Chapter 4

Superior Indian Cookery

MATTHEW IS AT WORK, in his office, two floors from the top of a two-year-old building in the section of Boston that was once the garment district and is now the financial district, where construction has been booming for the last several years. At the former location of Manning & Rafter, the executive offices were actually within the factory. Now the factories are in Hong Kong, Korea, and Mexico, and Manning & Rafter doesn’t own them. The company has become a client of a contractor based in Hong Kong who delivers toys at a specified time, for a specified price, and farms the work out in a baffling international shuffle that meets his deadlines and maximizes his profits. When the last of the domestic manufacturing operation was eliminated and the factory became an echoing space, management moved into this tower, where there is no evidence of the manufacturing side of the business at all. By day, the building is full of executives and their clerical help; at night, vanloads of Haitian women arrive to clean it. Matthew’s office, it has occurred to him, faces the wrong way; the view extends beyond the harbor and the airport, out over the Atlantic, but he spends much of his day in telephonic conference with Hong Kong. When he first came to Manning & Rafter, he liked to spend part of each day mixing with the workers, watching the toys move along the line, finding out whether the workers’ children played with the toys they made, and if so what they thought of them. On his first trip to Korea to conduct an unnecessary inspection of the plant there, he asked all the questions he used to ask the men in Boston. The answers he got, filtered through translation, were cautious, polite, subservient, and useless. Now, on these inspection trips, he spends most of his time in meetings, in restaurants, or in his hotel. He used to be proud that he understood the technical aspects of production — materials, manufacturing methods, and so on — but now he sometimes doesn’t know what the new toys are made of until he reads the trade names for plastics on spreadsheets.

It’s one of those pellucid winter days that Boston gets in January, when details that usually go unnoticed shine crisp and bright, and ordinary things seem to flaunt themselves, demanding attention. On such days, the eye can see so much farther than usual that one’s context is enlarged. The world seems more complex, overwhelming, packed with things that demand attention, a daunting heap of tiny bits of information, like the mound of sand that Matthew was asked to try to comprehend as individual grains rather than a mound in a session at an executive retreat in the fall, in New Seabury, on the Cape. “See the grains,” said the session leader, “and you’re overwhelmed. See the mound, and you’re missing the details. Learn to switch between visions, and you control your perception of reality.” Matthew sat and listened and did the exercises. He did not take notes. He emerged from the session with a pounding headache. When it was time to write the required evaluation, he summoned BW for help:

Throughout the session, we had the feeling that the company had been bilked by a charlatan in a rumpled tweed jacket. In fact, we were convinced that the jacket, a disguise, a costume worn to meet our expectations of what a psychologist ought to wear, was proof that the charlatan was a charlatan, a crook in psychologist’s clothing. Upon emerging from the session, however, we were astonished to find that as a result of the training we had received in perceiving a mound of sand as individual grains, we were able to perceive the staggering fee the company had paid this tweedy fellow as individual dollar bills! Not a stack of bills, mind you, but individual bills. With just a little more effort, we were able to see the fee as a mound of quarters, and then as individual quarters. We are forced to admit that we really must have learned something. It may take a great deal of company time for practice, but we think that eventually we will be able to perceive the fee as individual pennies, and then we will know that each and every one of them was money well spent.

Nothing was ever said about this evaluation. Matthew has been surprised to find that, since the session, he tries the technique every now and then; he’s playing with it now, trying to grasp the view from his windows all at once, as a whole, and then shift to the details and try to perceive them all at once, and then shift back, and so on. When he gets the shifting to work, he can’t seem to stop himself. It’s dizzying, but he can’t stop. He seems to feel the building move.

The intercom on his desk burbles and ends the experiment, just as he is shifting from the whole to the details. “Yes?” Matthew says.

