Encyclopedia.com.