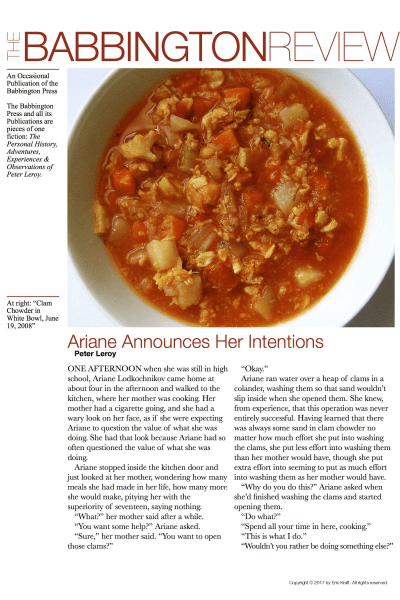

ONE AFTERNOON when she was still in high school, Ariane Lodkochnikov came home at about four in the afternoon and walked to the kitchen, where her mother was cooking. Her mother had a cigarette going, and she had a wary look on her face, as if she were expecting Ariane to question the value of what she was doing. She had that look because Ariane had so often questioned the value of what she was doing.

Ariane stopped inside the kitchen door and just looked at her mother, wondering how many meals she had made in her life, how many more she would make, pitying her with the superiority of seventeen, saying nothing.

“What?” her mother said after a while.

“You want some help?” Ariane asked.

“Sure,” her mother said. “You want to open those clams?”

“Okay.”

Ariane ran water over a heap of clams in a colander, washing them so that sand wouldn’t slip inside when she opened them. She knew, from experience, that this operation was never entirely successful. Having learned that there was always some sand in clam chowder no matter how much effort she put into washing the clams, she put less effort into washing them than her mother would have, though she put extra effort into seeming to put as much effort into washing them as her mother would have.

“Why do you do this?” Ariane asked when she’d finished washing the clams and started opening them.

“Do what?”

“Spend all your time in here, cooking.”

“This is what I do.”

“Wouldn’t you rather be doing something else?”

“Right now?”

“Yeah. Right now.”

“No. Did you wash the sand off those clams?”

“I washed them.”

“Let’s have them. I’m ready for them.”

“I’m not finished opening them.”

“Well come on. I’m ready for them.”

Ariane picked up the pace. When she’d finished, she passed her mother the bowl of clams in their liquor.

“What if you could be at a fancy restaurant in Paris, where somebody else is making the chowder? Wouldn’t you rather be served instead of cooking?”

“Sure. That would be great. I’d like that.”

“So you admit it. You get tired of cooking!”

“Of course I get tired of it.”

“But you keep doing it.”

“If I keep at it, someday I’ll get really good at it.”

“You’re already good at it.”

“I mean really good at it.”

Ariane’s mother stood there looking at her daughter, and then she said, “You don’t know what I mean by that, do you?”

“No.”

“Someday, I will make the best chowder I’ve ever made, the best I ever could make, maybe even the best that has ever been made.”

That seemed like such an absurd goal to set oneself that Ariane pitied her mother even more than she had earlier, when she was standing inside the kitchen door.

“Oh, Ma,” she said.

“Don’t laugh at me,” her mother said. “This is what I do.”

ABOUT TWENTY YEARS later, in the first edition of Making My Self — and Dinner, Ariane wrote:

My contempt for my mother took many forms. Pity was one of them. I don’t pity her now. I’ve accepted many of her ideas. If she were alive, I’d tell her so. I understand now that she had elevated motives for pursuing mundane goals. I understand now that the quotidian is an element of the eternal, that small steps make a journey. My mother was out to make a transcendent chowder, and she was willing to work at it day after day, making her tiny steps toward something sublime.

Following her example, I’m going to feed my soul with a project that fires my imagination, a project that is immense and eternal, or at least large enough to fill a lifetime. I’m taking up my mother’s project.

Making a chowder is enough, I now think, to allow for understanding the world and myself in it. However, to make the task a little more significant, or challenging, or worthy, I’m adding the making of a self, my self. I think that making a self will turn out to be a daily undertaking, like making the day’s dinner, but it will have a larger ultimate goal than the making of a day’s dinner, or even making the day’s dinner as well as it can be made—at least I assume that it will.

I think that some endeavors are baser than others and some are nobler than others.

Examples of baser endeavors are making a chowder to please a customer, or making a self to please a lover; “making” a chowder from a can, or making a self out of the ideas and attitudes that society sells like soap; making a chowder by sticking to a recipe, or making a self to match the requirements of a calcified system of beliefs.

Examples of nobler endeavors are making a chowder that is better than yesterday’s, or making a self who will find a way to make herself better tomorrow than she is today.

That is my motivation, my transcendent goal, my grand conception. Don’t laugh at me. This is what I’m going to do.

I need a starting point. It ought to be my mother’s recipe, but I don’t have that, so I’ve created a recipe by combining several published ones. It’s a pastiche of a recipe that makes a pretty good chowder. I’ll be developing it in the pages that follow.

2 ounces salt pork or 2 slices bacon

1/2 cup celery, sliced

1/4 cup carrots, sliced

2/3 cup onion, chopped

1 clove garlic

1 cup potatoes, peeled and cubed

2 cups water

2 cups fresh tomatoes, chopped

2 cups chopped hard shell chowder clams, Mercenaria mercenaria, with liquid

1/4 teaspoon thyme, oregano, basil, or rosemary

1 teaspoon parsley, minced

1/8 teaspoon cayenne pepper or red pepper flakes

1/4 teaspoon black pepper, freshly ground

salt to taste

Dice the salt pork or bacon.

Slice the celery, about a quarter-inch thick, on the bias.

Slice the carrots, a bit thinner than the celery, but at about the same angle.

Mince the garlic, finely.

Peel and cube the potatoes.

Chop the tomatoes.

Slowly fry the pork or bacon bits in a soup pot, dutch oven, or cauldron until the fat melts and the pork is crisp and golden. Remove the bits and set them aside.

Sauté the carrots until they begin to gleam. Add the celery and sauté until it, too, begins to shine. Add the onion and garlic and sauté until the onion begins to wilt.

Add the potatoes and water. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer for 10 minutes.

Add the tomatoes and simmer until the potatoes are done but still firm.

Shuck the clams, reserving their liquid.

Chop the clams. Add the clams and their liquid. Add the pork bits.

Add the herbs.

Add the cayenne pepper.

Simmer for three minutes.

Adjust seasoning, adding the salt and pepper

Serve. Savor. Revise recipe. Repeat.

In my memories of my mother, she is always cooking.

Ariane Lodkochnikov, Making My Self — and Dinner

Aim at an infinite, not at a special benefit. . . . then it will be a good always approached,—never touched; always giving health.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Method of Nature”

If you are what you eat, then you can become what you cook.

Ariane’s mother, quoted in Making My Self — and Dinner

Faites un dessin, recommencez-le, calquez-le; recommencez-le, et calquez-le encore.

Edgar Degas

The Babbington Press and all its publications are pieces of one fiction: The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy.

You can begin reading the Personal History at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future episode by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.