[to be continued]

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

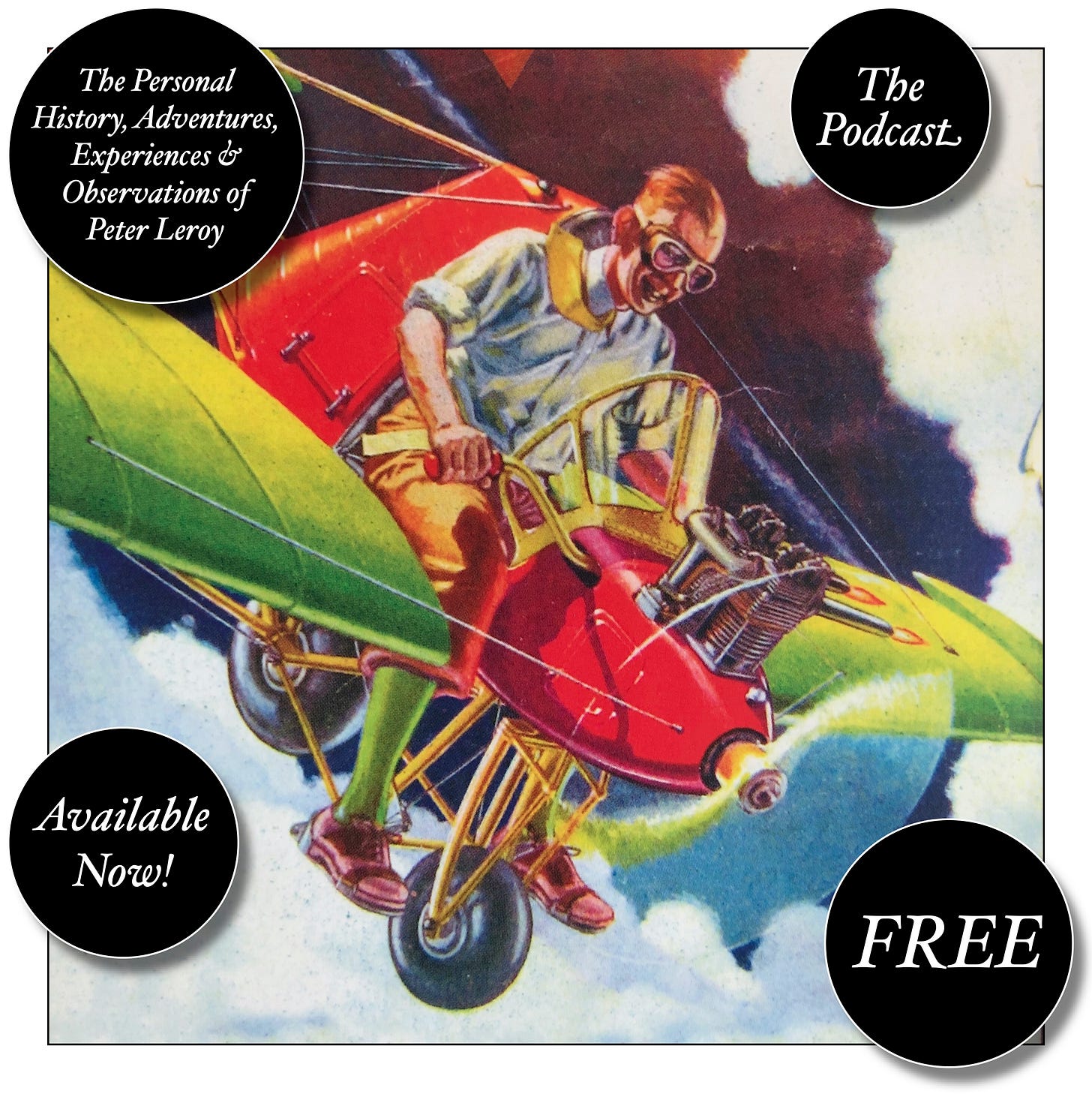

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can listen to “My Mother Takes a Tumble” and “Do Clams Bite?” complete and uninterrupted as audiobooks through YouTube.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of Little Follies and Herb ’n’ Lorna.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.