Ideas: Their Origin (Where do you get your . . .”)

“My goodness,” said May, “where do you get your ideas? …”

Herb ’n’ Lorna, Chapter 15

The video that opens this installment of the Topical Guide comes from Kraft’s presentation of the Persistence project at the Center for Fiction, November 10, 2011, at which Kraft announced in a handout to each member of the audience that when they made their way to the top floor, “All your questions will be answered, if they are among those that Kraft has prepared in advance.” [Kraft has asked me to thank Mary Spitzer for playing the “straight man” and asking the question that someone asks at nearly all of his readings. Thank you, Mary. MD]

Now, reader, please forgive me for quoting myself:

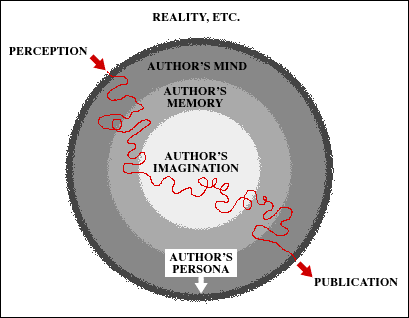

The following diagram illustrates in schematic form the situation of the author within the world and of the worlds within the author’s brain, including the author’s imagination. (Perhaps it is even a schematic diagram of the so-called author function.)

The area outside the outermost ring represents the ambient reality through which the author moves and from which he gets everything that he knows of everything there is; this is what Emerson called “the actual world—the painful kingdom of time and place—[where] dwell care, and canker, and fear.”

The first ring is the author’s persona, a thin protective shell around the author within. Notice, however that the ring of the persona is gray and fuzzy, as are all the areas in the diagram. These qualities in the schematic, grayness and fuzziness, are meant to indicate (1) permeability, the fact that information can pass through an area (in both directions) and (2) imprecision, the fact that the boundaries of the regions are ill-defined, not sharp and precise. So, the persona is a kind of semipermeable membrane, through which information about the real world can pass into the region of the author and through which the products of the author can pass into the real world.

The region within the edge of the outer shell is the totality of the person who contains an author, un autre. The region within the author’s ring is the region of the author—but remember that in the case of a region with fuzzy edges we have a difficult time saying where, exactly, the edge of the region is, where the region stops. Remember also, please, that Author Kraft is a creation of Total Kraft’s, or if you like, a character in a work of Total Kraft’s, as is Persona Kraft; now, if we consider that Total Kraft includes Author Kraft and Persona Kraft, then we must take the creation of the totality of Kraft to be a work of Total Kraft’s, too: a kind of fiction, as, of course, it is, but if we pursue that line we’ll go on pursuing it and pursing it without ever getting to the end of it, and we’ll all get really splitting headaches, so let’s return to the characters who appear on printed pages, or more broadly considered, characters manifested through words, and confine ourselves to them.

To answer a question asked of all authors: yes, all of those characters (including, of course, me) have their origins in the region outside the author, in the real world.

I mean what I said and only what I said, that we all have our origins there, but I do not mean that we all have relatives out there, bundles of accident and incoherence who are wondering what’s for breakfast, and I do not even mean that we all necessarily originate from people out there. Some of us have arisen from other things: a melody that suggested a singer; moonlight that seemed to call for a pair of lovers; or even a vacancy toward which people seemed to turn, a vacancy that implied a missing someone. Now that I have qualified it, I will repeat it: all of us originated outside. Each of us began as a perception; that is, something from the region outside that was taken in to the region of the author. (I employ the passive voice here because so many perceptions are accidental, unwilled. For example, just a few days ago, while I was enjoying a rare hour of relaxation, lying in the sun on a chaise longue, reading Anthony Trollope's The Small House at Allington, I was, apparently, bitten by some insect of which I was at the time unaware, but which seems to have injected me with a toxin to which I have had an allergic reaction, leaving my right side and an area of my lower back just above my right buttock covered with red welts that are sore enough to make sleeping uncomfortable, giving rise, as you might expect, to uneasy dreams.)

So, we all began as perceptions, but all perceptions are misperceptions, because (a) our senses simplify and distort what we perceive, (b) an instant later, the intellect has further distorted and simplified the already simplified and distorted perception and categorized it and filed it for reference in the memory, so that it is now (c) only a recollection of a perception, a shadow of its former self, and by some mysterious process still poorly understood despite the best efforts of students of consciousness, these memories begin an apparently inevitable drift toward the region of the imagination, where they are massaged and amplified and bent and twisted until they are scarcely recognizable as the offspring of the bits of the outside world that gave rise to them. Thus, Scrooge’s undigested bit of mutton becomes the Ghost of Christmas Past, and thus there are no immediate experiences, and thus there are no characters drawn directly from life. We are, each of us, born, or made, somewhere along the path from the real world to the region of the imagination.

Our imagination, and our dreams, are forever invading our memories; and since we are all apt to believe in the reality of our fantasies, we end up transforming our lies into truths. Of course, fantasy and reality are equally personal, and equally felt, so their confusion is a matter of only relative importance. . . . I am the sum of my errors and doubts as well as my certainties.

Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh (his autobiography, translated by Abigail Israel)

See also:

“Inspiration” TG 125; and Transformation TG 78; Imagination TG 62; Imagination, Improvisation TG 102; Imagination TG 113

Have you missed an episode or two or several?

You can begin reading at the beginning or you can catch up by visiting the archive or consulting the index to the Topical Guide.

You can listen to the episodes on the Personal History podcast. Begin at the beginning or scroll through the episodes to find what you’ve missed.

You can ensure that you never miss a future issue by getting a free subscription. (You can help support the work by choosing a paid subscription instead.)

At Apple Books you can download free eBooks of “My Mother Takes a Tumble,” “Do Clams Bite?,” “Life on the Bolotomy,” “The Static of the Spheres,” “The Fox and the Clam,” “The Girl with the White Fur Muff,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Call Me Larry,” and “The Young Tars,” the nine novellas in Little Follies, and Little Follies itself, which will give you all the novellas in one handy package.

You’ll find overviews of the entire work in An Introduction to The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of Peter Leroy (a pdf document) and at Encyclopedia.com.

Share this post